#128: The Beautiful Portraits of Henrietta Johnston, The Underground Railroad at Fort Sumter, and Robert Smalls

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, interviews w/ experts, book recommendations, and upcoming SC historical events.

Dear readers,

Welcome to SC History Newsletter #128!

First off, thank you to those who donated towards my birthday fundraiser for Mount Vernon in honor of Ann Pamela Cunningham, our South Carolina heroine and history muse (See SC History Newsletter #22 on “The Lady Who Saved Mount Vernon”). I am pleased to share we surpassed our $500 goal with $565 raised! I am so grateful for your support. It made my birthday really special, and I know George Washington is smiling down on us. :)

I’d like to give a special shoutout to some of our new subscribers — welcome!

nlew

johnsontrina1

lesherdoug

shelleyavella

SCdaytrips

flydogstraining

an.drewcun13

kems322

I hope everyone stayed safe with the snow day we had on Friday. Having grown up in Connecticut (with family roots here in Sumter, SC), I love a good snow day! My stepson (age 12), his neighborhood buddies, and I found the steepest hill in the neighborhood and had a fun session of sledding. With snow being so rare in SC, we had to make the most of it!

Have any fun stories or photos of you/your family in the snow? Please reply to this message and I’ll share in next week’s newsletter!

New friends! If you are new to the newsletter, please note that there are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and so much more! I encourage you to take a look at our archive here.

Send me your comments or topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Have additional ideas or feedback for me? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you. :)

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Events

Please note our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

SC History Event Highlight of the Week:

Saturday, February 15th at 10:00 am | “A Strike for Freedom: The Underground Railroad at Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie” | Fort Moultrie Visitor Center | Sullivan's Island, SC | Website

“The National Park Service is pleased to announce that park staff will host “A Strike for Freedom: The Underground Railroad at Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie” on Saturday, February 15, 2025, at 10:00 am in the Fort Moultrie Visitor Center theater. The event will celebrate the recent inclusion of Forts Sumter and Moultrie into the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program. This is a National Park Service program dedicated to telling stories of those seeking freedom from enslavement.

The event will feature park rangers from Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park and the Network to Freedom program. Visitors will have the opportunity to learn about the Network to Freedom program and hear about the escapes from slavery that qualified the park sites for the program. Immediately following the talks there will be a plaque presentation. At 1:00 pm a park ranger will provide a walking tour of the Fort Moultrie grounds to highlight the harbor paths that enslaved persons traveled to freedom.

The event will begin at the Fort Moultrie Visitor Center on Saturday, February 15, 2025, at 10:00 am. Portions of the event may be recorded and featured in educational materials for the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program. A $10.00 entrance fee is required for adults 16 and over to enter the park; military veterans and visitors with an America the Beautiful pass receive free entry.”

➳ Other SC History Recommendations

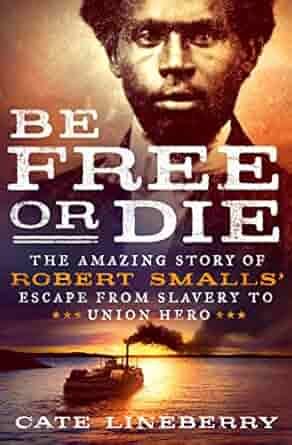

BOOK: “Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls' Escape from Slavery to Union Hero” by Cate Lineberry

Publishers’ description:

“Finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

Henry Louis Gates, Jr: "A stunning tale of a little-known figure in history."

Candice Millard: “Be Free or Die makes you want to stand up and cheer.”

The astonishing true story of Robert Smalls’ amazing journey from slave to Union hero and ultimately United States Congressman.

It was a mild May morning in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1862, the second year of the Civil War, when a twenty-three-year-old slave named Robert Smalls did the unthinkable and boldly seized a Confederate steamer. With his wife and two young children hidden on board, Smalls and a small crew ran a gauntlet of heavily armed fortifications in Charleston Harbor and delivered the valuable vessel and the massive guns it carried to nearby Union forces. To be unsuccessful was a death sentence for all. Smalls’ courageous and ingenious act freed him and his family from slavery and immediately made him a Union hero while simultaneously challenging much of the country’s view of what African Americans were willing to do to gain their freedom.

After his escape, Smalls served in numerous naval campaigns off Charleston as a civilian boat pilot and eventually became the first black captain of an Army ship. In a particularly poignant moment Smalls even bought the home that he and his mother had once served in as house slaves.

Cate Lineberry's Be Free or Die is a compelling narrative that illuminates Robert Smalls’ amazing journey from slave to Union hero and ultimately United States Congressman. This captivating tale of a valuable figure in American history gives fascinating insight into the country's first efforts to help newly freed slaves while also illustrating the many struggles and achievements of African Americans during the Civil War.”

Have you read this book before? Tell us your review! Leave a comment below!

➳ SC History Topic of the Week:

Did you know that Henrietta Johnston was the first professional female artist in Colonial America, and was based in Charleston?

Yes, it’s true! Historians believe that Henrietta Johnston was the first professional female artist to pursue a career in colonial America and has been called “the first portraitist of the American South.” She lived, and started her career, in Charles Towne during the Colonial Era. Today, we will learn about Henrietta and admire some of her beautiful portraits.

Henrietta Johnston was born in Rennes, France around the year 1674 to a Huguenot family. In 1687, her family fled France for London to escape religious persecution.1

In 1694, Henrietta married the son of a baronet and moved to Ireland. While in Ireland, historians believe she learned to make pastel portraits.

Henrietta’s first husband died in 1704, leaving her a widow with 2 young children. She remarried in 1705 to Reverand Gideon Johnston in Dublin, Ireland. Johnston had 4 children, as well as financial troubles.

In 1707, Reverand Johnston accepted the role of the “Bishop of London’s Commissary in Charles Towne” and thus, the Johnston family immigrated to America.

They arrived in Charles Towne in 1708, and life there was not easy. Their family was beset with poverty, illness, and challenging circumstances. A rival pastor had installed himself and refused to give up his post, and Reverand Johnston contracted malaria.2

Henrietta served as her husband’s secretary while keeping the house and caring for the children. She also supplemented their meager income by creating portraits of wealthy and prominent colonists. Thus began Henrietta’s artistic career in America.

Reverend Johnston acknowledged his wife's contributions to their survival when he wrote in a 1709 letter, "Were it not for the assistance my wife gives me by drawing pictures . . . I shou'd not have been able to live."3

According to the New York Historical Society, Henrietta Johnston was “the first colonial artist to use pastels.”

Henrietta Johnston’s style is simple and unadorned compared to the pastels that were being created in Europe, and her subjects wore simpler clothing. Some suggest the simplicity of her artworks was intended to “use less of her precious pastels, which had to be shipped from England.”4

Henrietta’s portraits were also small — generally 9 x 12 inches — and were done in pastels, which at the time was a new material “not in widespread use.”

Below are two of Henrietta’s earliest portraits, of Pierre Bacot and his wife, Marianne Fleur Du Gue.

The Pierre Bacot portrait is housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the portrait of Marianne Fleur Du Gue is housed at the New York Historical Society. From the MET’s website:

“The pastels of the Bacots were among the first that Johnston executed in Charleston, South Carolina, just following her arrival there from Dublin. The artist rendered the Bacots’ facial features with precision and blended colors, particularly in the hair, as she had done in Ireland. Pierre Bacot, also called Peter, was born in Tours, France, in 1684 and was brought by his family to South Carolina as an infant. After his father’s death in 1702, Bacot moved to Goose Creek, where he bought and sold land for a living. He married Marianne Fleur Du Gue sometime after 1705.”

In 1711, Henrietta returned to England “to acquire more pastels and paper.”

Soon after Henrietta’s return to South Carolina, her husband Reverand Johnston left for England himself on business matters. When he returned in 1715, he “found that his wife and other members of his parsonage were sheltered in place due to fighting between the Yamasee people and European colonizers.” (wow!)

About 40 of Henrietta’s portraits are known to exist and were likely created between 1707 and 1720.

Among her earliest Charleston works are also portraits of fellow Huguenots, including portraits of the Du Bose family, with the beautiful portraits of Marie Du Bose and Anne DuBose below.

In 1711, Henrietta painted this remarkable portrait of an 11-year-old Henriette Charlotte Chastaigner (1700-1754), also from a Charleston Huguenot family — who would later become Mrs. Nathaniel Broughton of Mulberry, “a plantation on the Cooper River in Berkeley County that had served as a shelter to other planters during the Yamasee War.”5

When Henrietta’s husband died “in a boat accident” in 1716, Henrietta became the sole provider for her family. She continued to build her artistic career, and her reputation spread.

Here is a portrait below of Colonel William Rhett of Charleston, who was a Colonel in the Provincial Militia and Vice-Admiral in the Colonial Navy. He is best known for “his successful capture of the notorious pirate Stede Bonnet in 1718.” He also held appointments as Surveyor and Comptroller General for His Majesty's Customs and was Lieutenant-General and Constructor of Fortifications.6

In 1725, Henrietta even traveled north to New York to paint portraits of prominent families. Here is a portrait of Anna Cuyler Van Schaik, who was married to a businessman in Albany, New York.7

While the circumstances of her death are unknown, Henrietta Johnston died in Charles Towne on March 9, 1729.

I was sadly unable to find any direct quotations or diary entries from Henrietta Johnston to illuminate us about her personality. However, the fact that she had the grit and the talent to leverage her artistic skills and become the breadwinner for her family — and to pursue a career that no other woman had in the Colonies — I believe shows us that Henrietta Johnston was a woman of grit, grace, and courage. I think we can also surmise that because of her many artistic commissions, that she worked well with her patrons and her good reputation proceeded her.

Today, Henrietta Johnston’s works are housed at the Gibbes Museum of Art (Charleston), the Greenville County Museum of Art (Greenville, SC), the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (Winston-Salem, NC), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City).

Have you seen any of Henrietta Johnston’s portraits at the museums above? Please share below!

➳ Sources — Henrietta Johnston

"Anna Cuyler Van Schaick." Colonial Albany Social History Project, New York State Museum, exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov/albany/bios/c/annacuyler367.html. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

“Henrietta Charlotte Chastaigner.” History of SC Slide Collection, Knowitall.org, www.knowitall.org/photo/henriette-charlotte-chastaigner-history-sc-slide-collection. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

“Henrietta Johnston.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, www.britannica.com/biography/Henrietta-Johnston. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

“Henrietta Johnston: Pastellist Pioneer.” Charleston Magazine, charlestonmag.com/features/ladies_first?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

Johnston, Henrietta. “Henrietta Johnston's Portraits of Early America.” Gibbes Museum of Art, gibbesmuseum.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/204A60AF-F18D-4B51-A13B-671665721310. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

Jeffares, Neil. “Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800: Henrietta Johnston.” Pastellists.com, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/Johnston.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

“Professional Portraitist.” Women & the American Story, New-York Historical Society, wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/professional-portraitist/. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

“Space of Their Own: Henrietta Johnston.” Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, artmusem.sitehost.iu.edu/space-of-their-own/artists/68. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!

Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University. "Space of Their Own: Henrietta Johnston." Eskenazi Museum of Art. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025. https://artmusem.sitehost.iu.edu/space-of-their-own/artists/68.

Ibid.

Gibbes Museum of Art. "Henrietta Johnston's Portraits of Early America." Gibbes Museum of Art. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025. https://gibbesmuseum.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/204A60AF-F18D-4B51-A13B-671665721310.

New-York Historical Society. "Professional Portraitist." Women & the American Story. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025. https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/professional-portraitist/.

"Henrietta Charlotte Chastaigner." History of SC Slide Collection, Knowitall.org. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025. https://www.knowitall.org/photo/henriette-charlotte-chastaigner-history-sc-slide-collection.

Gibbes Museum of Art. "Henrietta Johnston Miniature Collection Detail." Gibbes Museum of Art. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025. https://www.gibbesmuseum.org/miniatures/collection/detail/200DCECE-FFC1-4604-8323-528302244734.

New York State Museum. "Anna Cuyler Van Schaick." Colonial Albany Social History Project. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025. https://exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov/albany/bios/c/annacuyler367.html.