#60: The Burning of Columbia, Emma LeConte's diary, and archaeological findings at USC

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #60 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

Here’s a little welcome/update audio message:

In our SC History Fun Facts section, I typically write on 2 SC History subjects. Today, I decided to tackle a huge subject: The Burning of Columbia. In the course of writing the newsletter today, it struck me that this topic is too big and too important, and that it didn’t feel right to have a second historical topic in the newsletter today. The topic needed its own space to breathe. So I have only published on one topic today, and it is very tragic — but we will dive in together. Note that there might be other “heavier” topics in the future where this might apply as well. I mentioned a few newsletters ago that I hadn’t really delved into the Civil War yet because I knew it was going to be very intense. With today’s newsletter, I think I am ready to begin focusing on this important history.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new free subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

ryan3220

georgermims

osbornemargaret204

rick5097

hmogden

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Wednesday, April 17th at 4:00 pm | “University of South Carolina Archaeology Exhibit” | University of South Carolina | Columbia, SC | FREE

“Come check out what some South Carolina Honors College students have been doing on the Horseshoe! An Honors College class is excavating the Horseshoe to raise awareness of the enslaved labor force that built the university. This is the first time in 51 years that archaeological research is being done at the heart of campus. Students in “Digging through the past: Exploring the Archaeological Resources of USC” work around three different mapped sites: the old president’s house that was demolished in 1939, enslaved quarters and an observatory. The event includes remarks from the students, a showcase of finds, and an open excavation unit in front of McKissick for visitors to see.”

➳ SC History

I.

Today we discuss the events leading to the Burning of Columbia,

Listen to this section in the mini audio voiceover below!

In 1865, Columbia was small for a capital town. The 1860 census showed only 8,052 residents, some 3,500 whom were slaves (43% of the population was enslaved). By comparison, Charleston had 40,522 residents in 1860, almost 5x the population of Columbia.

The aging wooden statehouse of South Carolina had been recently moved and was in the process of being replaced by a granite one. In 1865, the structure “lay unfinished, much like the Capitol dome in Washington, D.C., at the time.”

The Columbia economy “was based around the cotton trade, and many warehouses were dedicated to its storage.”

The South had overproduced cotton for years leading up to the war. Combined with the Union blockade of the South, Columbian warehouses, and even basements and outbuildings of unrelated properties, were packed full of cotton.

A cotton fire in January 1864 had burned down several warehouses, destroying some $3.4 million worth of property and cotton (equivalent to $66,234,894 in 2023). Another fire followed in June 1864, burning even more cotton than the January fire had.

The city of Columbia was of considerable importance to the Confederacy.

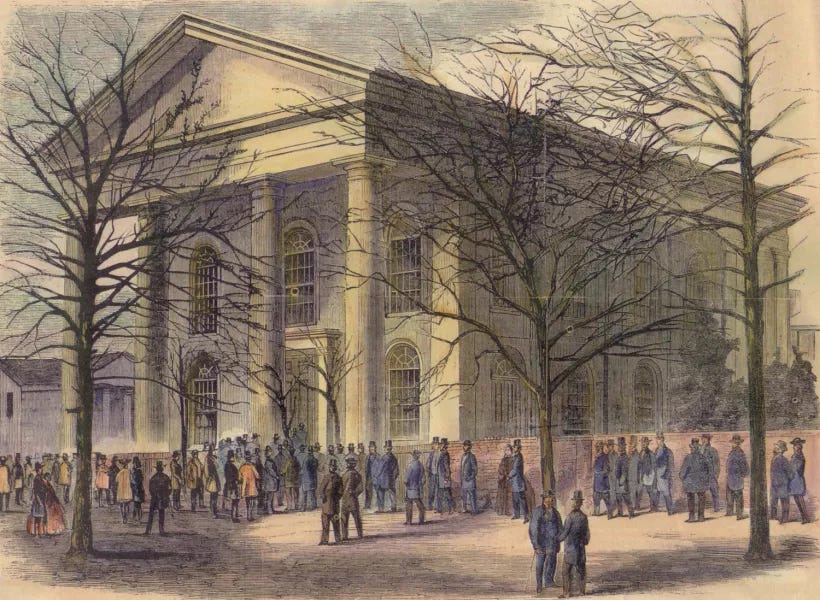

Columbia was the site of the first Southern secession convention, which assembled in the First Baptist Church on December 17, 1860.

Secession may well have been declared in Columbia, however, there was a smallpox outbreak which prompted the convention to move to Charleston, where South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union on December 20, 1860.

A considerable military infrastructure sprung up in Columbia. The state arsenal was located in Columbia, along with the state military academy.

The grounds of the University of South Carolina were converted into a military hospital, since “its role as an educational institution had been made moot after its entire student body volunteered for the Confederate Army.”

In 1863, the city became one of the only domestic sources of medical supplies for the Confederacy, under Dr. Joseph LeConte.

The city's most important industrial contribution was the Palmetto Iron Works, which “in concert with a nearby gunpowder factory, manufactured shells, bullets, and cannons.”

The Confederate Army sock factory was located in Columbia, which worked together with “500 local women who finished the rough socks.”

The Confederate treasury's printing presses were relocated to Columbia in 1862, which was an ever more important enterprise as “inflation forced the printing of $1.5 billion in currency, three times as much as the Union printed.”

The city's strategic importance was made even more clear by being a junction of numerous railroads.

By 1865, it was also the “Confederacy's last breadbasket.”

All of these factors combined to make it the obvious next target for Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman after his successful “March to the Sea.”

Following the fall of Savannah, Georgia, General Sherman “turned his combined armies northward to unite with Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia and to cut General Robert E. Lee's supply lines to the Deep South.”

Sherman planned to march through South Carolina to Columbia, then capture and destroy the Confederate arsenal at Fayetteville, North Carolina, before uniting with the XXIII Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Schofield, at Goldsboro, North Carolina.

To confuse the Confederates, Sherman “sent his left wing westward towards Augusta and his right wing eastward towards Charleston.”

Confused by Sherman’s tactics, Confederate general P. G. T. Beauregard scattered his meager forces in an arc stretching from Charleston through Columbia to Augusta, Georgia, resulting in an inadequate defense for all cities.

In early February, after concentrating his divided columns along a railroad from Windsor to Midway, Sherman marched virtually unopposed on Columbia.

On February 15, 1865, a mere 15 days after entering the Carolinas, Sherman's army had advanced to within four miles of Columbia. Skirmishes broke out repeatedly.

Confederate forces shelled Union troops in their sleep on the night of February 15th, after Union forces gave away their positions by lighting campfires. Sherman was angered by the killing of his sleeping troops, and contemplated retaliation, but decided against it.

The last Confederate troops pulled back across the Saluda and Congaree rivers on February 16, burning the bridges across the rivers, disobeying Confederate general P. G. T. Beauregard's orders.

Confederate sharpshooters harassed Union troops from across the Congaree. Union troops quickly shelled the sharpshooters into silence.

At this point, it “still appeared that the city would not be taken without a fight, and Sherman made plans for its capture.”

Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 26, which was “nearly identical in its terms” to the order issued for the capture of Savannah a couple of months prior:

“General Howard will cross the Saluda and Broad rivers as near their mouths as possible, occupy Columbia, destroy the public buildings, railroad property, manufacturing and machine shops, but will spare libraries and asylums and private dwellings.”

On the morning of February 16, 1865, General William T. Sherman’s Union army, numbering 58,000, stood poised to capture the South Carolina capital.

The unfinished State House was “an easy target for Union cannoneers who bombarded it from the west bank of the Congaree River.” Today, six bronze stars mark the places where shells from their 20-pound Parrott guns damaged the granite walls.

Columbia was in chaos when Mayor Thomas J. Goodwyn surrendered the city at midmorning on Thursday, February 17.

Governor Goodwyn asked on behalf of the citizens of Columbia for “the treatment accorded by the usages of civilized warfare,” requesting “a sufficient guard in advance of the Army to maintain order in the City and to protect the persons and property of the Citizens.”

Confederate General Wade Hampton ordered for stacks of ragged cotton bales to be rolled out of the Columbia warehouses with the intention of burning them — to keep them out of Union hands. The cotton bales lined the streets and strong winds blew the “loose cotton blew over the ground and snagged on buildings and trees, giving the city the appearance of a snowstorm.”

Columbia had “a considerable store of alcohol — much of the alcohol of Charleston had been shipped to Columbia for safekeeping and local merchants had large quantities on hand.” The medical factory also had considerable stores of whiskey.

As the Union troops marched into the city, the citizens of Columbia “began offering alcoholic beverages they had stolen to the Union troops in an ill-thought out attempt to placate their conquerors.”

The Union soldiers, who had “been awake for days and hadn’t eaten in 24 hours” became almost immediately intoxicated by the alcoholic handouts of the onlookers — and steadily dropped out of line.

To quell growing concerns, Union general Oliver O. Howard ordered extensive stocks of alcohol destroyed.

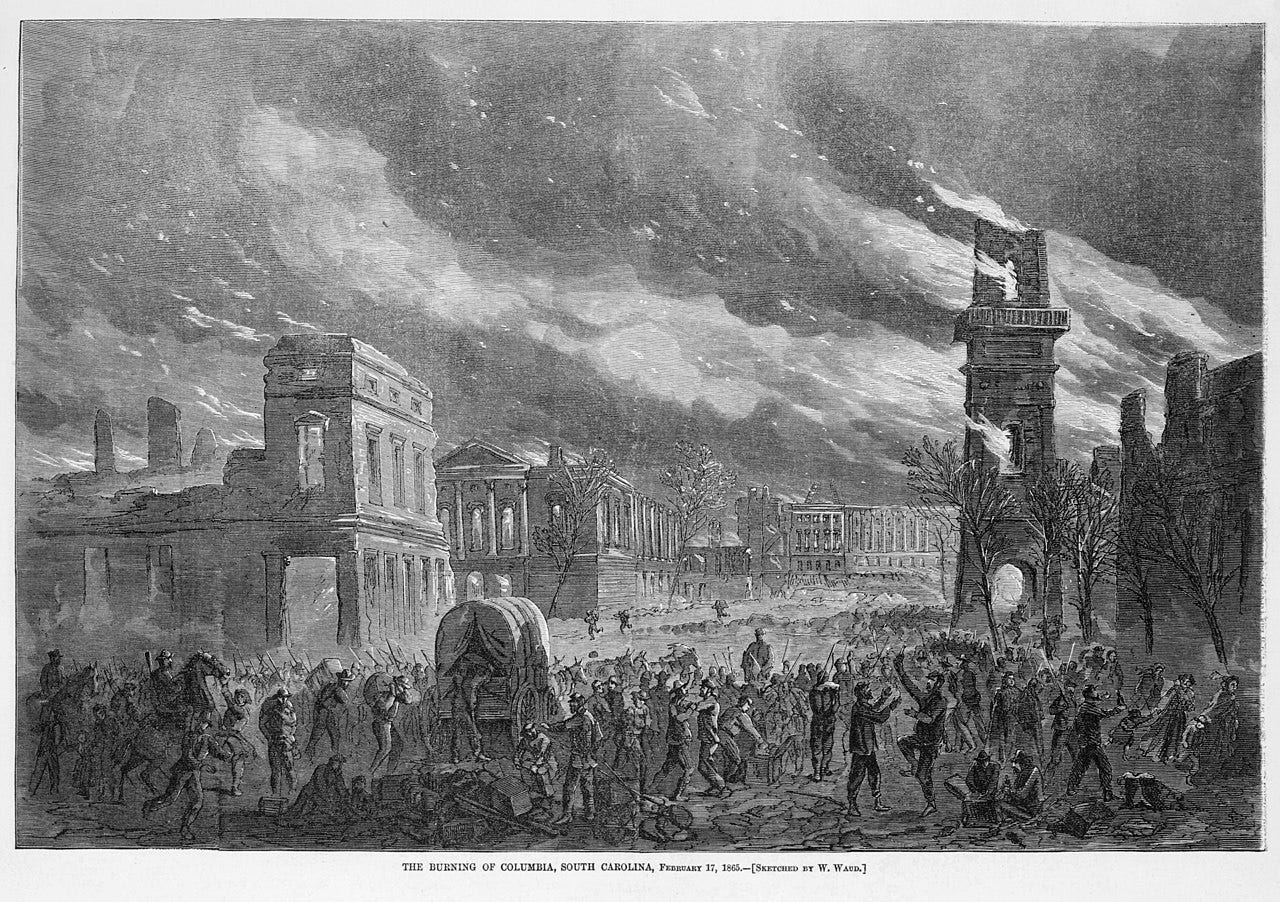

Fires also complicated the evacuation and capture of Columbia. The Congaree River bridge was still smoldering before dawn on February 17 when cotton fires illuminated the city.

Hours later the “South Carolina Railroad depot exploded and burned,” and as their last act, retreating Confederate troops set fire to the Charlotte Railroad depot.

Both stations were still burning about 11:00 am when occupying Union troops reported cotton fires on Richardson (now Main) Street near the town hall. About 1:00 P.M. a blaze flared up at the jail, and during the afternoon at least 6 fires, mostly in cotton stacked in the streets, broke out at downtown locations. Around 8:00 pm, another fire began in the center of town.

At approximately 5:00 pm, as drunkenness increased and security deteriorated, General Howard ordered in fresh troops to arrest disorderly soldiers. The troops arrived about 8:00 pm and “found Richardson Street in flames.”

This last of a series of unexplained fires was the conflagration that burned Columbia. The fire worked its way mercilessly through “wooden buildings with common walls and a strong wind that wafted burning shingles into the air, the fire spread rapidly.”

General Howard, most of the other Union generals, and the local fire companies soon began fighting the fire, but their efforts failed and the flames quickly raged out of control.

General Sherman arrived on the scene about 11:00 P.M.

As the fire spread, a riot unfolded in the streets of Columbia, during which some Union soldiers engaged in “frightful misconduct.” Gangs of troops “taunted citizens, stole or destroyed property, and plundered burning houses.” Other soldiers accosted citizens in the streets and sometimes took their possessions by brute force. Still others engaged in arson, the most notorious of their crimes.

Dr. Robert W. Gibbes, an antiquarian and naturalist, left a detailed account of arson when drunken soldiers burned his home.

Note that accounts of Union soldiers fighting the fires and protecting people and property also exist.

About 3:00 am the wind and the fire subsided. Simultaneously, a fresh brigade of troops entered Columbia and suppressed the riot. In the process, 2 soldiers were killed and 30 wounded; 370 soldiers and civilians were arrested. That “no citizens died during the fire was small consolation.”

When Columbians looked at their city the next morning, they saw massive devastation. About “one-third of the town had burned, totaling 458 buildings, of which 265 were residences.”

Smoke still lingered over the South Carolina capital when “the war of words began” over “Who burned Columbia?”

General Wade Hampton “proclaimed Sherman a barbarian, and South Carolinians began gathering evidence against the Northern commander and his troops.”

Testimony gathered over several years pronounced Sherman guilty, though eyewitness accounts of specific acts of violence and arson were few. In 1873 a claims commission investigating the events in Columbia assessed no blame.

Though traumatic for all inhabitants, the tragic events of the burning of Columbia “were an accident of war, the fault of no single individual.”

The event remains a controversial issue in South Carolina history. Former Confederates and their sympathizers held the event as a “prime example of Northern depravations and cruelty inflicted on Southerners.”

Historian Marion Lucas notes that Sherman's use of “psychological warfare” had long lasting effects: "the trauma of the invasion and burning of Columbia lived on in the minds of South Carolinians in the form of an undying hatred for Sherman and a worship of the 'lost cause.'"

According to contemporary accounts, "The legacy of this physical loss became a pillar of the city’s common folklore and memories of the war, and it remains hotly debated today."

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“O, that long twelve hours! Never surely again will I live through such a night of horrors. The memory of it will haunt me as long as I shall live – it seemed as if the day would never come. The sun rose at last, dim and red through the thick murky atmosphere. It set last night on a beautiful town full of women and children – it shone dully down this morning on smoking ruins and abject misery. [Aunt Josie] thought with us that it was more like the mediaeval pictures of hell than anything she had ever imagined. We do not know the extent of the destruction, but we are told that the greater portion of the town is in ashes. – Perhaps the loveliest town in all our Southern country. This is civilized warfare! This is the way in which the “cultured” Yankee nation wars upon women and children! Failing with our men in the field, this is the way they must conquer!”

— From the diary of 17-yr-old Columbia resident Emma LeConte, February 17, 1865

Sources used in today’s newsletter:

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!

Great piece! Thanks for covering this topic!

One needs to include a bibliography in their writings, so the reader may see your sources. I would also advise you to look at Rev. William Porter’s journal and Dr Rob Andrew’s book on General Wade Hampton about the burning of Columbia, South Carolina. With the theory of historiography, one must not take a writer’s word because of his or her agenda with their writings.