#32: The "Southern Paul Revere," the Cherokee Nation, and the SC Historical Society's annual meeting

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #32 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

Welcome “unccdeanalee3” “beccabarre” “eweberbtn” “cghipp” and “jbritton.sc” to our SC History Newsletter community! Woohoo!

THANK YOU as well for everyone’s feedback on the changes to the newsletter! Based on your feedback, I have decided to keep one (1) featured event at the top of each history newsletter, and will put the rest of the events in a separate weekly email, like I tested out this week. I will also continue to keep two (2) history essays in each history email.

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, March 16th from 11:00 am - 2:00 pm | “The South Carolina Historical Society’s Annual Meeting” | Charleston, SC | TICKETS: $74 for SCHS members, $85 nonmembers

“Join us at Charles Towne Landing State Historic Site for the Society’s 169th Annual Meeting! The day's events include a business meeting, mimosa social, and luncheon featuring this year's keynote speaker Elizabeth Chew, Ph.D., the Society's new CEO.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Do you know that Francis Salvador was the first Jew to be elected to public office in the New World — and for his 28-mile ride to warn his neighbors of danger on the South Carolina frontier, he became known as the “Southern Paul Revere”?

(Note from Kate: After researching Francis Salvador in SC History Newsletter #30 — and the account of his harrowing death — I knew I had to know more!)

While he would end his life in South Carolina, Francis Salvador (1747-1776) was born in London. His family was a part of a Spanish and Portuguese Jewish (Sephardic) community that had developed there since the 17th century. He was raised in wealth and tutored privately at home. Unfortunately, his father Jacob died when Francis was just 2 years old. When Francis came of age, he inherited a large sum of money, and went into business with his uncle Joseph Salvador, who was a “prominent business man” and investor in the British East India Company. Francis and his uncle Joseph partnered with the DaCosta family of London (also of Jewish-Portuguese ancestry) on plans to settle “poor Jews and their family members in the New World.”

Francis married his first cousin, Sarah Salvador (his uncle Joseph’s daughter), and they had a son and 3 daughters before Francis emigrated in late 1773 to South Carolina.

As you may recall from our SC History Newsletter #30, the Sephardic Jewish community in the New World originally emigrated to Savannah, Georgia in 1733 with the first English settlers. When the Spanish attacked Georgia, the Jewish settlers were terrified of religious persecution and fled to Charleston.

As the Jewish community grew in South Carolina, back in London, the Salvador and DaCosta families joined forced financially to buy 200,000 acres (Note from Kate: 200,000 acres is the size of Barbados x 2!) in the new district of Ninety-Six on the western frontier of the Carolina colony. The families began to settle their land.

Francis acquired 7,000 of those acres for his family and arrived in Charleston in 1773. Francis emigrated alone and intended to send for his wife and children in London “as soon as he was able.” Francis bought enslaved Africans to work his land and settled at Coroneka (also called Cornacre) in 1774. He was living on — what was essentially — the frontier of South Carolina.

As Francis began to build his life and plantation in Coroneka and in Charleston, he became “close friends” with the the rising leaders of the Revolution in the South, including Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, John Rutledge, William Henry Drayton, Henry Laurens, and Samuel Hammond. As a testament to his impact and connections in the local community, Francis became the first Jewish elected official in the New World when he was elected as a delegate to South Carolina’s Provincial Congress, and then re-elected in 1775 — a post he held until his untimely death.

At the first Provincial Congress in Charleston in January 1775, Francis was chosen for important committee assignments including “drawing up the declaration of the purpose of the congress to the people; obtaining ammunition; assessing the safety of the frontier, and working on the new state constitution.”

At the second Provincial Congress in November 1775, Francis was a “champion for independence” and he urged his fellow delegates to instruct the colony's delegation to the Continental Congress to cast their vote for independence. Salvador also chaired the Ways and Means Committee of this second Provincial Congress, at the same time serving on a select committee authorized to issue bills of credit as payment to members of the militia.

Meanwhile, back at Francis’s plantation — out on the frontier — dangerous activities began to unfold. On July 1, 1776, Cherokee Indians began attacking frontier families in the Nine-Six District. Sounding the alarm, Salvador rode 28 miles by horse from his lands to the White Hall plantation of Major Andrew Williamson. This ride earned Francis the nickname the “Southern Paul Revere.”

On July 31, 1776, Major Williamson led a 330-men militia, including Francis Salvador, into an ambush orchestrated by the enemy Tories and their Cherokee allies at the Keowee River. As we learned the other day, poor Francis was shot by the enemy, fell into the bushes, and was later found by the Cherokee and scalped.

For those of you who weren’t able to read our historic quote of the account of his death, written by Colonel William Thompson, I believe it’s worth re-pasting here:

Here, Mr. Salvador received three wounds; and, fell by my side. . . . I desired [Lieutenant Farar], to take care of Mr. Salvador; but, before he could find him in the dark, the enemy unfortunately got his scalp: which, was the only one taken. . . . He died, about half after two o'clock in the morning: forty-five minutes after he received the wounds, sensible to the last. When I came up to him, after dislodging the enemy, and speaking to him, he asked, whether I had beat the enemy? I told him yes. He said he was glad of it, and shook me by the hand – and bade me farewell – and said, he would die in a few minutes.

Alas, Francis died from his wounds at the age of 29. He was the first Jew to die in the Revolutionary War. He would never have the opportunity to bring over his wife and children to the New World. They remained in London.

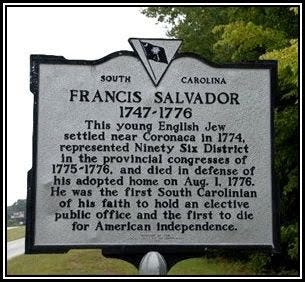

I sadly could not find any historical portraits or images of Francis Salvador (I’ll let you know if/when I do), but here is an SC historical marker, located in Greenwood, SC, and dedicated to him in 1960 by the Jewish Citizens of Greenwood.

II.

Did you know the Cherokee were one of the largest and most powerful Indian Nations the early Carolina settlers had contact with?

(Note that I consulted the website of the Museum of the American Indian, which confirmed that the terms “American Indian, Indian, Native American, or Native are acceptable and often used interchangeably in the United States.”)

From the account of Francis Salvador above, I wanted to also shed light on the Cherokee Indian Nation, who were one of the largest and most powerful Indian groups the Carolina colonists had contact with.

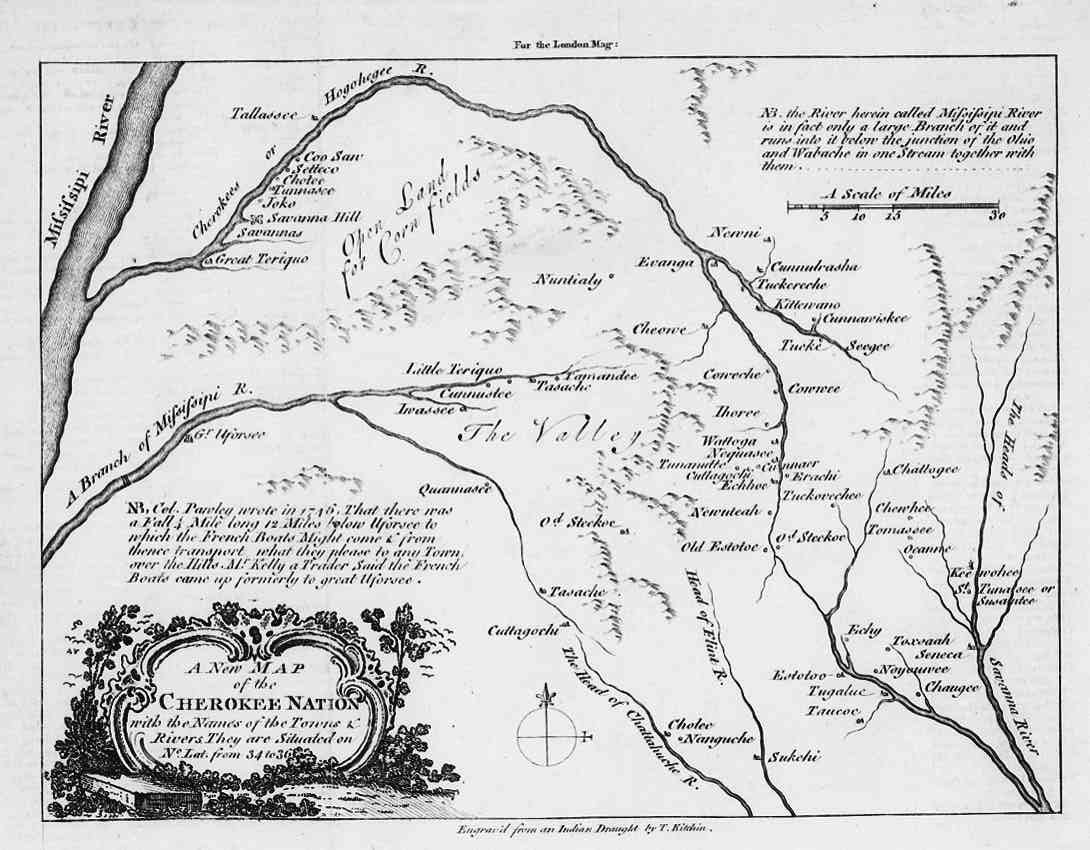

Cherokee arrived in the southeastern United States around 1400 BC, leaving the Great Lakes after conflicts with the Iroquois and Delawares. At the time of European contact, the Cherokee’s sphere of influence “encompassed most of northwestern South Carolina and stretched north and west to the Ohio River to include most of Kentucky and Tennessee as well as parts of West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. By the mid–seventeenth century, Cherokee settlements in South Carolina, known as the lower towns, included Seneca, Keowee, Toxaway, and Jocassee.”

The Cherokee were an agricultural people, which allowed for them to establish a stable network of towns throughout the Appalachians. Many of these towns were accessible over river via canoe and thus, the Cherokee created a thriving network of trade. While Cherokee men handled trade and hunting, the Cherokee women led their towns’ efforts in agriculture, with corn being the primary crop.

European settlers came into contact with the Cherokee soon after establishing permanent settlements on the South Carolina Coast. During the Yemassee War (a subject for a whole separate newsletter!), some Cherokee fought on the side of the Charleston settlers, while other Cherokee simply didn’t trust the colonists. After the Yemassee War, Carolina-Cherokee trade became easier.

In 1730, Sir Alexander Cuming took a “small delegation of Cherokees to London to cement a recent allegiance to King George II.” The Cherokee were presented at court on June 18, 1830 and they were described as:

“naked, except an Apron about their middles, and a Horse’s Tail hung down behind; their Faces, shoulders &c. were painted and spotted with red, blue, and green etc.”

Allegiances continued to shift between the Cherokee and the various Spanish, French, and English settlers in the Southeast. A skirmish between the Carolina settlers and the Cherokee at Fort Prince George further ignited tensions. A fragile peace was established in 1761, but the Revolutionary War brought a whole new set of challenges.

In 1765, three Cherokee chiefs accompanied Henry Timberlake, a British colonial officer to London to meet the Crown and “strengthen a newly declared peace.” The illustration below is a depiction of this encounter.

During the Revolutionary War, the Cherokee mostly sided with the British. Tensions between the Cherokee and the colonists escalated to new heights when the Cherokee attacked colonists in the Holston River Valley in northeastern Tennessee — the colonists were technically settled on Cherokee lands. After this Cherokee attack, a “multicolony army” banded together to retaliate and destroyed 6,000 bushels of Cherokee corn, while the South Carolina government paid the army a “bounty for Cherokee scalps.” This full-scale assault effectively ended Cherokee participation in the Revolutionary War, and in 1777 the Cherokees ceded most of their South Carolina land. The Cherokees acknowledged the United States in the Treaty of Hopewell in 1785, signed near present-day Seneca. On March 22, 1816, the Cherokees ceded their last strip of land in South Carolina.

While their Cherokee brethren were forced to relocate to western reservations between 1816-1840 on the horrific Trail of Tears, South Carolina did not force the Cherokee to relocate. Many of the Cherokee bought land from the state after the 1816 treaty, mostly in the Golden Corner, an area of the Low Country in the far southern corner of South Carolina.

Today, there is no federally recognized Cherokee Nation or tribe in South Carolina, but their heritage and influence remains. (Note from Kate: I was not able to find a percentage of South Carolinians who claim Cherokee heritage, but I will continue to look). Please note that we have a Museum of the Cherokee in Walhalla, Oconee County. Cherokee names remain on well known South Carolina towns including Seneca (“people of the standing rock”), Keowee (“place of mulberries”), Toxaway (“land of the red bird”, and Jocassee (“place of the lost one”).

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

I.

“Born an aristocrat, he became a democrat;

An Englishman, he cast his lot with the Americans;

True to his ancient faith, he gave his life;

For new hopes of human liberty and understanding.”

— In 1950, to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Charleston's Jewish congregation, the City of Charleston erected a memorial to Francis Salvador, the first Jew to die for the American Revolution

Sources used in today’s newsletter:

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!