#124: History of Hunting in South Carolina, Holidays with the Heywards, and Taste the State

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, interviews w/ experts, book recommendations, and upcoming SC historical events.

Dear reader,

Welcome to SC History Newsletter #124!

I hope everyone had a wonderful Thanksgiving! Please reply to this email and send me some stories of your family adventures. :)

Today we are going to dive into the history of hunting in South Carolina.

Enjoy!

New friends! If you are new to the newsletter, please note that there are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and so much more! I encourage you to take a look at our archive here.

Send me your topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you. :)

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Events

Please note our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered.

Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

Event Recommendation of the Week:

Thursday, December 5th | “Holidays with the Heywards Tour” | The Heyward-Washington House | Charleston, SC | Website

“Celebrate this holiday season at the Heyward-Washington House! Join Curator of History Chad Stewart for a themed guided tour of the Heyward-Washington House. Learn how early Americans celebrated the winter holidays. Experience the Heyward-Washington House decorated for Christmas and indulge in holiday punch and cookies as you celebrate the season as the Heywards would!

Guests are invited to explore the interior of the Heyward-Washington House before the holiday tour commences at 4:00 pm. Holiday themed refreshments will be served prior to the tour.

This tour is FREE for Members and FREE with admission to the Heyward-Washington House. The last tour of the day of the interior of the Heyward-Washington House is at 4:15pm.”

➳ SC History Book, Article, & Movie Recommendations

“Taste the State: South Carolina's Signature Foods, Recipes, and Their Stories” by Kevin Mitchell and David Shields

(A note from Kate: today I thought I would spice things up by including a cookbook! Exciting to explore South Carolina’s history through food!)

Here is the publisher’s description:

“Bitter Southerner 2022 Summer Reading pick • Garden & Gun Best Southern Cookbooks pick • Forbes Best New Cookbooks For Travelers pick • 2021 Gourmand International Cookbook Award Finalist

From the influence of 1920 fashion on asparagus growers to an heirloom watermelon lost and found, Taste the State abounds with surprising stories from South Carolina's singularly rich food tradition. Here, Kevin Mitchell and David S. Shields present engaging profiles of eighty-two of the state's most distinctive ingredients, such as Carolina Gold rice, Sea Island White Flint corn, and the cone-shaped Charleston Wakefield cabbage, and signature dishes, such as shrimp and grits, chicken bog, okra soup, Frogmore stew, and crab rice. These portraits, illustrated with original photographs and historical drawings, provide origin stories and tales of kitchen creativity and agricultural innovation; historical "receipts" and modern recipes, including Chef Mitchell's distillation of traditions in Hoppin' John fritters, okra and crab stew, and more.

Because Carolina cookery combines ingredients and cooking techniques of three greatly divergent cultural traditions, there is more than a little novelty and variety in the food. In Taste the State Mitchell and Shields celebrate the contributions of Native Americans (hominy grits, squashes, and beans), the Gullah Geechee (field peas, okra, guinea squash, rice, and sorghum), and European settlers (garden vegetables, grains, pigs, and cattle) in the mixture of ingredients and techniques that would become Carolina cooking. They also explore the specialties of every region―the famous rice and seafood dishes of the lowcountry; the Pee Dee's catfish and pinebark stews; the smothered cabbage, pumpkin chips, and mustard-based barbecue of the Dutch Fork and Orangeburg; the red chicken stew of the midlands; and the chestnuts, chinquapins, and corn bread recipes of mountain upstate.

Taste the State presents the cultural histories of native ingredients and showcases the evolution of the dishes and the variety of preparations that have emerged. Here you will find true Carolina cooking in all of its cultural depth, historical vividness, and sumptuous splendor―from the plain home cooking of sweet potato pone to Lady Baltimore cake worthy of a Charleston society banquet.”

Have you read this cookbook? Tell us your review! Leave a comment below!

➳ SC History Topic of the Week:

The History of Hunting in South Carolina

Hunting on the land (that is now South Carolina) has occurred here for thousands of years. Native Americans hunted a wide variety of game in this region as early as 13,000 BCE and continued to hunt on South Carolina lands well after European colonists arrived.

Native tribes hunted “deer, mountain lions, raccoon, rabbit, bear, and other animals for meat and skins, while taking birds for food and feathers.”

Early European colonists also hunted and depended on wild game for survival.

Colonial hunting laws were fairly relaxed which resulted in areas of land being easily overhunted by Native American, European, and enslaved African hunters.

“Ring fire hunting” was a Native American hunting technique in which hunters would set fire around a large stretch of woods — sometimes up to widths of nearly 5 miles. The fire would drive the game toward the center of the ring, where the hunters could easily target their prey. The fires, while destructive, would in some cases help the forest ecosystem, especially the reproductive cycles of certain trees such as the longleaf pine.

Eighteenth century explorer John Lawson witnessed Native Americans using this method in 1709:

“Thus they go and fire the Woods for many Miles, and drive the Deer and other Game into small Necks of Land and Isthmuses where they kill and destroy what they please.”

There was yet another hunting technique in this time period — “night hunting by firelight” — in which one hunter (usually a slave) would hold glowing embers, while the other hunter walked in front “watching for reflections from animals’ eyes.” Animals caught in the light became transfixed, providing the hunter with an easy shot. This method was quickly condemned because, in the darkness, hunters “occasionally mistook livestock for wild game.”

In an effort to protect deer populations, Southern colonies “prohibited hunting during the months when females carried and cared for their young.”

Virginia passed a deer season in 1730, and North Carolina followed suit in 1745. However, colonial governments lacked the resources to enforce these laws. Most hunters ignored the laws and continued, unchecked, to provide for themselves and their families.

Much of the 18th century trade between European colonists and the Native tribes was based on the exchange of animal skins.

By the time of the Revolutionary War, Carolinians began to view “hunting as a sport” versus a necessity. It was during this period that they also began to see the detrimental effects of unrestricted hunting and began to enact laws to protect the wildlife of their region.

In the height of the Antebellum era, rich South Carolina planters would “game for sport, for food, to protect livestock and crops, and to fulfill their cultural traditions.”

In this period, sporting publications began to emerge:

“Periodicals such as the Baltimore-based American Farmer, began providing “literate Southerners with ‘authoritative’ information about effective hunting methods and ‘proper technique’. The sporting press became a medium through which wealthy white Southerners developed the image of the aristocrat-hunter, or the sportsman, as popular Southern icons.”

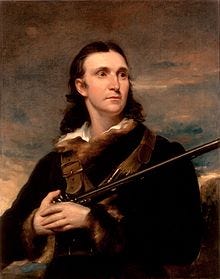

William Elliott (1788-1863) was a third generation South Carolina planter, writer, and sportsman. Elliott had also served in the state senate for two decades, and was respected as “one of the most gifted planters of the Old South” — producing large crops of rice and sea island cotton.

Elliott was also a writer, and frequently wrote on “agricultural and outdoor topics” in popular publications of the day such as the American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine.

In 1846, William Elliott created a collection of his own stories and articles into a book entitled Carolina Sports by Land and Water, Including Incidents of Devil Fishing, Etc., which was “landmark of American sporting literature.”

President Theodore Roosevelt was a fan of Elliott’s book and wrote:

"The charm of these tales lies in the animation and gusto with which Elliott communicates his experiences ... Killing devil-fish with the harpoon and lance had always appealed to me as a fascinating sport, since as a boy I had read Elliott's account of it in his 'Field Sports of South Carolina.”

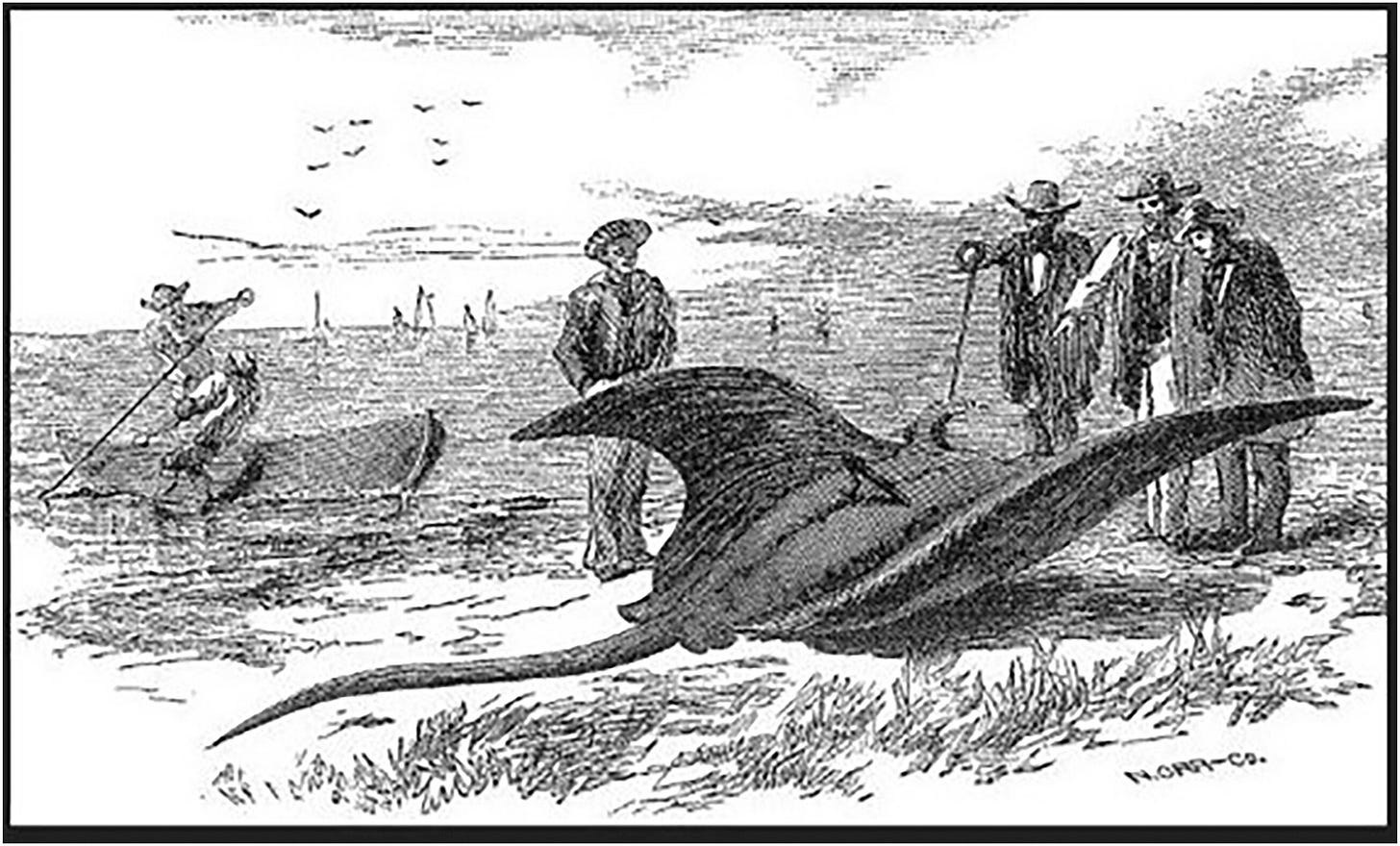

What did Elliott mean by “Incidents of Devil Fishing”?!

Both pre- and post-Civil War, scientists, hunters, and business entrepreneurs in the Carolinas had a fascination with giant manta rays, which they called “devil fish” because of the horn-shaped fins on their head.

According to the International Journal of Maritime History:

“Local fishermen, along with celebrities like the US president, Teddy Roosevelt, harpooned devil fish in Cape Lookout while marveling at their grace and strength, breaching up to six feet above the water's surface. Beaufort planter William Elliott presented many accounts of this fantastic sea creature, with vivid stories of enslaved African harpooners jumping off boats onto the backs of giant manta rays. This research combines historical accounts and images, newspaper advertisements and talks at local explorer clubs to illustrate case studies of the community's obsession with collecting, cooking, hunting and conquering rays as an important component of maritime leisure and environmental history. It concludes by addressing international examples of subsistence, recreational and industrial fishing, and its impacts on manta rays.”

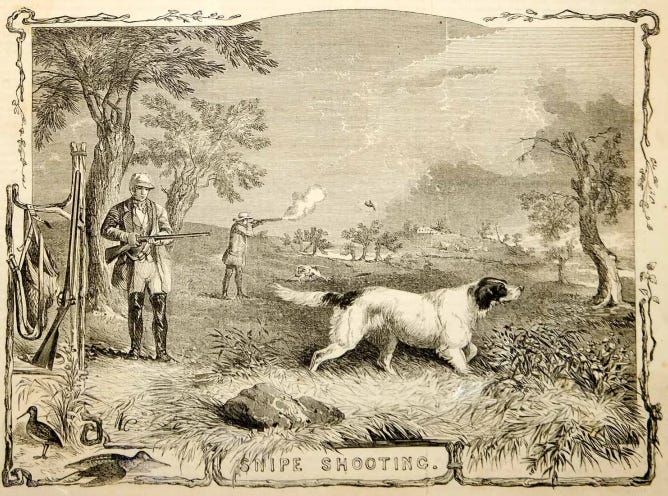

While some (niche) hunters pursued Devil Fish in the ocean, back on land, wealthy planters organized hunts on horseback and pursued live game with firearms.

Nicolas W. Proctor, author of the book Bathed in Blood: Hunting and Mastery in the Old South, writes:

“Defined by their adherence to the rules of sport, sportsmen transformed the hunt from a convenient source of meat and hides into a rarefied form of recreation and public display. In time, the sportsman evolved into a paragon of a particularly Southern vision of white manhood.”

Southern hunters would use their slaves as hunt masters, dog handlers, and assistants.

Enslaved workers were sometimes given permission to hunt for their families, while others hunted in secret.

There was a great cultural difference between the Southern gentry who hunted for sport and the poor, white backwoodsmen who hunted for necessity.

The wealthy would bait their pray with corn or salt licks and would mostly shoot birds “on wing” — and only with a shotgun. Whereas, “yeoman whites” and slaves who depended on hunting for sustenance or income rarely shot birds in flight.

Poor hunters also typically used rifles, which were “more versatile and required less shot and powder” — as a cheaper alternative to a shotgun.

While there was a stark difference in hunting style between the wealthy and the poor, some wealthy Southerners valued yeoman hunters for their knowledge of the land and the wild game within it. Some were hired as hunting guides for the wealthy.

Continued advancements in firearms, the advent of the steam engine and steamboat to transport hunters to wild-life rich areas, and a growing population, “accelerated the exhaustion of wild game.”

In colonial times, white hunters preferred hunting bear and deer, but as these animals declined over the decades, hunters made the slow shift to smaller animals such as wild bird, fox, lynx, and racoon.

Hunting, and general interest in wild birds within the state, also impacted art and culture in the Antebellum period. Though he was never a permanent resident in South Carolina, the famous French-American self-trained artist, naturalist, and ornithologist John James Audobon collaborated with South Carolinians like Maria Marin Bachman (who worked as Audobon’s watercolor assistant) on his famous Birds of America series in the 1830s.

Audubon’s work in Charleston, South Carolina was some of his most productive, and the Holy City looms in the background of Audubon’s work — sometimes quite literally. In his painting below of the long-billed curlew, “blades of sweetgrass and the bill of the migratory bird frame a balmy Charleston landscape at sunset, replete with its famous church steeples.”

The Civil War brought huge economic and social changes to South Carolina, but hunting traditions persisted into the 20th century.

Many planters relocated to the cities, and though they shifted away from using their land for agriculture, they still utilized it for hunting.

After the Civil War, wealthy Northerners became interested in purchasing former plantations in South Carolina’s Low Country as “preserves to hunt deer, quail, and waterfowl.”

From the SCETV “Between the Waters” Project:

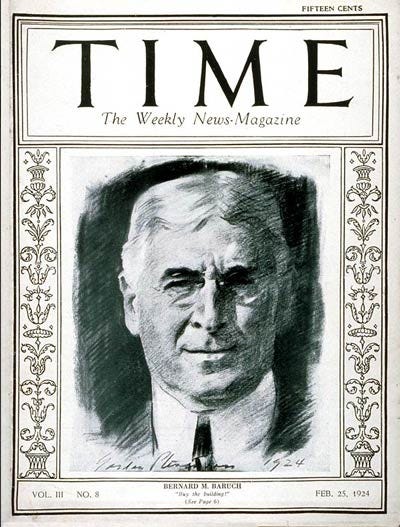

“After the Civil War, the role of hunting and fishing shifted within Southern society. Rice production declined after the war, and disappeared from South Carolina almost entirely by the early twentieth century. The uncultivated rice fields evolved into wetland habitats that attracted huge numbers of migrating waterfowl, and Southern landowners, particularly those in the Lowcountry, leased portions of their property to hunters and hunt clubs. It was during this period that the South emerged as a leading sporting destination for wealthy white Northerners, including Bernard Baruch.”

Bernard Baruch was an American financier and statesman who was originally born in 1870 in Camden, SC to a Jewish family. Interestingly, his father was a physician, Confederate soldier, and member of the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1879, Baruch’s father moved the family from South Carolina to New York City. Bernard Baruch became a young star on Wall Street. As a stockbroker, he amassed a fortune before age 30.

In 1916, Barch left Wall Street to become a top advisor to President Woodrow Wilson. He managed the nation’s “economic mobilization” in World War I and was chairman of the War Industries Board. He advised Wilson during the Paris Peace Conference. In World War II, he became a close advisor to President Roosevelt “on the role of industry in war supply.” Baruch College of the City University of New York was named for him.

To escape his hectic life and responsibilities in New York, Bernard Baruch is a prime example of one of the “wealthy Northerners” who purchased formerly grand Southern plantations in this period.

Baruch was deeply interested in hunting, and “by virtue of his Southern roots” (having been born in Camden, but grew up in New York) was excited to establish a hunting tradition with his family at the plantation he purchased, Hobcaw Barony.

Hobcaw Barony is a 16,000-acre tract of land on a peninsula called Waccamaw Neck. Before the Civil War, this land was home to “about a dozen rice plantations” that contributed to the booming Antebellum economy of Georgetown County.

Bernard Baruch acquired the land in three different purchases from 1905 to 1905 as his winter hunting retreat.

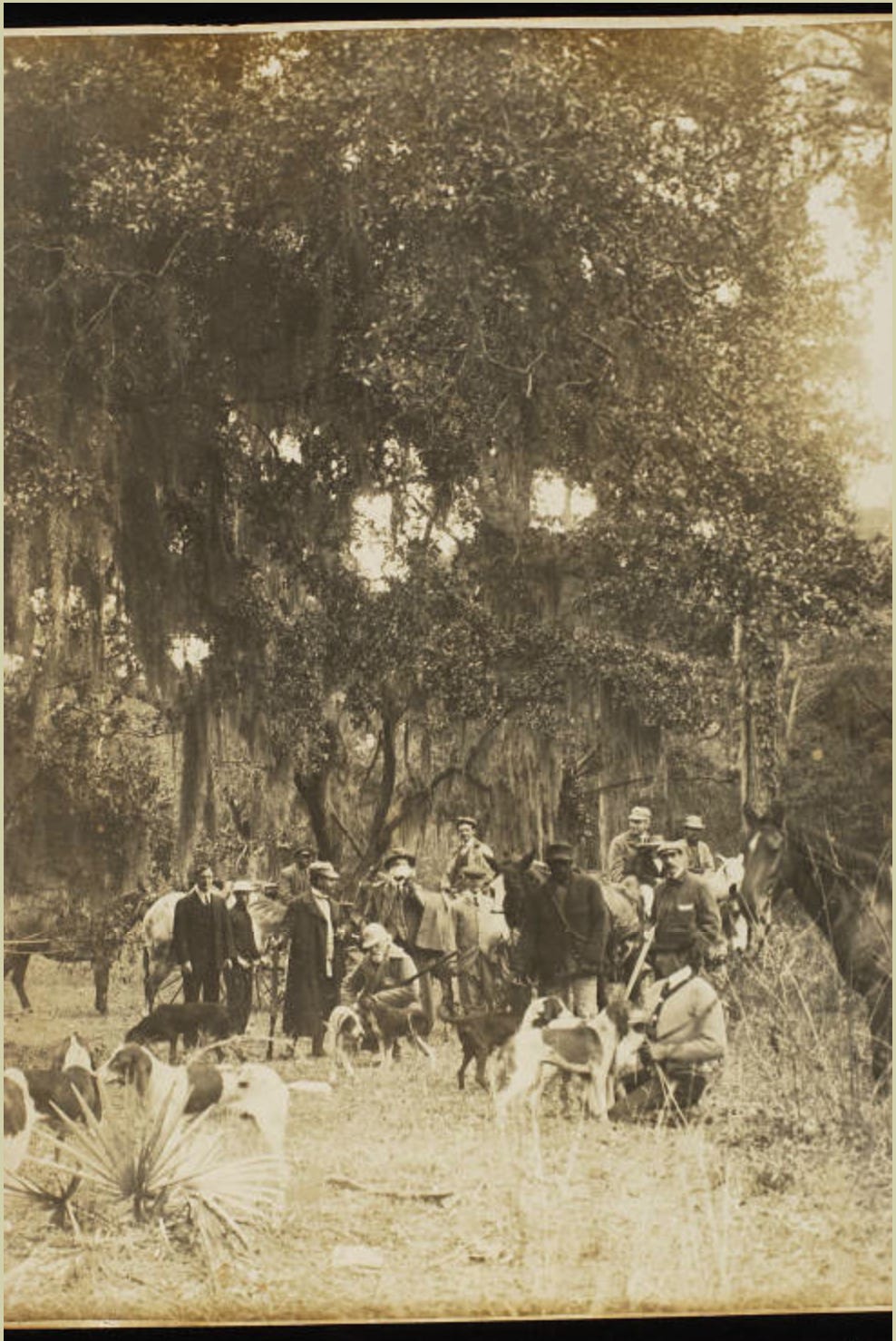

Here is a look into the hunting adventures of the Baruch family and their guests during this period:

“For the next four decades the rich and famous joined Bernard and his family on hunting expeditions at Hobcaw Barony. Baruch employed the African-American residents of the former slave villages within Hobcaw Barony, and the white Caines brothers – former poachers – to serve as hunting guides for him and his guests, completing their Southern experience.

Guests who visited the Baruchs at Hobcaw Barony were treated to extravagant dinner parties, and hunting excursions through Hobcaw’s swamps and rice canals. There are seven Baruch guest books covering the period from December, 1911 through August, 1946. Guests who wrote their names in the books include artist Louis Aston Knight; Robert and Evangeline Johnson, children of Johnson & Johnson founder Robert Wood Johnson; Harry Whitney, wealthy financier, sportsman and husband of Gertrude Vanderbilt; Richard Irvine Manning, Governor of South Carolina from 1915 – 1919; newspaperman Ralph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World and the Evening World; and Herbert Bayard Swope, journalist and member of the Algonquin Round Table. When he visited in 1921, Robert Wood Johnson II wrote in the guest book, “A most marvelously organized shooting lodge. The greatest ducking.”

Throughout the early 20th century, many other prominent and wealthy northerners followed Baruch to the South to establish their own Southern vacation homes and hunting preserves.

In this period, there were also hunting clubs. According to the South Carolina Encyclopedia:

“Working-class whites and blacks created formal and informal hunting clubs especially to pool resources and rent hunting land. Clubs tended to be segregated by race and class and, until recently, usually excluded women.”

The surge in sporting tourism, combined with a rise in unregulated hunting, eventually underscored to Southerners the critical need to protect fish and game.

The national conservation movement “finally infiltrated the South in the mid to late nineteenth century, bringing about regulations on hunting and fishing, and wider conservation practices.”

This new attitude toward conservation would be applied at Bernard Baruch’s Hobcaw Barony to preserve the property’s natural habitat and wild game. In fact, in 1956, Bernard Baruch signed over Hobcaw Barony to his daughter Belle Baruch, who recognized the environmental importance of her family’s land and took legal strides to preserve it.

In 1964, Belle established the Bernard Baruch Foundation Trust mandating that Hobcaw be used, “for the purpose of teaching and/or research in forestry, marine biology, and the care and propagation of wildlife and flora and fauna in South Carolina.”

Today there are two research facilities on the Hobcaw Barony property: Clemson University’s Belle W. Baruch Institute of Coastal Ecology, established in 1968; and the University of South Carolina’s Belle W. Baruch Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences, founded in 1969.

Hobcaw Barony’s 16,000 undeveloped acres remain dedicated to research, education, and the preservation of wildlife habitat.

In the later decades of the 20th century, South Carolina took more measured steps to develop rules and regulations for hunting.

In 1994, the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) was established.

Many nongovernmental organizations now exist to help preserve the hunting traditions of the state and its wildlife — organizations such as Ducks Unlimited and the National Wild Turkey Federation, based in Edgefield.

Competitive hunting in the form of field trials is now popular — as seen at the Grand American, the nation’s largest raccoon-hunting field trial, held annually in Orangeburg.

Hunting remains “remains one of the state’s most important forms of outdoor recreation” and hunters have embraced new technologies into their traditional practices.

Hunt is also “big business” for South Carolina:

“Hunting is a big business in the state, combining the impact of expenditures on arms, clothing, fuel, dogs, new technologies, land leases, and licenses. In 1996 SCDNR reported receipts from hunting licenses purchased by South Carolinians totaled more than $4 million. A further indication of South Carolina’s continued attractiveness to out-of-state hunters is the more than $2.5 million that visiting sportsmen paid for licenses that year.”

Since 1983, South Carolina hosts an annual Southeastern Wildlife Exposition (SEWE) each February that features 500 artists, exhibitors and wildlife experts and 40,000 attendees annually, generating an estimated $50 million in economic impact every year to the state. (Note from Kate: I’d love to go to SEWE this year!)

From the SEWE website:

“SEWE is a celebration of the great outdoors through fine art, live entertainment and special events. It’s where artists, craftsmen, collectors and sporting enthusiasts come together to enjoy the outdoor lifestyle and connect through a shared passion for wildlife. The largest event of its kind in the U.S., SEWE promises attendees unforgettable experiences every February in Charleston, South Carolina.”

We’ll end today’s newsletter on a high note by highlighting hugely popular annual “DockDogs Competition” at the SEWE exposition — where dogs of all breeds and skills compete in “thrilling water jumping contests”! Here is a video:

➳ Sources — The History of Hunting in South Carolina

“Audubon and the Lowcountry.” Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, College of Charleston, https://halsey.cofc.edu/learn-blog/audubon-and-the-lowcountry/. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

"Carolina Sports by Land and Water, Including Incidents of Devil-Fishing." Donald Heald Rare Books, https://www.donaldheald.com/pages/books/35963/william-elliott/carolina-sports-by-land-and-water-including-incidents-of-devil-fishing-c. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

“DockDogs Competitions.” SEWE: Southeastern Wildlife Exposition, https://www.sewe.com/event/dockdogs-competitions-4/. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

“Hobcaw Barony.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobcaw_Barony. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

“Hunting.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/hunting/. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

“The Baroness of Hobcaw: Learn About the Fascinating Life and Legacy of Heiress Belle Baruch.” Hobcaw Barony, https://hobcawbarony.org/the-baroness-of-hobcaw-learn-about-the-fascinating-life-and-legacy-of-heiress-belle-baruch/. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

"The Culture and Tradition of Hunting in the American South: Hunting in the Antebellum South (Part 1)." Making History, 13 Aug. 2016, https://makinghistorybtw.wordpress.com/2016/08/13/the-culture-and-tradition-of-hunting-in-the-american-south-hunting-in-the-antebellum-south-part-1/. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

"The Culture and Tradition of Hunting in the South: Hunting in the New South – Class and Racial Divides and Environmental Conservation (Part II)." Making History, 3 Sept. 2016, https://makinghistorybtw.wordpress.com/2016/09/03/the-culture-and-tradition-of-hunting-in-the-south-hunting-in-the-new-south-class-and-racial-divides-and-environmental-conservation-part-ii/. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

"Why Did They Do It? Motivations for the Southern Hunting Tradition." Journal of American Southern Studies, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/08438714241266441. Accessed 23 Nov. 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!