#125: The Rev. War Battle of Great Cane Brake, Christmas Candlelight Tours, and The Swamp Fox

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, interviews w/ experts, book recommendations, and upcoming SC historical events.

Dear reader,

Welcome to SC History Newsletter #125!

This weekend, I had a fun South Carolina historical adventure!

I was invited to an event at the Historic Hopkins Farm in Simpsonville where the Sons of the American Revolution hosted a commemoration of the Battle of the Great Cane Brake, which is the only Revolutionary War battle ever fought in Greenville County. The battle happened right there on the Historic Hopkins Farm property.

After the ceremony — complete with men and women in historical costumes, muskets, cannons and more! — we all piled into trucks, and even a hayride, to trundle down through the woods to the actual, physical site of the battle! Local historian Durant Ashmore gave both the keynote address at the commemoration ceremony and led us in a tour of the battle site.

After the tour, my chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (Nathanael Greene), led the group in a ceremonial dedication of a Liberty Tree on a hill nearby. The tree planted is an American Elm, just like the original Liberty Tree in Boston during the Revolution. It was an exciting day of “living history” and is the inspiration for the newsletter today, as I explain the history of the Battle of the Great Cane Brake below.

But first, here are some photos for fun!

I look forward to diving into the history of this Revolutionary War Battle below!

Enjoy!

New friends! If you are new to the newsletter, please note that there are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and so much more! I encourage you to take a look at our archive here.

Send me your topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you. :)

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Events

Please note our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered.

Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

Event Recommendation of the Week:

December 14 & 15 | “Christmas Candlelight Tours: Historic Brattonsville” | McConnells, SC | Website

“Join us for an evening of traditional Christmas festivities and a guided candlelit tour, set in 1780, to experience what Christmas may have been like during the American Revolution.

On-going activities:

• Meet Father Christmas

• Make-and-take activities: Candle-dipping and making ‘scherenschnitte’ (German for “scissor cuts”) snowflake ornaments

• Brass band and traditional fiddle music

• Christmas shopping at Historic Brattonsville Gift Shop, Phil Gilson – Glassblower, Zettlemoyer Pottery, and Deadra Johnson – Sweetgrass Basket Weaver.”

➳ SC History Book, Article, & Movie Recommendations

“The Swamp Fox: How Francis Marion Saved the American Revolution” by John Oller

Here is the publisher’s description:

“This comprehensive biography of Francis Marion, the Swamp Fox, covers his famous wartime stories as well as a private side of him that has rarely been explored

In the darkest days of the American Revolution, Francis Marion and his band of militia freedom fighters kept hope alive for the patriot cause during the critical British "southern campaign." Employing insurgent guerrilla tactics that became commonplace in later centuries, Marion and his brigade inflicted enemy losses that were individually small but cumulatively a large drain on British resources and morale.

Although many will remember the stirring adventures of the "Swamp Fox" from the Walt Disney television series of the late 1950s and the fictionalized Marion character played by Mel Gibson in the 2000 film The Patriot, the real Francis Marion bore little resemblance to either of those caricatures. But his exploits were no less heroic as he succeeded, against all odds, in repeatedly foiling the highly trained, better-equipped forces arrayed against him.

In this action-packed biography we meet many colorful characters from the Revolution: Banastre Tarleton, the British cavalry officer who relentlessly pursued Marion over twenty-six miles of swamp, only to call off the chase and declare (per legend) that "the Devil himself could not catch this damned old fox," giving Marion his famous nickname; Thomas Sumter, the bold but rash patriot militia leader whom Marion detested; Lord Cornwallis, the imperious British commander who ordered the hanging of rebels and the destruction of their plantations; "Light-Horse Harry" Lee, the urbane young Continental cavalryman who helped Marion topple critical British outposts in South Carolina; but most of all Francis Marion himself, "the Washington of the South," a man of ruthless determination yet humane character, motivated by what his peers called "the purest patriotism."

In The Swamp Fox, the first major biography of Marion in more than forty years, John Oller compiles striking evidence and brings together much recent learning to provide a fresh look both at Marion, the man, and how he helped save the American Revolution.”

Have you read this book? Tell us your review! Leave a comment below!

➳ SC History Topic of the Week:

The History of The Battle of Great Cane Brake

Did you know that over 200 Revolutionary War battles were fought in South Carolina?

Growing up in New England, it’s interesting to reflect that in my schooling, my teachers always made it seem like the Revolutionary War was centered in Massachusetts and the Northeast. Boston Tea Party, Stamp Act, etc. Of course, battles were fought in all 13 colonies, and now that I live in South Carolina I’m a bit biased — and as the South Carolina 250’s recent marketing campaigns vividly show, “Independence was won in South Carolina.”

This past Saturday, I was thrilled to go to the Historic Hopkins Farm in Simpsonville, SC for a Liberty Tree dedication in honor of the Revolutionary War Battle of Great Cane Brake which happened on December 22, 1775 on this property. This battle was the only Revolutionary War Battle to take place in Greenville County.

This conflict occurred 8 months after the first shots of the Revolutionary War were fired at Lexington and Concord and 8 months before the Declaration of Independence was signed.

December 1775 was a dangerous and uncertain time for the backcountry of South Carolina. The backcountry was divided between the Loyalists (Tories) who wanted to remain faithful to the crown of England, and the Whigs (Patriots) who wanted independence from British control.

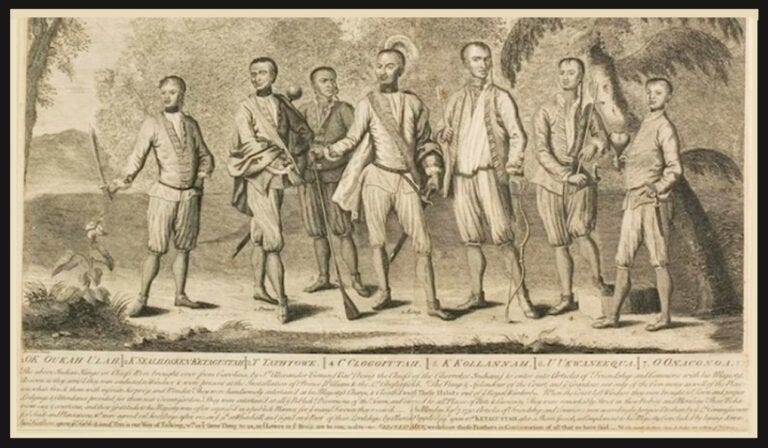

In the backcountry, there was also a third faction also jockeying for power: the Cherokee Indians, who were traditional British allies. The British government in London “curried the favor of the Cherokees by promising them that European expansion would stop at the Appalachian Mountains.”

To further cement the British alliance with the Cherokees, the governor in Charles Town (not yet called Charleston) sent by wagon train “annual disbursements of powder and gunshot for hunting purposes.”

The wagon train of ammunition followed a Cherokee Path (which likely started as an animal game trail), “passing through Ninety-Six and then on to Fort Prince George in Indian Territory.” Fort Prince George was located on the Keowee River across from the Cherokee town of Keowee, the primary town of the Cherokee lower settlements. These sites are now under water, beneath Lake Keowee in present day Oconee County.

In 1775 the 3 western counties of South Carolina — Oconee, Pickens and Greenville — did not exist. This area was referred to as “Indian Territory” on the maps from this period. (Note from Kate: it was exciting to be at the Historic Hopkins Farm on Saturday and understand that the beautiful landscape was formerly “Indian Territory!”)

The Cherokee Territory also included parts of northeast Georgia, western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee.

Despite being thoroughly defeated in the First Cherokee War of 1760, the 6,000 “braves” of the Cherokees remained a formidable fighting force.

The growing tension between these three factions — the Loyalists, the Patriots, and the Cherokees in the backcountry — came to a head in December 1775.

Early action in the Revolutionary War in South Carolina centered around Charles Town. The Royal Governor of South Carolina felt threatened, so he and the members of his government retreated to a British warship in Charles Town harbor.

The resulting void in governance was filled by the Patriot-led “Council of Safety” in Charles Town.

Mentioned above, while the Loyalists and the British Crown wanted to cement their partnership with the Cherokees of the backcountry, the Patriot-led Council of Safety was keenly aware of the strategic importance of a Cherokee tribe. In a power play, the Council of Safety sent their own shipment of shot and powder up north in an effort to the win the Cherokees over to their side.

When the backcountry Loyalists heard about this shipment, they feared the munitions were intended to arm the Cherokees to wage war against them, so the Loyalists planned to seize these armaments for themselves.

Under the leadership of Loyalist Captain Patrick Cunningham, on Oct. 31, 1775 about 70 Loyalists seized the Patriot wagon train of munitions (meant for the Cherokee) at Mine Creek, located about 18 miles south of Ninety-Six.

At this time, the center of British influence in the upcountry was Ninety-Six, which then was a backwoods trading town that had a courthouse and a jail. Any and all legal disputes — either civil or criminal — that occurred in colonial Upstate South Carolina were adjudicated in this backwoods town.

Patriot Major Andrew Williamson thought that the stolen munitions would be found at Ninety-Six, so he organized “a force of 562 men” to retake the shot and gunpowder. This force occupied Ninety-Six, but found no munitions.

In the meantime, Loyalist Major James Robinson organized a force of 1,500 men to surround and besiege Patriot Major Williamson. A standoff occurred. Captain Cunningham was also a member of this Loyalist force.

The first shots of the Revolutionary War south of New England occurred at Ninety-Six on November 19, 1775. One Patriot, James Birmingham, was killed. At James Birmingham’s gravesite the inscription reads “the first South Carolinian to give his life in the cause of freedom”.

Throughout the South Carolina backcountry at this time, loose amalgamations of competing militia forces roamed the countryside.

While Patriot Major Williamson’s 562 men were being besieged by Loyalist Major Robinson’s 1,500 men at Ninety-Six, a Patriot force under the leadership of Colonel Richard Richardson (what a name!) was approaching Ninety-Six with orders to relieve the Patriots.

Colonel Richardson’s force was gaining strength daily, and he commanded a force of 4,000-5,000 men anxious to “throw off the British yoke.”

The first Battle of Ninety-Six ended in a truce before Colonel Richardson’s men arrived on the scene.

Richard Pearis, the first recognized European settler in Greenville County (who settled illegally and had a plantation centered around Greenville’s beautiful waterfall downtown — more on Richard Pearis in SC History Newsletter #55), was a Loyalist captain and a witness to this truce. It was agreed that the Patriots would destroy the fortifications they had constructed and the Loyalists would retreat north across the Saluda River.

The shot and powder sent by the Patriots from Charles Town — that was originally intended for the Cherokees — remained in the hands of Loyalist Patrick Cunningham.

The Patriot-led Council of Safety in Charles Town, along with the Patriots in the backcountry, were highly alarmed that the Loyalists could mount an organized force of 1,500 men to oppose them. They began a campaign to arrest Loyalist leaders. Richard Pearis “was arrested on December 12th, 1775, and spent the next 9 months in chains in a dungeon in Charles Town.”

Thus sets the course of events that were the prelude to what would soon become recognized as the Battle of the Great Cane Brake.

Loyalist Captain Patrick Cunningham planned to take the prized munitions taken from the Patriot forces and “flee into the wild frontier.” Cunningham and about 230 of his men crossed “the dividing line between civilization and lawlessness” and rode into Indian Territory. The area they fled to was dominated by the “vast bottomlands bordering the Reedy River in southern Greenville County.”

Captain Cunningham set up camp in the midst of a huge river cane thicket, referred to as a “canebrake” by early pioneers.

The "canes" were Arundinaria gigantea, a species of large bamboo plants native to the southeastern United States, which before extensive European cultivation, was often found in dense "brakes."

In pioneer times, river bottoms full of river cane dominated thousands of square miles of the southeastern landscape. It was a vital plant for the Native Americans, with an incredible array of purposes. It was used as “lathe for dwellings, basketry, spears, blowguns, fishtraps, flutes, etc.” European agriculture led to the decline of this once dominant landscape feature.

The Reedy River in southern Greenville County is named after river cane. In fact, the canes were so thick along the Reedy that it made the river undesirable for the Cherokees. The banks of the Reedy were so thickly choked it made transportation difficult. What made the Reedy unpopular for the Cherokees made it highly desirable for Patrick Cunningham in this case.

When Captain Cunningham encamped in a canebrake with his Loyalist troops, he knew he was taking a defensive measure that was a long-standing tradition among the Cherokees. Cunningham knew it was impossible to silently approach an enemy through the crackling noise made by fallen river cane leaves.

Likewise, the river cane helped the Patriots locate the Loyalists, who were using the river cane in their campfires. The cane “snapped and popped” when it was burned and “tipped off” the Patriots to the Loyalists’ location.

Patriot Major Williamson was determined to root out Cunningham’s force. He sent a detachment of 1,200 men to follow Cunningham under the direction of Lt. Col. William “Danger” Thomson, a Patriot commander who served with much distinction throughout the war.

What happened next — The Battle of the Great Cane Brake — is described by John Buchanan in his book The Road to Guilford Courthouse:

“After a 23 mile march, in the wee hours of the following day, they [The Patriots] could see Cunningham’s fires about two miles away. Just before daybreak they moved out and attempted to surround the camp. They had almost succeeded when they were discovered. Some Tories fled through a gap in the Rebel lines. Of the 200 about 70 got away, including Patrick Cunningham, who had not even time to saddle a horse but galloped off bareback. According to Rebel sources he called out for everyman to “shift for himself”. The rest were taken prisoner, along with all his baggage, arms and ammunition. The Tories lost five or six killed; the rebels had one wounded.”

Robert D. Bass describes the flight of Patrick Cunningham in his book Ninety Six: the Struggle for the South Carolina Back Country:

“Without taking the time to pull on his breeches, he [Cunningham] sprang astride a bareback horse and galloped off into the land of the Cherokees”.

Thus describes the flight of Patrick Cunningham — “bereft of both saddle and breeches.”

After the Battle of the Cane Brake, the Patriots recaptured the munitions intended for the Cherokee, and took 130 Loyalist prisoners — stripping them of their weapons and their shoes. Patriot Colonel Thomson had to restrain his men from harming the prisoners. However, what would happen next would inflict much pain on the prisoners indeed.

As the Patriots began their long march back to Charles Town with their Loyalist prisoners in tow (who were barefoot) on the Cherokee Road, it began to snow. In fact, it snowed for 30 hours resulting in almost 2 feet of snow. Historian Durant Ashmore explained that this may have been the most snow that has ever fallen in Greenville County. Imagine the suffering of the barefoot Loyalist prisoners, who were likely permanently injured by exposure and frostbite.

Because of this major snowfall in the aftermath of the Battle of the Cane Brake and the other military operations against the Loyalists in the Upcountry November-December 1775, the operation came to be called the “Snow Campaign.”

Today, there is a state historical marker commemorating the Battle of the Great Canebrake on Fork Shoals Rd, at the location of the Historic Hopkins Farm.

The Hopkins Farm is on the National Register of Historic Places. It has been in the Hopkins family for eight generations, going back to 1834. The farm abuts the Reedy River on the western side, and family tradition has commemorated the location of the battle site for over two hundred years.

In 1876, the Hopkins family planted a grove of pecan trees in the bottomland bordering the Reedy in honor of the only battle ever fought in Greenville County. Approximately 25 of these grand trees remain, forming an impressive allee. The Hopkins family named this planting “Patriots’ Grove” in honor of the 100 year anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

It was a very moving experience to visit the battle site. The Reedy River’s bottomland is wide and flat — and you can imagine how, surrounded by the 20-foot tall thick river cane bamboo at the time — this was a perfect setting for the 200 Loyalist men to pitch hidden encampment.

I was able to find some great history of this battle posted by none other than the Canebrake Fire Department. They posted this paragraph about the battle on their Facebook page in 2017:

“The surrounding hills perfectly fit the description by John Buchanan as he described the battle unfolding. Where was Cunningham’s tent, and where was his barebacked horse bridled? Where is the gap through which he escaped? You can almost hear the rifle shots ring out and the full throated cheers and curses as the loyalists forces get routed. Standing in the middle of Patriots’ Grove, it’s impossible to tell from which surrounding hill a deadly musket ball may suddenly thwack you in the back. Patriots Grove reminds one of the sacrifices made so we all can live free.”

The Battle of Cane Brake was significant as a decisive Patriot victory in effectively crippling Loyalist activity in the upcountry region, and “sending a strong message” against supporting the British cause in the region.

➳ Sources — The History of the Battle of Great Cane Brake

"Battle of Cane Brake." Revolutionary War Museum, https://revwarmuseum.weebly.com/battle-of-cane-brake.html. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

"Council of Safety." South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/council-of-safety/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

"Culture in Cloth: Misconceptions Remain About Traditional Apparel for Early Cherokees." Tahlequah Daily Press, https://www.tahlequahdailypress.com/news/culture-in-cloth-misconceptions-remain-about-traditional-apparel-for-early-cherokees/article_c48abfa1-c5f1-53d4-93fe-7bcf5e71f71f.html. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

"Genealogy Research." Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, https://cherokeeofsc.com/geneology-research/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

"How the Reedy River Got Its Name." Greenville Journal, https://greenvillejournal.com/outdoors-recreation/how-the-reedy-river-got-its-name-field-notes-with-dennis-chastain/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

"November 1775: The First Battle of Ninety Six." South Carolina Historical Society, https://schistory.org/november-1775-the-first-battle-of-ninety-six/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

"Richardson, Richard." South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/richardson-richard/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

"Snow Campaign, 1775." American History Central, https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/snow-campaign-1775/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

“Untitled Post from the Canebrake Fire Department.” Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php/?story_fbid=1455547887904477&id=420285624764047. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!

Loved this installment! BTW, Richard Richardson was the namesake of Columbia's Richardson Street from the city's founding in 1786 until around 1892, when it was rechristened Main Street.