#145: History of SC Founding Mothers + Spy Camp at Walnut Grove Plantation

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, upcoming SC historical events, and other South Carolina recommendations.

Dear readers,

Happy belated Mother’s Day! Cheers to all the wonderful mothers, stepmothers, and grandmothers who we love and cherish so much!

In honor of Mother’s Day, I decided to feature some of South Carolina’s “founding mothers” in our history essay below. I hope you enjoy.

Now, let’s learn some history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Support the SC History Newsletter by considering heritages teas (inspired by South Carolina and American history!) from our fantastic sponsor Oliver Pluff & Co. — click on their beautiful ad below! :)

➳ Housekeeping for new subscribers!

New friends! There are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and more! See our archive here!

Send me your comments or topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Have additional ideas or feedback? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Keep the conversation going and join over 100 other subscribers by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here!

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

Love the SC History Newsletter? Please click the button below to share with a friend!

➳ Featured SC History Event of the Week:

🗓️June 16th-20th, 9am-12pm

📝 American History “Spy Camp”

📍Walnut Grove Plantation | Spartanburg, SC

🎟️$150, Ages 6-12

💻 Website

From the camp website:

“Embark on a journey into the world of Revolutionary War espionage at Spy Camp.

Campers will uncover the secrets of 18th-century spycraft, from creating disguises and cracking codes to navigating stealth missions and decoding enemy plans. Through hands-on activities and covert operations, kids will step into the shoes of Patriot spies and experience the excitement of history in action.”

➳ 🗓️ Paid subscribers get access to my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

➳ History of South Carolina Founding Mothers

In honor of Mother’s Day, I thought it would be fun to feature some of South Carolina’s “Founding Mothers” below — enjoy!

🌿 Eliza Lucas Pinckney (1722–1793)

The Teen Who Transformed the South Carolina Economy

Eliza Lucas Pinckney is one of South Carolina’s most famous founding mothers.

She was born Eliza Lucas in Colonial British Antigua as the eldest daughter of George Lucas, Lieutenant Governor of the Island. She was sent away for schooling in London at an early age, where she proved to be highly intelligent, and was particularly drawn to the study of botany — a key element to her famous story.

Circa 1738, the Lucas family owned 3 plantations from Antigua to Charleston — Garden Hill Plantation, Wappoo Plantation, and 3,000 acres on the Waccamaw River near Georgetown.

In this same time period, Eliza’s mother fell ill and her father had to return to Antigua for political reasons. With her brothers at school in England, Eliza (a teenager!) had to step up and manage her family’s Charleston-based plantations, including the enslaved workers on the properties.

As she managed her family’s plantations, Eliza brought her botanical learning to good use. England had encouraged the colonists to experiment with various cash crops. While Carolina Gold Rice at the time was the dominant cash crop of the South Carolina economy, at age 19, Eliza began other botanical experiments.

At one point, Elizabe planted a large fig orchard with the idea of drying and exporting the figs. She also though to grow large oak trees to one day sell for shipbuilding.

While it was customary for the planter class to frequently socialize in Charleston, Eliza was often too busy overseeing her plantations, their many slaves, and her botanical experiments.

The Pinckney family, who lived nearby, acted as guardians and friends to Eliza while her father remained in Antigua. Her relationship with the Pinckneys was quite close.

Charles Pinckney was very skeptical of Eliza’s interest in planting. He wrote, “Tell the little visionary come to town and partake of some of the amusements suitable to her time of life.” To which Eliza responded “Pray tell him…what he may now think whims and projects may turn out well by and by. Out of many surely one may hit.”

And one project hit… and it hit BIG… indigo!

Indigo was a crop truly prized by the British empire. Though many believed the Lowcountry Charleston environment wouldn’t be suitable for indigo production. Though years of persistence, Eliza Lucas Pinckney, cracked the code for the indigo crop to thrive.

In 1744, she was able to grow enough indigo to begin the process of dye production.

According to the National Parks Service:

“She [Eliza] sent a substantial export of indigo to England as proof of her efforts. In addition to economic motives, indigo production also succeeded in the Lowcountry because it fit within the existing agricultural economy. The crop could be grown on land not suited for rice and tended by enslaved people, so planters and farmers already committed to plantation agriculture did not have to reconfigure their land and labor. In 1747, 138,300 pounds of dye, worth £16,803 sterling, were exported to England. The amount and value of indigo exports increased in subsequent years, peaking in 1775 with a total of 1,122,200 pounds, valued at £242,295 sterling. England received almost all Carolina indigo exports, although by the 1760s a small percentage was being shipped to northern colonies.”

By the beginning of the American Revolution, indigo made up one third of the exports from South Carolina!

In her personal life, Eliza’s neighbor Charles Pinckney lost his wife and he and Eliza married. They had 4 children together, including Charles Cotesworth Pinckney would go on to serve “as a Framer during the Constitutional Convention.”

Eliza would outlive her husband, who sadly died of malaria in 1758. Her children went on to have “lasting impacts on the foundation of the United States” and Eliza continued to experiment with other crops and products, including silk.

She developed breast cancer in her 70s, and her children took her to Philadelphia to receive the best medical treatment. She died in Philadelphia and is buried at St. Peter’s Churchyard. George Washington, by his own request, was a pallbearer at her funeral. Her impact as a founding mother of not only South Carolina, but the young American Nation, was felt deeply.

Eliza Lucas Pinckney’s left a lasting legacy in the Lowcountry. In 1989, Eliza was the first woman inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame, for her contributions to agriculture and economic growth. In 2008, she was inducted in the South Carolina Hall of Fame.

See our SC History Newsletter podcast/YouTube interview below with Charleston Museum textile curator, Virginia Theerman, as she walks us through the history of Eliza Lucas Pinckney’s “Robe a la Francaise.”

Eliza Lucas Pinckney’s left a lasting legacy in the Lowcountry. In 1989, Eliza was the first woman inducted into the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame, for her contributions to agriculture and economic growth. In 2008, she was inducted in the South Carolina Hall of Fame.

🔥 Rebecca Brewton Motte (1737–1815)

The Woman Who Torched Her Own Mansion for Freedom

Rebecca Brewton Motte was one of South Carolina’s most courageous Revolutionary heroines.

Born into wealth along the Santee River, she was the sister of Miles Brewton —South Carolina’s largest slave trader and builder of Charleston’s famed Miles Brewton House.

After Miles and his family were tragically lost at sea en route to Philadelphia, Rebecca and her sister inherited his vast estate, including his grand townhouse several plantations, and 244 slaves.

At age 21, Rebecca married Jacob Motte, a Charleston planter and politician. They had 7 children together but only 3 survived to adulthood. The couple supported the Patriot cause during the Revolutionary War — supplying the Continental Army with food and resources.

Jacob Motte sadly died in 1780, but Rebecca continued aiding the Revolution. She sent enslaved workers to help build Charleston’s defenses and later took in Patriot officers at her plantation, Buckhead.

In the spring of 1781, British Lt. Donald McPherson arrived at the plantation and “banished Rebecca and her family to one of the plantation’s outbuildings.” The British converted Rebecca’s three-story house into a veritable fortress, surrounding it with a “wooden palisade reinforced with a rampart and supported by blockhouses manned by a garrison of 165 men.” It would become known as Fort Motte.

On May 8th 1781, patriots Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee and Brigadier General Francis Marion arrived to lay siege to Fort Motte and defeat the British. Rebecca offered her temporary home as headquarters for the cause. As the patriots made their battle plans, Rebecca bravely offered Lee her own bow, which he used on May 12th to begin the attack and set fire to her home

The Capture of Fort Motte, see Rebecca in the center of the painting (Image Source) The roof caught fire, the Patriots attacked, and the British surrendered. The fire was extinguished before the house was lost, and Rebecca and her children returned home.

Though her estate suffered financially after the war, Rebecca rebuilt the family fortune. She lived to see her grandchildren play in the very home that had once been the British-occupied “Fort Motte.”

Today, Rebecca Brewton Motte is remembered not only as a wealthy Charlestonian but as a woman of exceptional courage, patriotism, and sacrifice.

🏛️ Ann Pamela Cunningham (1816–1875)

The Savior of Mount Vernon

Ann Pamela Cunningham, born on Rosemont Plantation in Laurens County, South Carolina, grew up riding horses and receiving a classical home education. A riding accident in her teens left her disabled for life, but it never dimmed her vision or resolve.

Her defining moment came in 1853, when her mother, traveling by steamboat along the Potomac River, caught sight of a decaying Mount Vernon—the former home of George Washington. Distressed, she wrote to her daughter Ann: “Why was it that the women of his country did not try to keep it in repair, if the men could not do it?” That challenge changed Ann’s life—and the future of American preservation.

Anne Pamela Cunningham (Image Source) At age 37, Ann published an open letter in the Charleston Mercury, calling on “the Ladies of the South” to raise funds to save Mount Vernon.

Congress and Virginia had refused to purchase the property, and speculators threatened to buy it.

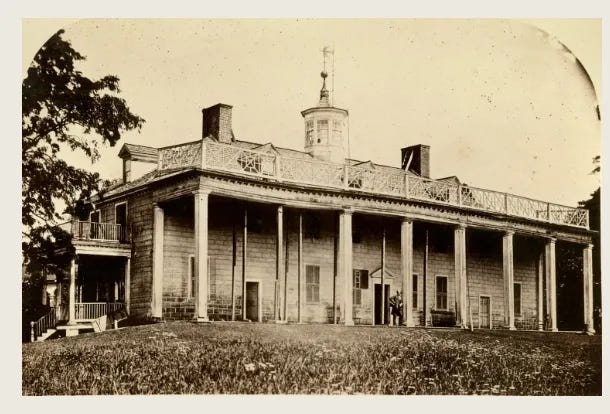

Mount Vernon in ruins (Image Source) In response, Ann formed The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association — the first historic preservation organization in the U.S. — and served as its first regent.

She recruited influential women across all 30 states to serve as vice regents, each tasked with fundraising in their state. Thanks to her leadership, the association raised $200,000 (equivalent to over $5 million today) and purchased Mount Vernon and its 200 acres.

Regent Ann Pamela Cunningham (facing bust of George Washington in the middle) and the first members of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association pose for a photograph near the east front of the Mount Vernon Mansion, 1870. (Image Source) The Mount Vernon Ladies Association still manages the estate today. The site relies on private donations and does not receive any governmental funding.

Though she never married or had children, Ann Pamela Cunningham’s legacy lives on through every visitor to Mount Vernon. She proved that patriotic women could move a nation — and mother a movement — when others would not.

Many thanks to all SC History Newsletter subscribers who helped me raise over $500 towards the continued preservation of Mount Vernon for my birthday this past January!

Furthermore, I hope and plan to be at Mount Vernon for July 4th, 2026 for the America250 celebration! Will you?

🕍 Penina Moïse (1797–1880)

The Voice of Jewish Charleston

Penina Moise was born in 1797 to a large and wealthy Jewish family in Charleston, SC. She would become one of American’s best-known Jewish poets and served the Jewish community of Charleston as an advocate and educator.

She was born to Abraham and Sarah Moise. She was the 6th of 9 children. She served as the family nurse, caring for her mother and her brother Isaac, who suffered from asthma.

Penina herself had terrible eyesight that unfortunately deteriorated into blindness during the Civil War.

Penina grew up “in the presence of a diverse, vital, and well-integrated Jewish community,” and she devoted herself to Jewish issues.

South Carolina is home to the oldest Jewish community in the South, with Jewish colonists arriving in Charleston in the late 17th century. Charleston continued to be a leading center of American Jewish life throughout the 18th century.

In 1820, Charleston was home to the largest Jewish community in the country.

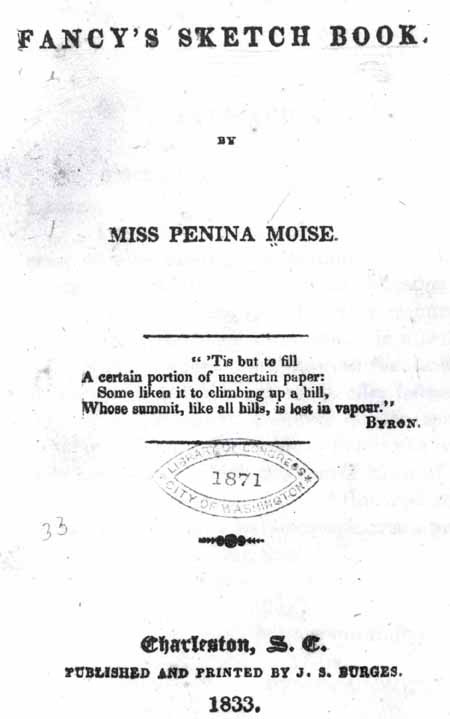

She had a gift for poetry and her siblings encouraged her to write a collection of poems, which she did in 1833. The collection was entitled Fancy’s Sketch Book, and was the first ever written by a Jewish American woman.

Penina also wrote columns for newspapers throughout the United States. According to the Jewish American Archive, “Her poetry covered a variety of topics, including current events, politics, local life, Judaism, Jewish rights, and Jewish ritual reform.”

Along with her literary works, Penina “devoted her life to teaching.”

In 1845, she became the second superintendent of Congregation Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim’s Sunday school.

The Civil War forced Penina out of Charleston (she temporarily relocated to Charleston), and she returned to the city after the war with drastically reduced means. She supported herself by running an academy with her widowed sister and her niece. Though “self-conscious about her poverty, she accepted it with humor and grace.”

Penina Moise was the first Jewish American woman to also contribute to the Jewish worship service, writing 190 hymns for Beth Elohim.

Here is a sample of her poem Behold the Synagogue:

He sings again beneath the star

Of Freedom’s Holy Land;

And Hallelujahs heard afar

Resound from Israel’s band.

Lips are the only censers now.

To waft the heart’s oblation

On these, Eternal Ruler! throw

Thy spirit’s radiation.

🕯️Hidden Heroines: Enslaved Women Who Shaped South Carolina

In Bondage, In Bravery: South Carolina’s Enslaved Heroines

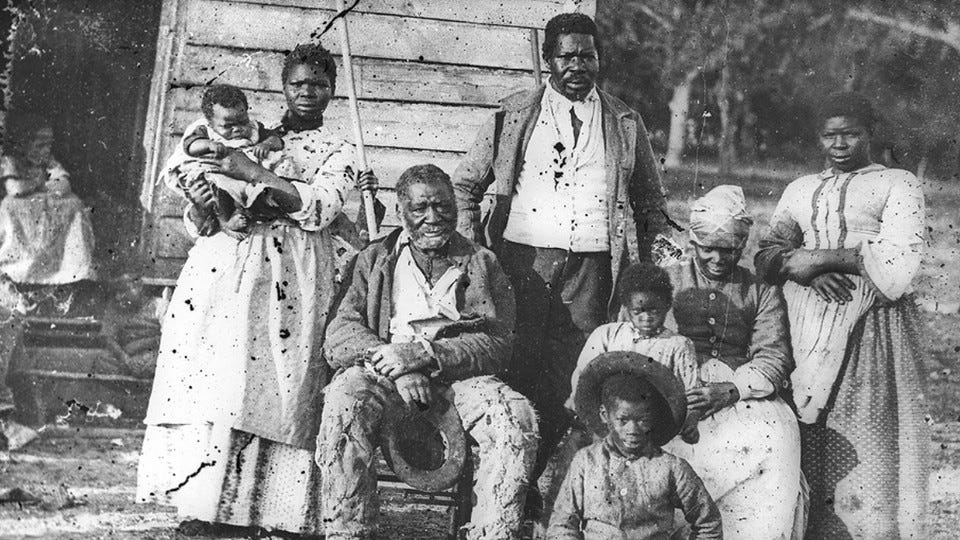

It is also important to acknowledge the thousands of enslaved women who were mothers on antebellum South Carolina plantations.

Enslaved women found parenthood “a source of joy and comfort, as many WPA interviews with formerly enslaved women in the 1930s convey.”

Enduring physical labor, family separation through sale, illness, and many more evils, these women persevered and gave birth against the odds.

Enslaved women passed their skills and heritage on to their daughters, especially the arts of cooking and herbal medicines.

In one WPA interview from the 1930s, a woman named Ryer Emmanuel gave insight from a child’s perspective on what it was like to witness the “multiple roles of mothers and childcare under enslavement.”

"Always when a woman would get in de house [to have a baby], old Massa would let her leave off work wen stay dere to de house a month till she get mended in de body way. Den she would have to carry de child to de big house en get back in de field to work. Oh, dey had a old woman in de yard to de house to stay dere en mind all de plantation chillun till night come, while dey parents was workin. Dey would let de chillun go home wid dey mammy to spend de night en den she would have to march dem right back to de yard de next morning. We didn’ do nothin’, but play ‘bout de yard dere en eat what de woman feed us. Yes’um, dey would carry us dere when de women would be gwine to work. Be dere fore sunrise. Would give us three meals a day cause de old women always five us supper fore us mammy come out de fields dat evenin."

Enslaved women provided the majority of the nursing work on plantations — caring for their fellow enslaved workers in “sick houses” and plantation hospitals.

As historian Sharla Fett notes in her book Working Cures, “Enslaved women grew herbs, made medicines, cared for the sick, prepared the dead for burial, and attended births.”

Enslaved women also cared for the children of their masters, some even working as wet nurses at the beginning stages of the infant’s lives. These women cared for their master’s extended family as well, “attending births and providing child care, sick care, and elder care.” Enslaved women also served as nurses and surgical assistants to plantation owners and visiting doctors as well.

I hope we can collectively salute these brave enslaved mothers who — though many of their names and identities are lost to history — made essential contributions not only to their slave communities, but to the communities of the plantation elite (and beyond) of the Lowcountry in the Antebellum era.

If you voted just “OK” on the newsletter today, I want to hear from you! Reply to this email and send me your feedback. :)

➳ Sources — History of South Carolina Founding Mothers

“Ann Pamela Cunningham.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/ann-pamela-cunningham. Accessed 11 May 2025.

“Eliza Lucas Pinckney.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/chpi/learn/historyculture/eliza-lucas-pinckney.htm. Accessed 11 May 2025.

“Hidden Voices: Enslaved Women, Their Families, and the Archive – Motherhood and Children.” Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/hidden-voices/enslaved-women-their-families/motherhood-and-children. Accessed 11 May 2025.

“Make No Doubt We Shall Carry This Post: The History and Archaeology of Fort Motte.” South Carolina Humanities, https://schumanities.org/make-no-doubt-we-shall-carry-this-post-the-history-and-archaeology-of-fort-motte. Accessed 11 May 2025.

“Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/preservation/mount-vernon-ladies-association. Accessed 11 May 2025.

“Penina Moïse.” Jewish Women’s Archive, https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/moise-penina. Accessed 11 May 2025.

“Rebecca Motte.” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/rebecca-motte. Accessed 11 May 2025.

“South Carolina.” Institute of Southern Jewish Life Encyclopedia, https://www.isjl.org/south-carolina-encyclopedia.html. Accessed 11 May 2025.

“‘We Are His Nurses’: On Plantations, Enslaved Women Cared for Each Other.” University of Virginia School of Nursing, https://nursing.virginia.edu/news/mhm-nursing-enslaved-plantations. Accessed 11 May 2025.