#90: Confederate soldiers States Rights Gist and Manse Jolley, and a lecture on Modernism in Historic Charleston

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #90 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

tricksathicks

karenlucking

ctanner100

bamaanne

stclip

ginnyo1980

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

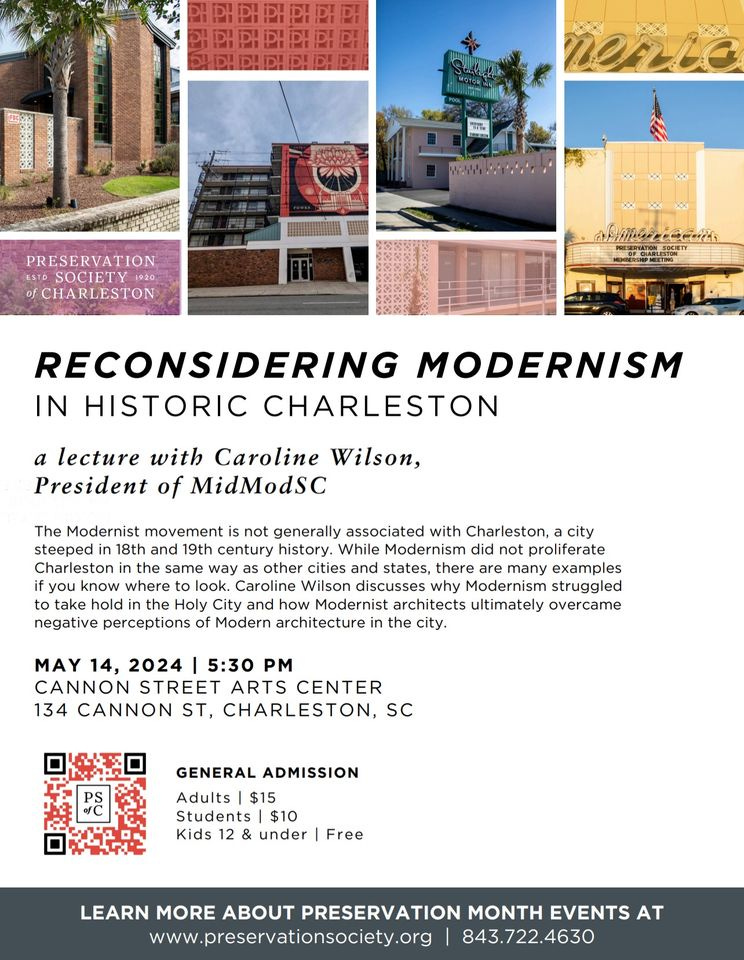

Tuesday, May 14th at 5:30 pm | “Reconsidering Modernism in Historic Charleston” | Cannon Street Arts Center | Charleston, SC | $15 Adults, $10 Students, FREE kids 12 and under

“Charleston is a city steeped in 18th and 19th-century history, but there are many examples of Modernism if you know where to look. Join us for a lecture with architectural historian Caroline Wilson, founding member and president of MidModSC, a non-profit documenting and preserving South Carolina’s Modernist architecture.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Did you know that there was a Confederate brigadier general named States Rights Gist?

(Note from Kate: I’d like to thank subscriber for encouraging me to write about our first interesting historical figure of the day below!)

States Rights Gist (September 3, 1831 – November 30, 1864) was born at his family’s home (called “Wyoming”) in the Union District of South Carolina to Nathaniel Gist and Elizabeth Lewis McDaniel. He was the 9th of 10 children.

Gist was born during the Nullification Crisis and his name reflected the “Southern states' rights doctrine of nullification politics of his father,” who was a disciple of John C. Calhoun.

He was known to his family as “States.”

He graduated from South Carolina College, now the University of South Carolina, and thereafter graduated from Harvard Law School.

With his law degree in hand, Gist returned to Unionville, SC, passed the bar exam, and set up his law practice.

In the years that followed, Gist’s star would quickly rise through a series of family, military, and political alliances.

In 1853, Gist served in the SC state militia as captain of the Johnson Rifles.

In 1854, Governor James H. Adams (in office from 1854-1856) appointed Gist his aide-de-camp with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

In 1856, at age 24, Gist was elected brigadier general, commanding the Ninth Brigade.

In 1858, his cousin, Governor William Henry Gist, appointed him his “Especial Aid-de-Camp.”

In January 1861, Governor Francis W. Pickens (in office 1860-1862) appointed Gist the state’s Adjutant and Inspector General.

After the bombardment of Fort Sumter in April 1861, and the commencement of the Civil War, Gist went to Virginia and served as a volunteer aide on the staff of Brigadier General Bernard E. Bee.

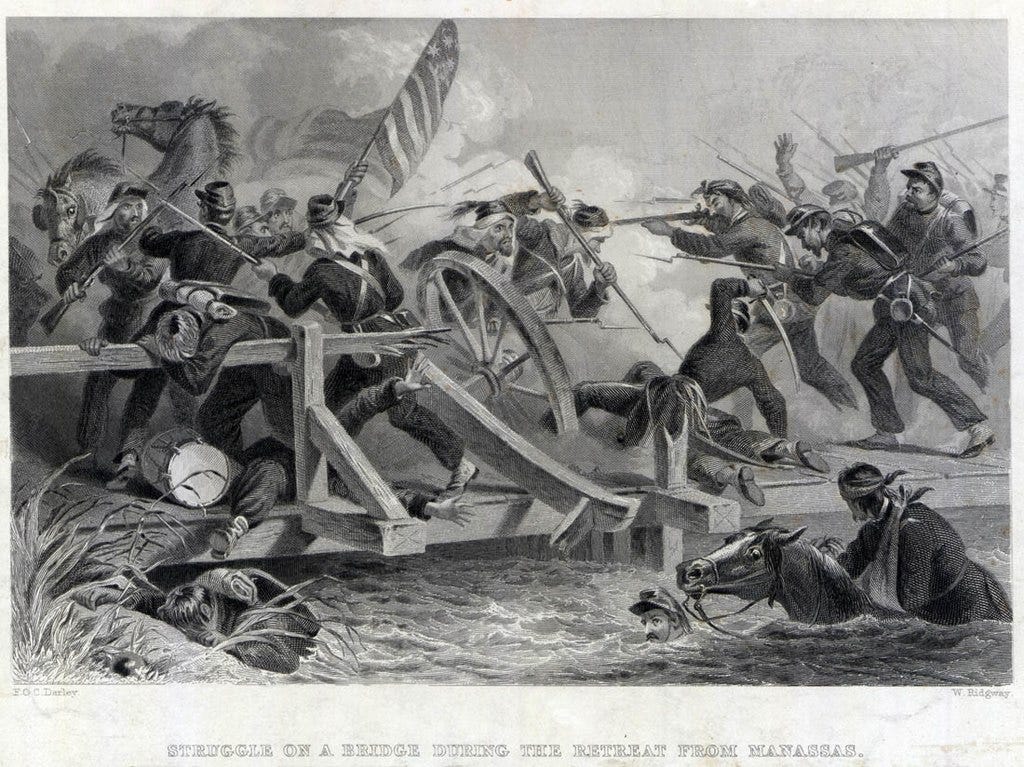

At the Battle of First Manassas — the first major battle of the American Civil War — General Bee was mortally wounded and Gist was given command of the remnants of the South Carolinian’s brigade.

Gist was wounded in battle as well, but recovered, and returned to South Carolina to resume his duties as Adjutant and Inspector General.

On March 20, 1862, Gist resigned his role as Adjutant and Inspector General and accepted a commission as brigadier general in the Confederate army. He was assigned to the Charleston area, and with the exception of a brief assignment in North Carolina, General Gist served in the defense of the city until May 1863.

On May 3, 1863, Gist was given command of an infantry brigade and “ordered to join a column assembling at Jackson, Mississippi, in response to federal operations against Vicksburg.”

Just before leaving, he married Jane M. Adams, daughter of former Governor James H. Adams, who Gist had served earlier in his career as aide-de-camp.

After they were married, Gift spent just 2 days with his wife, and then headed west.

Gist saw limited action in the Vicksburg campaign. Following the city’s surrender, he was ordered to reinforce the Army of Tennessee in northern Georgia.

At the battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga, and throughout the Atlanta Campaign, Gist proved “a reliable and respected commander.”

Following the evacuation of Atlanta, the Army of Tennessee advanced north and in November entered Tennessee. While leading his brigade in the November 30, 1864, Battle of Franklin, Gist was wounded twice, in the thigh and then in the chest. The second wound proved fatal. Gist was one of 6 Confederate generals killed or mortally wounded in the battle.

States Rights Gist was buried in a local family cemetery in Tennessee, but in 1866 his remains were returned to South Carolina and interred in the Trinity Episcopal Church cemetery in Columbia.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you also know that there was a Confederate soldier Manse Jolley, who in the aftermath of the Civil War became known as the “Yankee killer”?

(Note from Kate: I’d like to thank subscriber for encouraging me to write about our 2nd interesting historical figure of the day below!)

Manson Sherrill (Manse) Jolly was from the Anderson district of South Carolina and was described as "six feet four inches high, ruddy complexion, blue eyes, red hair, and by profession a farmer.”

Jolly enlisted in the Confederate Army in February 1861. He served through most of the war “from Manassas to Appomattox, as a cavalry scout.”

One man who served with Jolly recalled an incident where the two men “crept up to a Yankee outpost of three Union soldiers, all of whom were quietly dispatched by Jolly’s knife.”

Another companion recalled “Jolly leaving camp one night and returning with the horse and saddle of a Union officer, which he politely presented to his captain.”

Jolly was apparently in Wade Hampton’s cavalry forces when Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox and headed homeward — but Jolly vowed never to surrender.

All 5 of his brothers had died in service to the Confederacy. Four were killed in battles, the fifth died in an army hospital.

Coming home to the scene of early Reconstruction in his hometown was clearly a shock to Jolly. He witnessed a “miserable Anderson County occupied by Massachusetts troops, including Negroes…Carpetbaggers, freed-men, and Union troops.”

Furthermore, “after his mother and sisters were abused by Federal troops, he became head of a small band of guerillas dedicated to giving the occupational troops a hard time.”

Whether by choice or by circumstance, the embittered, “unsurrendered” Sgt. Jolly became a “scourge of the occupiers” when he began his quest for revenge.

Jolly became known as the “champion Yankee killer.” He swore to kill a quota of Yankees for each of the 5 brothers. There is no agreement on exactly how many he killed — “estimates vary from about 15 on up to 100.” It is also suspected that Jolly killed freed slaves well.

A remarkable discovery occurred when David J. Watson, a retired engineer who had “been in charge of the physical plant at Clemson University” and was a leader in local historical societies, purchased the Manse Jolly log cabin home near Anderson, SC and began to remodel the structure. Here is a sketch of the Manse Jolly cabin:

As a part of restoring the cabin, Watson cleaned out the old well on the Jolly farm. The well “contained numerous skeletons and about a peck of corroded military uniform buttons — all marked ‘U.S.’” The well was deemed one of “Manse Jolly’s disposal spots for the Yankee soldiers he killed.”

From the Dallas Morning News article:

“He (Jolly) obviously considered himself a guerrilla, carrying on the war against an occupation enemy. He circulated freely in his old haunts, even in Anderson. The Union didn’t know him by sight, and when the price on his head rose even as high a $10,000 there were no takers. Obviously, anyone attempting to collect it, in person or by proxy, would not have lived long enough to spend it. Some of the people of the area were nervous because of his activities, and the Yankee heat it focused, but to most of the people, he was a Robin Hood netting out justified justice.”

The Anderson Intelligencer newspaper wrote:

“Jolly was the most wanted man in Western South Carolina. The United States Army not only put a price on his head, but often sent instructions to bring him in dead or alive.”

With a price on his head, and one too many narrow escapes from his enemies, Jolly eventually decided to leave South Carolina and start a new life in Texas.

The story goes that he left Anderson in a “blaze of glory” on Sunday, January 29, 1866.

Jolly rode quietly into Anderson on his favorite horse, Dixie. A few blocks down the street from the camp of the Union troops, he reined up. Taking a deep breath, he pulled his hat down over his red hair, and put a pistol in each hand. With the “traditional rebel-yell piercing the calm day, he galloped pell-mell through the camp with both pistols blazing at anything that moved. The troops, understandably, were stunned into virtual statues until the yelling apparition had disappeared into protecting woods, leaving shocked and wounded soldiers in his wake.”

Jolly traveled to Texas with his companions (some of whom helped him harass the Union soldiers) Walter Largent, F.D. Townsend, Thomas Herbert Williams, and a cousin, John M. Jolty.

Once in Texas, Jolly and his companions lived in a small farm building Manse labeled “Bachelor’s Hall” in his letters home. In one letter he calls it “Delectable Hall.” They worked long hours at raising cotton and wheat, and Manse worked at a gin.

Letters from Jolly survive today and here are a few excerpts:

On April 16, 1867, he wrote his sister: “I am more than pleased with Texas, but damn the people that live in it. Society is bad, no use for preachers out here…”

On June 29 he had another appraisal of frontier Texas: “The longer I stay the better satisfied I am but I say darn the most of the people. It has become a general custom amongst the lower class to use snuff. How distasteful it is in my sight to see them push forward a box of snuff and ask all around to dip with them corn is selling for 50 cts per bushel, flour 10 dollars per barrel, bacon 12 ½ cts per pound, beef from one to three cents …”In the same letter he also noted:

“I am strongly in the notion of getting married as a bachelor’s life is most miserable of all living creatures.”

Jolly wasn’t a bachelor for long. In 1868, he married 19-year-old Elizabeth Mildred Smith, a daughter of Capt. John Grey (Jack) Smith, another South Carolinian.

Yet only 1 year later, tragedy truck when Jolly drowned on July 8, 1869. He was working on building a house, and was crossing a creek with his horse when the water rose so quickly that he was unable to escape. He was 29 years old.

Manse Jolly was buried in Texas. He was a Mason , and you will notice his grave below has the masonic symbol on it.

In his obituary below from the Anderson Intelligencer, it notes:

“The thrilling exploits and adventures of Manson Jolly in this section of the country, immediately after the war closed, are fresh in the recollection of all. His name was a terror, for a long time, to the garrison of United States soldiers — especially the volunteer white and colored regiments — stationed at this place. When the regular troops arrived, he removed to Texas where he has since been leading a quiet and peaceful life.”

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“Whereas, the Grand Architect of the Universe, in the wise dispensation of his Providence, has seen proper to call from earthly labor our beloved brother, Manson S. Jolly; and whereas, in his death the Craft has lost a faithful laborer, and the order a model workman. Therefore, be it resolved that we deeply deplore the untimely separation from our Brotherhood of our beloved brother, Manson S. Jolly.”

— Taken from an obituary for Manse Jolly from San Andres Masonic Lodge, Texas

States Rights Gist article sources:

Hatcher, Richard W. “Gist, States Rights.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/gist-states-rights/. Accessed 10 May 2024.

Manse Jolley article sources:

“Manson Sherrill ‘Manse’ Jolly.” Cathedral of Liberty – Preserving Revolutionary & Civil War History, 1 Apr. 2021, https://cthl.org/american-civil-war/manson-sherrill-manse-jolly/. Accessed 10 May 2024.

“Manson Sherrill ‘Manse’ Jolly (1840-1869).” Find a Grave - Millions of Cemetery Records, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7798336/manson-sherrill-jolly#view-photo=205602810. Accessed 10 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!