#107: Surviving Hurricane Hugo, a Textile Tour, and the Combahee River Raid

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles and upcoming SC historical events.

Dear reader,

Welcome to SC History Newsletter #107!

As we continue into summer, this week I began to think a lot about hurricanes and summer/early fall weather patterns. I decided to write about Hurricane Hugo (struck South Carolina on September 22, 1989) and the indelible mark it left on the state. Not only did I want to include facts and figures about the damage the hurricane caused, but I also wanted to include stories of the people who lived through the horror of the storm.

Did you experience Hurricane Hugo in South Carolina? If so, please reply to this email. I’d love to hear about your experience.

Another quick note: y’all know my emails can get pretty long. :) In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

As always, I’d like to welcome the following new subscribers to our community. Thank you for your interest in South Carolina history!

kksearer.6162

dfkendall

rhonddt

connortapp

wbeacham

rdneighbors0

lpecoraro

dbmanning1155

jturnage

jmccormick

wesemory

blauchshop

New friends! If you are new to the newsletter, please note that there are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and so much more! I encourage you to take a look at our archive here.

Send me your topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you. :)

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Events

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered.

Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email, send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com, or use the button below to send me your events.

Event Recommendation of the Week:

Thursday, August 15th at 6:00 pm | “Exclusive Storeroom Tour: A Behind the Scenes Look at 19th & Early 20th Century Textiles at the Charleston Museum” | The Charleston Museum | Charleston, SC | $40 Members, $55 Non-Members

“Join Curator of Historic Textiles Virginia Theerman for an exclusive preview tour of the objects going into the new permanent exhibit: Beyond the Ashes: The Lowcountry’s New Beginnings. Go behind the scenes in the Museum’s storeroom and get an up-close look at late 19th and early 20th century textiles currently not on view to the public. Learn about the major events that shaped Charleston’s past century as a city. Theerman will also discuss what it takes to prepare objects for permanent exhibition, and how to plan ahead for years to come. Cool down on a hot summer evening in the temperature-controlled storeroom for this special, rarely offered, curator-led tour!

Enjoy light refreshments starting at 5:30 pm before the tour commences.”

➳ SC History Book & Article Recommendations

“COMBEE: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom during the Civil War” (Published February 2024)

(Note from Kate: This is the book I’m currently reading and it’s about 400 pages (woo!) so I won’t have it finished for a bit, but wanted to share the publisher’s description about it below as I find this topic so fascinating and important in South Carolina’s history.)

“The story of the Combahee River Raid, one of Harriet Tubman's most extraordinary accomplishments, based on original documents and written by a descendant of one of the participants.

Publishers Weekly Starred Review

Library Journal Starred Review

Booklist Top Ten History Books of 2024

Most Americans know of Harriet Tubman's legendary life: escaping enslavement in 1849, she led more than 60 others out of bondage via the Underground Railroad, gave instructions on getting to freedom to scores more, and went on to live a lifetime fighting for change. Yet the many biographies, children's books, and films about Tubman omit a crucial chapter: during the Civil War, hired by the Union Army, she ventured into the heart of slave territory — Beaufort, South Carolina — to live, work, and gather intelligence for a daring raid up the Combahee River to attack the major plantations of Rice Country, the breadbasket of the Confederacy.

Edda L. Fields-Black — herself a descendent of one of the participants in the raid — shows how Tubman commanded a ring of spies, scouts, and pilots and participated in military expeditions behind Confederate lines. On June 2, 1863, Tubman and her crew piloted two regiments of Black US Army soldiers, the Second South Carolina Volunteers, and their white commanders up coastal South Carolina's Combahee River in three gunboats. In a matter of hours, they torched eight rice plantations and liberated 730 people, people whose Lowcountry Creole language and culture Tubman could not even understand. Black men who had liberated themselves from bondage on South Carolina's Sea Island cotton plantations after the Battle of Port Royal in November 1861 enlisted in the Second South Carolina Volunteers and risked their lives in the effort.

Using previous unexamined documents, including Tubman's US Civil War Pension File, bills of sale, wills, marriage settlements, and estate papers from planters' families, Fields-Black brings to life intergenerational, extended enslaved families, neighbors, praise-house members, and sweethearts forced to work in South Carolina's deadly tidal rice swamps, sold, and separated during the antebellum period. When Tubman and the gunboats arrived and blew their steam whistles, many of those people clambered aboard, sailed to freedom, and were eventually reunited with their families. The able-bodied Black men freed in the Combahee River Raid enlisted in the Second South Carolina Volunteers and fought behind Confederate lines for the freedom of others still enslaved not just in South Carolina but Georgia and Florida.

After the war, many returned to the same rice plantations from which they had escaped, purchased land, married, and buried each other. These formerly enslaved peoples on the Sea Island indigo and cotton plantations, together with those in the semi-urban port cities of Charleston, Beaufort, and Savannah, and on rice plantations in the coastal plains, created the distinctly American Gullah Geechee dialect, culture, and identity--perhaps the most significant legacy of Harriet Tubman's Combahee River Raid.”

Do you have a book or article on South Carolina history that has caught your attention? Reply to this email or submit here! We would love to highlight.

➳ SC History Topic of the Week:

Considered one of, if not the, most devastating storm in South Carolina’s history, did you know that 264,000 people evacuated their homes in 8 counties to escape Hurricane Hugo (1989)?

There have been many devastating hurricanes in South Carolina’s history — such as Hurricane Hazel (1954), Hurricane Gracie (1959), Hurricane Matthew (2016), and Hurricane Florence (2018) — but Hurricane Hugo (1989) is considered by many to be the “worst hurricane strike of the 20th century” in South Carolina.

How does a hurricane begin? In Hugo’s case, the combination of warm ocean waters, favorable atmospheric conditions, and low wind shear (a condition in the atmosphere where there is minimal variation in wind speed) contributed to Hugo's rapid intensification and strength as it approached the southeastern United States.

Here is how the hurricane progressed:

Origin as a Tropical Wave (September 9, 1989): A tropical wave emerged off the west coast of Africa and began to move westward across the Atlantic Ocean. A tropical wave is a type of “atmospheric trough, an elongated area of relatively low air pressure, oriented north to south, which moves from east to west across the tropics, causing areas of cloudiness and thunderstorms.”

Development into a Tropical Depression (September 10, 1989): The wave showed increased “organization and convection,” leading to the formation of a tropical depression east of the Lesser Antilles.

Upgrade to Tropical Storm Hugo (September 11, 1989): The system continued to strengthen, and the National Hurricane Center (NHC) upgraded it to Tropical Storm Hugo as it moved west-northwestward.

Intensification to a Hurricane (September 13, 1989): Hugo rapidly intensified into a Category 1 hurricane. This intensification was driven by favorable conditions, including warm sea surface temperatures and low wind shear.

Major Hurricane Status (September 15-17, 1989): Hugo underwent rapid intensification, reaching Category 4 status. At its peak, it achieved Category 5 intensity with “sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 918 mb.”

Impact on the Caribbean (September 17-18, 1989): Hugo first impacted the Lesser Antilles, causing extensive damage in Guadeloupe, Montserrat, and other islands. It then moved across the northeastern Caribbean, affecting Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Path Towards the U.S. Mainland (September 18-21, 1989): After moving through the Caribbean, Hugo weakened slightly but remained a powerful hurricane as it moved northwestward towards the southeastern United States.

Landfall in South Carolina (September 22, 1989): Hugo made landfall just north of Charleston, South Carolina, as a Category 4 hurricane with sustained winds of 140 mph (225 km/h).

On September 20th, 1989 — 2 days before landfall — officials in Charleston County recommended that residents evacuate. Local governments disseminated the order, assisted by the National Guard.

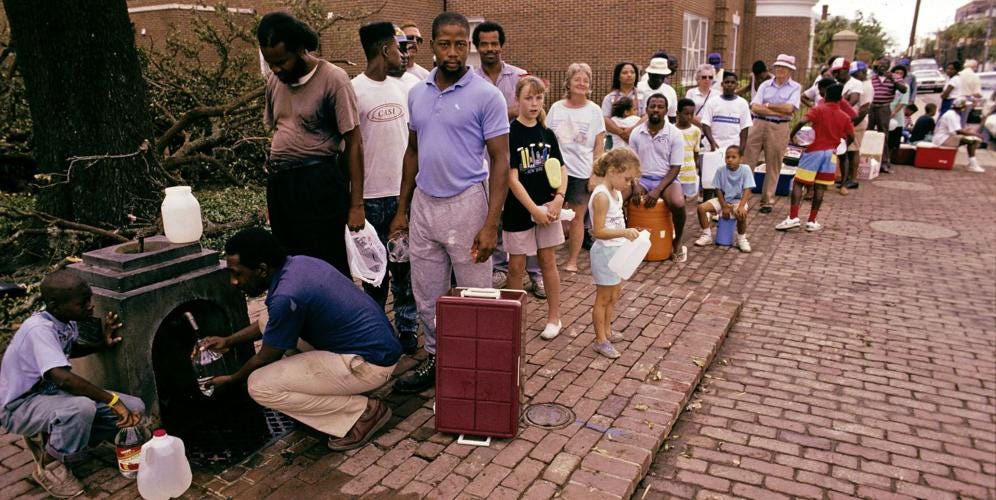

Approximately 264,000 people were evacuated before the hurricane struck, primarily from the coastal regions of South Carolina and North Carolina. The evacuations were coordinated by state and local authorities, as well as federal agencies, to ensure the safety of residents in the storm's projected path. Most took shelter in the homes of friends or relatives, and relatively few sought refuge in public shelters. A fifth of evacuees took refuge within 30 minutes of their homes.

The large-scale evacuation was one of the most significant in the history of the southeastern United States and played a crucial role in minimizing the loss of life and injuries from the hurricane.

Though as we will see in the stories below, not everyone was able to evacuate.

On September 22, 1989, Hurricane Hugo made landfall in South Carolina. The eye of the Category 4 hurricane was 30 nautical miles wide, with storm surge flooding 15-20 feet above normal. Hugo cut a path through the state just north of Charleston and continued inland to Lake Moultrie and west of Sumter, through Chester and York counties and by 5 am, was in the area of Charlotte, N.C.

On the 25th anniversary of Hurricane Hugo, Colleton County, SC created a report that described the storm’s damage:

“The primary coastal damage was caused by storm surge flooding, surge-related erosion, wave action and high winds with rainfall. Inland counties also received unexpected high winds and torrential rains. Falling trees and high winds broke power lines, crushed cars, and blocked roads while also breaking windows, peeling roofs, destroying mobile homes and causing widespread damages to homes and buildings. Many areas lost utilities for up to two weeks. Despite conditions, only two tornadoes were confirmed: a small tornado apparently developed in western Sumter County and another one near Kershaw in Lancaster County.”

The scope of Hugo’s destruction was as immense as the storm itself. Not only was the entire coastal region damaged from Edisto Island up to Myrtle Beach, the hurricane-force winds reached inland all the way to North Carolina.

Meteorologists estimate that “some 3,000 tornadoes were spawned as Hugo ripped a swath of destruction” through the state. Twenty-nine of South Carolina’s 46 counties were declared disaster areas.

In its wake, Hugo left:

13 directly related deaths, 22 indirect deaths, and several hundred injuries

$6.5 billion in damages

80% of South Carolina without power

264,000 evacuated from their homes in eight counties

270,000 temporarily unemployed

60,000 left homeless

54,000 state residents seeking disaster assistance

Other response actions required because of Hugo were:

The Red Cross opened 191 shelters that housed 89,968 people at the height of the evacuation. Red Cross workers provided mass feeding in shelters and on mobile feeding routes for 30 days.

$62 million in food stamps were issued to more than 200,000 households

An initial effort to rebuild dunes cost the state and federal governments $3.8 million.

More than 3,000 active-duty service members were employed in support and execution of assigned tasks.

30 assistance centers were established to receive applications for loans, grants, housing and other types of needs.

The forest communities lost more than 6.7 billion board feet in timber valued at $1.04 billion. The damaged timber, concentrated on 4.5 million acres, represented 36 percent of the state’s woodlands.

Primary and secondary schools received $55.6 million in damages. Crop damages topped $2 billion.

While the numbers speak to the devastation of Hurricane Hugo, it’s the stories of the people who survived the storm that bring to life the horror of the event itself.

A man named Thomas Williams from McClennanville, SC was interviewed in Mount Pleasant Magazine in 2021 and shared this terrifying account of his family’s experience during Hurricane Hugo:

“The dog is normally pretty quiet…but that night he just wouldn’t shut up. My wife told me to let him inside because he was scared. Well I did, but he still wouldn’t stop whining. I was fixing to put him back out when the wind started howling again, this time with a vengeance.

I heard a cracking noise from the back of the house and saw part of the roof come off. I didn’t want the clothes in the back bedroom to get wet so I immediately started over there. As I walked down the hallway I could feel the carpet rising up around my feet. At first I thought that the wind was blowing so strongly it was lifting the carpet. Then I saw the water coming up through the floor and I knew we were in trouble…

I knew we were trapped inside the house so I told everyone to head for the kitchen because that was where the access door to the attic was. By then it was too late. The kitchen had about three feet of water in it and the appliances and counters were either toppled over or floating around. There was no way we could climb over all those things and get to the door. Besides, I couldn’t even find the ladder that was in the kitchen.

I rushed everyone into the kid’s bedroom because there was a huge dresser in that room we could all stand on. That was when I decided to bust a hole in the ceiling to get into the attic. The ceiling in that room was sheet rock over plaster and I had a devil of a time busting through. I pounded and pounded, and just as I put a hole in the ceiling, the water lifted that dresser up like it was a cork. We were all tossed into the water which was about three feet high at the time. We fished everyone out and they seemed to be okay but at that point I didn’t know what to do. We had nothing to stand on and the water was rising fast.

Just then my daughter said, ‘Daddy, look! There’s the ladder.’ Sure enough, like a gift from God, here came the ladder floating into the bedroom. I don’t know how it got out of the kitchen but it definitely saved our lives. I stood it up under the hole and began carrying the children up to the attic. It was pitch black in there and I told them to stay on the main beam and not to move. I knew if they stepped onto the sheet rock they would come right through the ceiling.”

After my wife climbed into the attic I started throwing everything that was usable up there — clothes, food, flashlight, candles. The cooler floated by and I threw that up there, too. By then, the water was about five feet high so I grabbed the dog off the bunk bed and we climbed into the attic. All of this happened in a time span of no more than 10 to 15 minutes from when I first saw the water in the kitchen…

When I looked down into the bedroom, it was as if someone had turned a light on. I could see that room just as clear as daylight, even down to the pictures on the wall. I saw a bag of shrimp float out of the room and I remember saying to my wife, ‘There go the shrimp, trying to get back to the ocean.’ To this day I can’t understand where that light came from but it was a real comfort to be able to see something from the darkness of the attic.”

We couldn’t find the flashlight but we managed to locate a candle. My wife had a fairly dry pack of matches in her coat pocket and she tried to strike one but it didn’t light. Thank God it didn’t because I suddenly realized there was a very strong smell of gas in the attic. We had a large propane tank outside, and one of the lines in the kitchen must have broken. I suppose that the water, which by this time was almost up to the top of the doorways, was pushing the gas into the attic. I knew we had to get out of there and into some fresh air so I made everyone crawl along the main beam toward the kitchen where part of the roof had blown off…

The constant pounding and howling of the wind almost drove us crazy. The rain pelted us like beebees and we had to dodge large objects that were flying by. I just kept saying, ‘Lord, won’t you please stop the wind.’

I could see the waves of water outside and some of them were rolling over the backboard of our basketball pole. Then I heard screams from Lincoln High School. The school was about 300 yards from my house and the wind was roaring around us but we could still hear people screaming. I thought, ‘My God, if they can’t survive in there, how are we hoping to make it out here?’

“Some of the waves were reaching up to our roof and I was afraid that one of them might wash us out of the attic. Then I said to myself, ‘If that happens, which one of my children am I going to save and which ones will I let drown?’ So I grabbed the telephone cord and used it to tie us all together. I told them that it would keep anyone from floating away. In my own mind I decided that this way we would at least live together or die together.”

25 years after Hurricane Hugo, in 2014, Charleston Magazine put together an article of stories of other survivors. Johnny Cleary from Awendaw recounted that he was with his family at their farm at Buck Hall when he realized the house might not hold:

“We felt like the three little pigs, running from the straw house to a stronger one…The wind was insane. The ditch between the properties was being flooded by the surge and looked like rapids. I still can’t believe we made it. The next day it looked like a bomb had hit. We could see for miles to the horizon because the trees had either been cut in half like broken matchsticks or were gone completely. In fact, 1.3 million acres of forest had been destroyed—enough timber to build 660,000 new homes.”

In Thomas Williams’ first account above, he mentions hearing screams from the local Lincoln High School in McClennanville, SC that was 300 meters away from his house. The Charleston Magazine article reported first-hand accounts of the people who were within the school:

“That none of the some 600 people who spent the night of September 21st at Lincoln High were killed is one of Hugo’s miracles. Then-principal Jennings Austin was at the school during Hugo and recalls that people began settling in around 4 p.m.: ‘We weren’t real concerned at first. Even when the power went out around 9 p.m., leaving us in the spooky emergency lighting, it wasn’t so bad. We could hear the wind howling outside but the building was built as solid as a rock. We hoped that we might get through the night without incident.’

Around midnight, Austin was with deputy sheriff Charlie Dutart making a check of the school’s L-shaped building. Most of the people were in the cafeteria/auditorium at the end of one of two long halls. Austin and Dutart were at the far end of the other hall when water began seeping in. ‘When we first realized water was coming in, it was only up to our ankles,’ he recalls. ‘In what seemed an instant, the water was up to our knees, then to our waists. Apparently it was pouring into the classrooms where the pressure had broken out the air-conditioning units. There was no way to get back to the cafeteria. If we were going to live, we needed to find a way out.’

Going into a classroom, the men grabbed an overhead projector from a table and tried to break the Plexiglas window. It wouldn’t budge. After repeated attempts, the window finally broke. At this point, the water was chest-deep.

The men pushed outside into a raging chaos and started climbing up the building, away from the rising surge and onto the roof, only to be slammed down by the powerful winds. They ended up crawling on their bellies, barely sheltered by the two-foot-high wall bordering the roof, until they reached the higher cafeteria roof, where they laid down amidst some pipes. At one point, Austin says that he saw an entire brick house float by, carried by the swirling waters of the surge. ‘We could hear the screams of the people below us,’ he says. ‘We were sure that if we were lucky enough to live through the night, we’d find 600 dead bodies in the cafeteria, drowned.’

In fact, those in the cafeteria were fighting a watery hell in darkness, doing everything possible to keep their heads above the rising waters. They frantically placed tables on tables, chairs on tables, finally crowding onto the stage area, where they repeated the stacking of tables and chairs and climbed atop, holding their babies and children overhead.

His group of 10 to 15 people consisted of women, children, and a few men. “I noticed a nearby woman trying to hold up two children,” he wrote. “I took one and held her above the water. She was a three-year-old named Tsara.... We stayed in chest-high water for several hours. I remember talking and singing to the child, trying to pass time.” Later, around 3 a.m., someone on the roof knocked out a top windowpane on the opposite wall. Only a few dared cross to safety. ‘I knew the women couldn’t swim across the cafeteria, and I knew I could not swim the distance with a three-year-old in tow, so I prayed along with everyone else,’ remembers Metts. Finally at about four or five that morning, the water level lowered. Miraculously, no one in the cafeteria was seriously injured.

At first light, people began coming out of the school, and Austin and the men were able to climb off the roof. ‘It was joyous,’ recalls Austin. ‘Everybody was hugging, grinning, even laughing. We were alive. We were standing in waist-deep water, but we had survived. What saved everybody inside the school were the new Plexiglas windows. They buckled with the stress of water pressure but held. Otherwise, water would have poured in and completely inundated the interior of the school.’

Hurricane Hugo left severe damage in its wake, and the recovery process for the affected South Carolina communities took months, and in certain cases, years.

The immediate aftermath saw significant efforts focused on restoring basic services and infrastructure. Power and water services were restored within weeks to months, depending on the area. Full economic and community recovery, however, took much longer.

Many areas, especially those that were hit hardest like Charleston and rural communities, took several years to fully recover. Homes, businesses, and infrastructure needed to be rebuilt. Communities also focused on rebuilding their tourism industries, restoring ecosystems, and implementing improved building codes and preparedness measures.

On September 29, 1989, then President George H. W. Bush toured the damage caused by Hurricane Hugo in Charleston. Here are some excerpts from his remarks:

“Even though the trip was short, I had a chance to talk to some of the people, and I commend the spirit of the people of South Carolina. I expect it's true for North Carolina and Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. But you couldn't help be impressed to hear the people saying look, we're going to bounce back.

One thing that touched me very much was a young homeowner there saying that he had had offers of help from all over this country. And I think it does bring out the very best in the men and women of America who want to help in a tragedy of this nature. It's tough, it was devastating, but the spirit of South Carolina came through loud and clear. And so, we'll be alert to do what additionally we might do. But I'm proud of those Federal workers and those civilians that are out there doing their level best to snap back after a terrible tragedy.”

In its aftermath, Hurricane Hugo highlighted the need for stronger building codes, better emergency preparedness and response plans, and improved public awareness and education about hurricane risks.

Reports such as “Learning from Hurrican Hugo: Implications For Public Policy” (1992) were prepared by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), The National Committee on Property Insurance (NCPI), and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and analyzed the storm’s effects — from biological systems, performance of structures, psychological effects of the storm on humans and human systems, emergency management, and much more. In the report’s section on the psychological effects of the storm on the population, the report stated:

“Few victims of Hugo sought individualized psychiatric services from licensed professionals; rather, the entire impact area became a mass group psychotherapy marathon that lasted for months. Repeated discussion of the event and reliving the emotional trauma in almost any social encounter helped people master their anxiety and depression without individualized professional intervention (Austin 1991).”

Since Hurricane Hugo in 1989, South Carolina has made significant advancements in emergency preparedness. Some key developments include:

Improved Forecasting and Warning Systems: Advances in meteorology and technology have led to more accurate weather forecasting and earlier warnings. The National Weather Service and local agencies now use sophisticated models to predict hurricanes and other severe weather events.

Enhanced Evacuation Plans: South Carolina has developed more effective evacuation strategies, including better traffic management, more organized sheltering options, and improved communication with the public.

Stronger Building Codes: Building codes in South Carolina have been updated to include more stringent requirements for wind resistance and flood protection, reducing the risk of damage from hurricanes and other natural disasters.

Increased Community Resilience Programs: There are now more community-based programs aimed at increasing resilience, such as neighborhood preparedness initiatives, emergency response training, and public awareness campaigns.

Better Coordination and Training: Emergency management agencies have improved coordination with local, state, and federal entities. Regular training and exercises are conducted to ensure that all parties are prepared to respond effectively.

Upgraded Infrastructure: Investments have been made in infrastructure to better withstand storms, including improvements to drainage systems, seawalls, and flood barriers.

Public Education and Outreach: There is a greater emphasis on educating the public about emergency preparedness, including guidance on creating emergency kits, developing family plans, and understanding evacuation procedures.

Technological Advancements: The use of technology, such as mobile apps for emergency alerts and real-time updates, has enhanced communication and information dissemination during crises.

An FYI for us all: according to the SC Department of Natural Resources, the official Atlantic Hurricane Season begins each year on June 1st and ends on November 30th. Hurricane Preparedness Month is now each May in South Carolina.

Did you experience Hurricane Hugo or have a relative who did? We would love to hear your story. Leave a comment below!

➳ SC History Quote of the Week

"On this day twenty years ago, South Carolina weathered a storm that forever changed our state. Even after two decades, the legacy and memory of Hurricane Hugo remains. After the storm passed, the people of the Palmetto State awoke to the sight of downed trees, bridges and demolished homes and buildings. Beneath the rubble, South Carolinians also found a sense of community and a desire to rebuild our coast in the wake of the storm. The days leading up to Hurricane Hugo’s landfall were distressing for all South Carolinians who remember it, but we believe that we emerged from the storm a much stronger state. The experience underscored the critical value of early evacuation, bold leadership, and personal and regional preparation. Preparation and quick response is critical to ensuring the safety of everyone, and we sincerely hope that all Americans will learn from the tragedy of Hurricane Hugo on September 22, 1989.”

—On September 22, 2009, United States Senator Lindsey Graham (R-South Carolina)and Congressman Henry Brown (R-South Carolina) released this statement on the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Hugo.

➳ “Hurricane Hugo” Article Sources

Charleston Magazine. "Remembering Hugo 25 Years Later." Charleston Magazine, n.d.,https://charlestonmag.com/features/remembering_hugo_25_years_later#:~:text=Hurricane%20Hugo%20left%20us%20stunned,Water%20was%20undrinkable. Accessed 28 July 2024.

Colleton County. "Hugo 25 Fact Sheet." Colleton County, n.d., chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.colletoncounty.org/sites/default/files/uploads/epd/hugo25-fact-sheet.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2024.

Federal Emergency Management Agency. Learning from Hurricane Hugo: Implications for Public Policy. Washington, D.C., June 1992, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://coast.noaa.gov/data/hes/docs/general_info/LEARNING%20FROM%20HURRICANE%20HUGO%20IMPLICATIONS%20FOR%20PUBLIC%20POLICY.pdf. Accessed 28 July 2024.

Graham, Lindsey. "Senator Graham Remembers Hurricane Hugo on 30th Anniversary of Landfall." Office of Senator Lindsey Graham, 21 Sept. 2019, https://www.lgraham.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=E3A366F2-802A-23AD-4BD8-976B61F6F402. Accessed 28 July 2024.

Mount Pleasant Magazine. "Nightmare in McClellanville: Remembering Hugo in 1989." Mount Pleasant Magazine, 2021, https://mountpleasantmagazine.com/2021/remembering/nightmare-in-mcclellanville-remembering-hugo-in-1989/. Accessed 28 July 2024.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. "Chapter 12: Lessons from Hurricane Hugo." The Impacts of Natural Disasters, 1993, pp. 203-219, https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/1993/chapter/12. Accessed 28 July 2024.

National Weather Service. "Tropical Definitions." National Weather Service, n.d., https://www.weather.gov/mob/tropical_definitions. Accessed 28 July 2024.

South Carolina State Climatology Office. "Hurricane Hugo." South Carolina State Climatology Office, n.d., https://hurricane.sc/. Accessed 28 July 2024.

WMBF News. "This Day in History: 33 Years Ago, Hurricane Hugo Devastated South Carolina." WMBF News, 22 Sept. 2022, https://www.wmbfnews.com/2022/09/22/this-day-history-33-years-ago-hurricane-hugo-devastated-south-carolina/. Accessed 28 July 2024.

WIS News 10. "Hurricane Season: A Look Back at South Carolina’s Most Devastating Hurricanes." WIS News 10, 2 June 2023, https://www.wistv.com/2023/06/02/hurricane-season-look-back-south-carolinas-most-devastating-hurricanes/. Accessed 28 July 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!