#92: History of Camden, Carpetbaggers & Scalawags, and Pirates Take Charlestown!

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #92 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

angiedjones1972

h-edwards3

dwpolk82

mandydavidson

chrishorn1125

coby.bland

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, June 1st at 10:00 am - 3:00 pm | “Pirates Take Charlestown” | Powder Magazine Museum | Charleston, SC | Admission fees apply

“The Powder Magazine Museum and the Old Exchange Building are teaming up to showcase Charleston’s pirate history on Saturday, June 1st, with a PIRATE ENCAMPMENT, ARREST, and TRIAL! Join us to learn more about the impact piracy had on early Carolina and upon Charleston in particular.

Beginning at 10:00AM, pirates will overtake the Powder Magazine Museum (79 Cumberland Street)! Sea rovers from the Charles Revenge and the Charles Towne Few will make camp in the front cannon yard. These reenactors will demonstrate nautical crafts in a living history program that will be fun for the entire family!

Around 3:00PM, Redcoats will arrest the pirate crews and march them through the streets of Charleston to the Old Exchange Building (122 East Bay Street), where they will stand trial for piracy on the high seas. Help decide their fate during an interactive mock trial at 3:30PM at the Old Exchange Building!

Admission to the Powder Magazine Museum is $8 for adults, $7 for military/seniors, $5 for children ages 7-15, and free for children under 7 years old. Admission to the Old Exchange Building is $15 for adults, $8 for children ages 7-12, and free for children under 7 years old.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

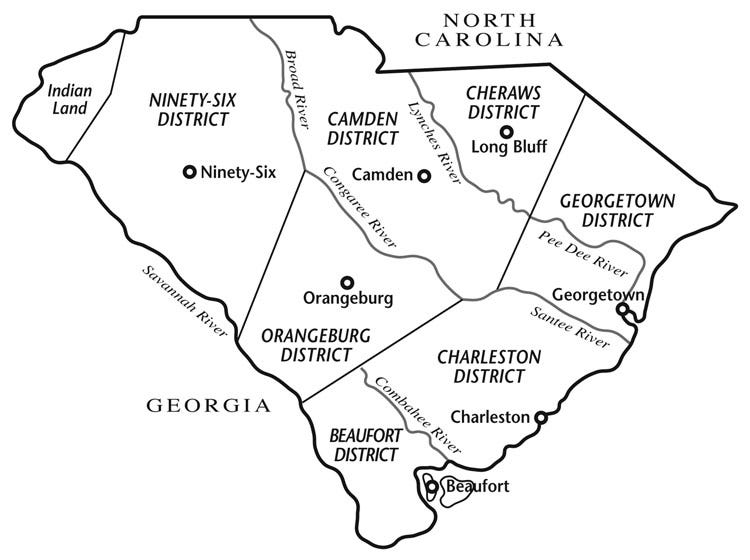

Did you know that Camden was the earliest permanent inland settlement in South Carolina?

(Note from Kate: Thanks to our friend and subscriber for this recommendation that I delve into the history of Camden, SC today. Also, check out his Substack page on all things University of South Carolina athletics: South By Southeast - A Gamecock Odyssey.)

Located in the Midlands, Camden boasts more than 60 well-preserved buildings in its historic district that attest to its past that is rich with great history.

Settlement of Camden evolved from instructions by King George II in 1730 to locate a backcountry township on the Wateree River.

The settlement of the Camden area started with Fredericksburg, which had been laid out in 1733 and 1734 on swampland. The area proved uninhabitable, and immigrants soon dispersed into the surrounding countryside.

About 1750 a colony of Irish Quakers settled on scattered plantations and befriended Catawba Indians of the area.

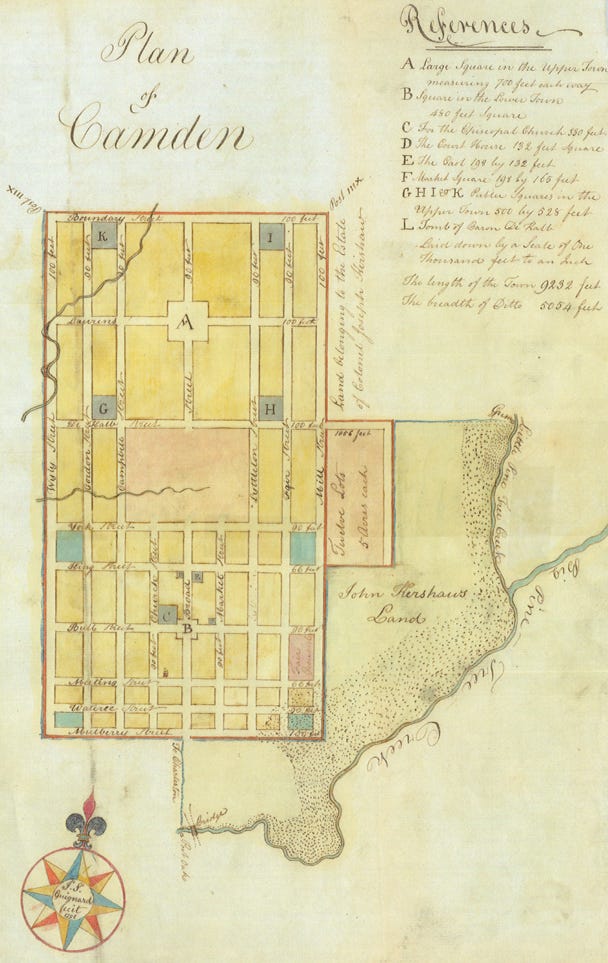

In 1758, Joseph Kershaw, the “father of Camden,” established a store on Pinetree Creek, a Wateree tributary. Located on the path between Charleston and the Catawba Nation, Kershaw’s store was “a convenient place to collect and process local produce, especially wheat, before it was forwarded to Charleston.”

The village was named Pine Tree Hill, and it developed into a milling and trading center.

Within a decade the thriving settlement was renamed in honor of the English chief justice Charles Pratt, the 1st Earl of Camden. (Side note: Pratt lived from 1714-1794. He was a champion of colonial rights, and he opposed the British government’s North American colonial policy of taxation without parliamentary representation. In his first speech in the House of Lords (1765), Camden attacked the Stamp Act, one of the colonists’ grievances that led to the American Revolution. His continued opposition to the colonial taxation policy resulted in his dismissal as lord chancellor!)

In 1791 Camden was the second town in the state to be incorporated by the SC General Assembly, and a formal plan was drawn up to guide development.

During the Revolutionary War, British troops under Lord Cornwallis occupied Camden for nearly a year during their campaign to subdue the backcountry.

The “father of Camden” Joseph Kershaw’s home was seized by Cornwallis and used as a supply post, and the British troops remained for 11 months. Lord Francis Rawdon continued occupation of the home the following year, using it for his headquarters.

Among those imprisoned by the British in the Camden jail was the young Andrew Jackson.

Two major Revolutionary War battles were fought near the town: the Battle of Camden on August 15–16, 1780 (as discussed in SC History Newsletter #89), which saw a disastrous American defeat; and the Battle of Hobkirk Hill on April 25, 1781, in which the victorious British “suffered such heavy casualties that they withdrew from Camden a few weeks later.”

The evacuating British destroyed much of the town, including its jail, flour mills, and several private homes. But Camden recovered quickly. A series of fires in following years redirected growth northward from the old town center.

Prosperity increased as the area’s plantation economy grew, “based on cotton and slave labor.”

Anxiety arose briefly among the white population in July 1816 when an alleged slave insurrection was uncovered. 17 slaves were arrested and tried as ringleaders in the conspiracy, 5 of whom were convicted and executed.

Besides free whites and African slaves, there was also a sizable free black community in Camden by 1830.

The prosperous town entertained George Washington in 1791 and the Marquis de Lafayette in 1825.

While in Camden in 1791, George Washington wrote that it was “a small place with appearances of some new buildings” that was “much injured by the British whilst in their possession.”

Marquis de Lafayette came to Camden on his 1824-1825 tour of the United States. On March 9, 1825, he ceremoniously laid the cornerstone to the Baron DeKalb Monument. Baron DeKalb had been a dear friend of the Marquis. He was mortally wounded at the Revolutionary Battle of Camden some 45 years prior. Here is a fun video of a reenactment of Marquis de Lafayette honoring the memory of DeKalb from Historic Camden’s Facebook page.

Meanwhile, Camden continued to grow. The Bank of Camden was organized in 1822, and a branch of the South Carolina Railroad reached Camden in 1848.

The Civil War halted economic prosperity as Camden’s “leading citizenry embraced the Confederate cause.”

The town experienced invasion twice in 1865, first by a detachment of General William T. Sherman’s men in February, then by troops under General Edward E. Potter in April. Public buildings, the depots, and the Wateree bridge were destroyed, as was much private property.

The town was garrisoned by Federal troops for 9 months after the close of the war.

In 1876, the first local public school for African American children was built on a square of town property.

In 1880, northern missionaries established Browning Home, a private school for the children of freedmen. The school became Boylan-Haven-Mather Academy and was open until the mid–twentieth century.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Camden possessed 3 railroad lines, and 2 textile factories at the edge of town attracted workers from impoverished farms.

A graded public school system was soon inaugurated in both white and black schools.

The Camden Town Council coordinated programs to “vaccinate citizens, pave streets, and expand water and light services.”

In 1913 the Camden Hospital opened, thanks in part to the Wall Street financier and native son to Camden Bernard M. Baruch, whose donation to the project was made in memory of his father, a former Camden physician.

In 1915 a Carnegie grant made possible a handsome public library building, which later housed the Camden Archives and Museum.

Starting in the 1880s, another “northern invasion” occurred when the area’s mild winters lured northern visitors to Camden first as a health retreat and then “as a tourist resort and a sports mecca.”

Three grand hotels and numerous smaller establishments catered to affluent guests. Although the hotel era ended with World War II, its effects lingered.

Tourists renovated antebellum homes and became seasonal or permanent residents, thereby helping to preserve the distinctive architecture of Camden.

Golf and polo were introduced to entertain tourists. Equestrian interest “evolved into a multimillion-dollar industry.” The Carolina Cup steeplechase, begun in 1930 at the Springdale Race Course, became an annual spring event. The Colonial Cup, an international steeplechase held in the fall, was inaugurated in 1970 on the same course.

Depressed economic conditions in textiles and agriculture in the 1920s and 1930s had a negative effect on much of the Camden populace.

The onset of World War II brought many changes. In 1941 a school for pilots opened adjacent to the Camden airport, and both British and American airmen received flight instruction there. The facilities of Southern Aviation School afterward became the home of the Camden Military Academy, a private secondary school, while an updated Woodward Field continued airport operations.

After the war, home building expanded and job opportunities increased, especially after 1950 when the opening of a Dupont plant nearby spurred industrialization.

Citizens also worked to improve cultural and recreational opportunities. The Camden and Kershaw County Fine Arts Center united the talents of citizens into a variety of cultural activities, while 178 acres of city parks provided year-round recreation.

In association with the National Park Service, Historic Camden opened on the site of the original town. The Kershaw-Cornwallis House is the centerpiece for the 107-acre living history site where the annual Revolutionary War Field Days reenactment is held each year. The site also features many smaller homes sup up as “miniature museums.” See their website here.

Community leaders continue to focus on “economic development to build a modern city, while remaining respectful of its past.”

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

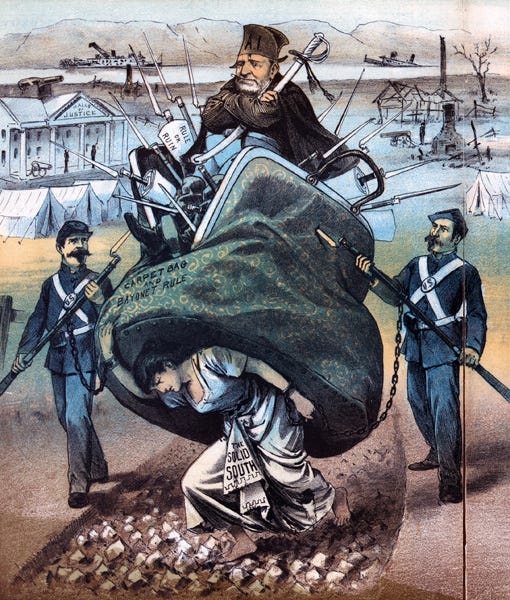

In the aftermath of the Civil War, who were the people referred to as Carpetbaggers and Scalawags?

During and immediately after the Civil War, many northerners headed to the southern states, “driven by hopes of economic gain, a desire to work on behalf of the newly emancipated enslaved people or a combination of both.”

These “carpetbaggers”—whom many in the South viewed as opportunists looking to exploit and profit from the region’s misfortunes—supported the Republican Party, and would play a central role in shaping new southern governments during Reconstruction.

In addition to carpetbaggers and freed African Americans, the majority of Republican support in the South came from white southerners who, for various reasons, saw more of an advantage in backing the policies of Reconstruction than in opposing them. Critics referred derisively to these southerners as “scalawags.”

In the two years following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and the end of the Civil War in April 1865, Lincoln’s successor Andrew Johnson angered many northerners and Republican members of Congress with his conciliatory policies towards the defeated South. Freed African Americans had no role in politics, and the new southern legislatures even passed “black codes” restricting their freedom and forcing them into repressive labor situations, a development they strongly resisted.

In the congressional elections of 1866, northern voters rejected Johnson’s view of Reconstruction and handed a major victory to the so-called Radical Republicans, who now took control of Reconstruction.

Congress’ passage of the Reconstruction Acts of 1867 marked the beginning of the “Radical Reconstruction period,” which would last for the next decade. That legislation “divided the South into five military districts and outlined how new state governments based on universal (male) suffrage—for both whites and Blacks—were to be organized.”

The new state legislatures formed in 1867-69 reflected the revolutionary changes brought about by the Civil War and emancipation: “for the first time, Blacks and whites stood together in political life.”

In general, the southern state governments formed during this period of Reconstruction represented a coalition of African Americans, recently arrived northern whites (“carpetbaggers”) and southern white Republicans (“scalawags”).

More about Carpetbaggers…

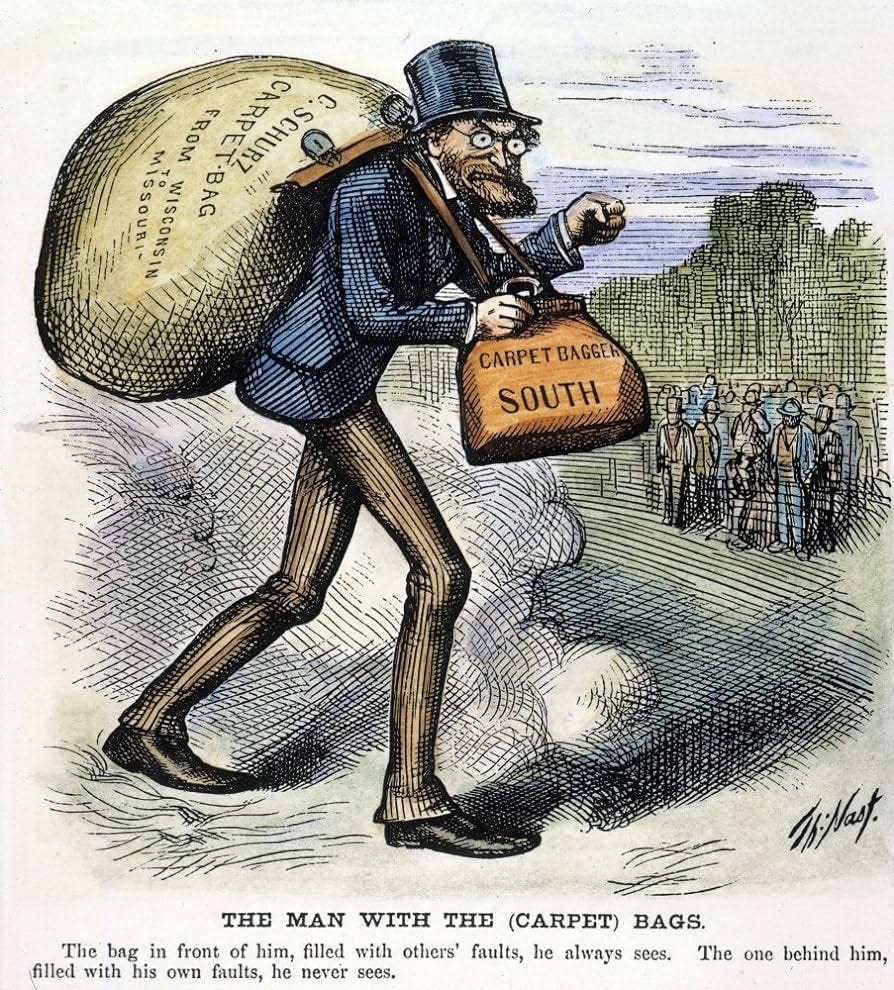

In general, the term “carpetbagger” refers to a traveler who arrives in a new region with only a satchel (or carpetbag) of possessions, and who attempts to profit from or gain control over his new surroundings, often against the will or consent of the original inhabitants.

After 1865, a number of northerners moved to the South “to purchase land, lease plantations or partner with down-and-out planters in the hopes of making money from cotton.”

At first they were welcomed, as southerners saw the need for northern capital and investment to get the devastated region back on its feet. They later became an object of much scorn, as many southerners saw them as “low-class and opportunistic newcomers seeking to get rich on their misfortune.”

In reality, most Reconstruction-era carpetbaggers were “well-educated members of the middle class; they worked as teachers, merchants, journalists or other types of businessmen, or at the Freedman’s Bureau, an organization created by Congress to provide aid for newly liberated Black Americans. Many were former Union soldiers.”

In addition to economic motives, a good number of carpetbaggers saw themselves as reformers and wanted to “shape the postwar South in the image of the North, which they considered to be a more advanced society.”

Though some carpetbaggers undoubtedly lived up to their reputation as corrupt opportunists, many were motivated by a genuine desire for reform and concern for the civil and political rights of freed Blacks.

I stumbled upon a fascinating article entitled “A Carpetbagger in South Carolina” which gives the account of author Louis F. Post’s experience moving to South Carolina after the war. Here is a powerful quote from Post at the end of his article:

“Yet I must renew my expressions of confidence that all this contempt for “carpetbaggers,” “niggers,” “scallawags” and “nigger teachers” was not South Carolina nature but human nature. Put yourself into the South Carolinian’s place and think it over. Certain determining facts must never be let go in considering South Carolina in those times. Her white natives felt themselves a conquered people under the military heel of the conqueror. They beheld a service race arbitrability lifted out of slavery and into political power by a triumphant and blindly ungenerous fore. They saw in immigrants from the conquerors’ distant seat of power only a camp-follower class of low lineage and sordid ambitions. Whether this feeling was just or not makes no difference some extent it was just, though not wholly so. But it was excusable. A sense of outraged loyalty to country or class cares little for such “abstractions” as simple justice. Even the loft well springs of generosity dry up when race liens and class lines are drawn.”

More about Scalawags…

White southern Republicans, known to their enemies as “scalawags,” made up the biggest group of delegates to the Radical Reconstruction-era legislatures. Some scalawags were established planters (mostly in the Deep South) who thought that whites should recognize Blacks’ civil and political rights while still retaining control of political and economic life. Many were former Whigs (conservatives) who saw the Republicans as the successors to their old party.

From History.com:

“The majority of the scalawags were non-slaveholding small farmers as well as merchants, artisans and other professionals who had remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War. Many lived in the northern states of the region, and a number had either served in the Union Army or been imprisoned for Union sympathies. Though they differed in their views on race—many had strong anti-Black attitudes—these men wanted to keep the hated “rebels” from regaining power in the postwar South; they also sought to develop the region’s economy and ensure the survival of its debt-ridden small farms.”

The term scalawag was originally used as far back as the 1840s to describe “a farm animal of little value” and it later came to refer to a worthless person. For opponents of Reconstruction, scalawags “were even lower on the scale of humanity than carpetbaggers, as they were viewed as traitors to the South.”

Scalawags had diverse backgrounds and motives, but all of them shared the belief that they could achieve greater advancement in a Republican South than they could by opposing Reconstruction. Taken together, “scalawags made up roughly 20% percent of the white electorate and wielded a considerable influence.” Many also had political experience from before the war, either as members of Congress or as judges or local officials.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“I did not go to South Carolina as a “carpetbagger.” I did not intend to be one. My expectations were to become a South Carolinian, precisely as I should have expected to become a Californian, an Oregonian, or an Ohioan had my migration been to any of those parts of our common country. But when I realized the circumstances, I meekly accepted the term of reproach and retraced my steps to New York, the state of my first adoption, when I could feel that I was one of the household, even if I had not been born in the house.”

— From “A Carpetbagger in South Carolina” article by Louis F. Post (1925)

Camden, SC article sources:

“Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden.” Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Pratt-1st-Earl-Camden. Accessed 11 May 2024.

Ellison, Virginia. “April, 1791: George Washington Begins His Tour of South Carolina.” South Carolina Historical Society, 16 Apr. 2021, https://schistory.org/april-1791-george-washington-begins-his-tour-of-south-carolina/. Accessed 11 May 2024.

Inabinet, Joan A. “Camden.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, 5 April 2016, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/camden/#:~:text=The%20prosperous%20town%20entertained%20George,Railroad%20reached%20Camden%20in%201848. Accessed 11 May 2024.

“Kershaw-Cornwallis House - SC Picture Project.” SC Picture Project, 13 Nov. 2013, https://www.scpictureproject.org/kershaw-county/kershaw-cornwallis-house.html. Accessed 11 May 2024.

“Lafayette’s Tour.” William G. Pomeroy Foundation, 29 Oct. 2021, https://www.wgpfoundation.org/historic-markers/lafayettes-tour-46/. Accessed 11 May 2024.

Carpetbaggers and Scalawags article sources:

“Carpetbaggers & Scalawags.” HISTORY, https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/carpetbaggers-and-scalawags. Accessed 11 May 2024.

Post, Louis F. “Carpetbagger in South Carolina.” https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.2307/2713666. Accessed 11 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!