#93: The Firing on Fort Sumter, James Byrnes, and Biking Through History

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #93 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

amastergardener

jon@boyettproperties

jenburck

shaft.schroeder

tkukulich

dg_jernigan

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, June 1st at 9:00 am | “Bike Through History” | Starts at Vestibule Coffee and Tea | Clinton, SC | FREE

“Join the Laurens County Trail Association and Prisma Health for an enlightening bike ride to Hammond's Old Store Battle Site. Delve into the stories of courage and strategy at this crucial Revolutionary War landmark. Explore the grounds where pivotal moments in history were made!”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

The Firing on Fort Sumter

The attack on Fort Sumter marked the official beginning of the American Civil War—a war that lasted 4 years, cost the lives of more than 620,000 Americans, and freed 3.9 million enslaved people from bondage.

The election of Abraham Lincoln as president of the United States in 1860—a man who declared “I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free”—threatened the culture and economy of southern slave states and served as a catalyst for secession.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the United States, and by February 2, 1861, six more states followed suit.

Southern delegates met on February 4, 1861, in Montgomery, AL., and established the Confederate States of America, with Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis elected as its provisional president.

Confederate militia forces began seizing United States forts and property throughout the south. With a “lame-duck president in office, and a controversial president-elect poised to succeed him, the crisis approached a boiling point and exploded at Fort Sumter.”

In Charleston, the birthplace of secession, tempers were on edge. A delegation from the state traveled to Washington, D.C., demanding the surrender of the Federal military installations in the new “independent republic of South Carolina.” President James Buchanan refused to comply.

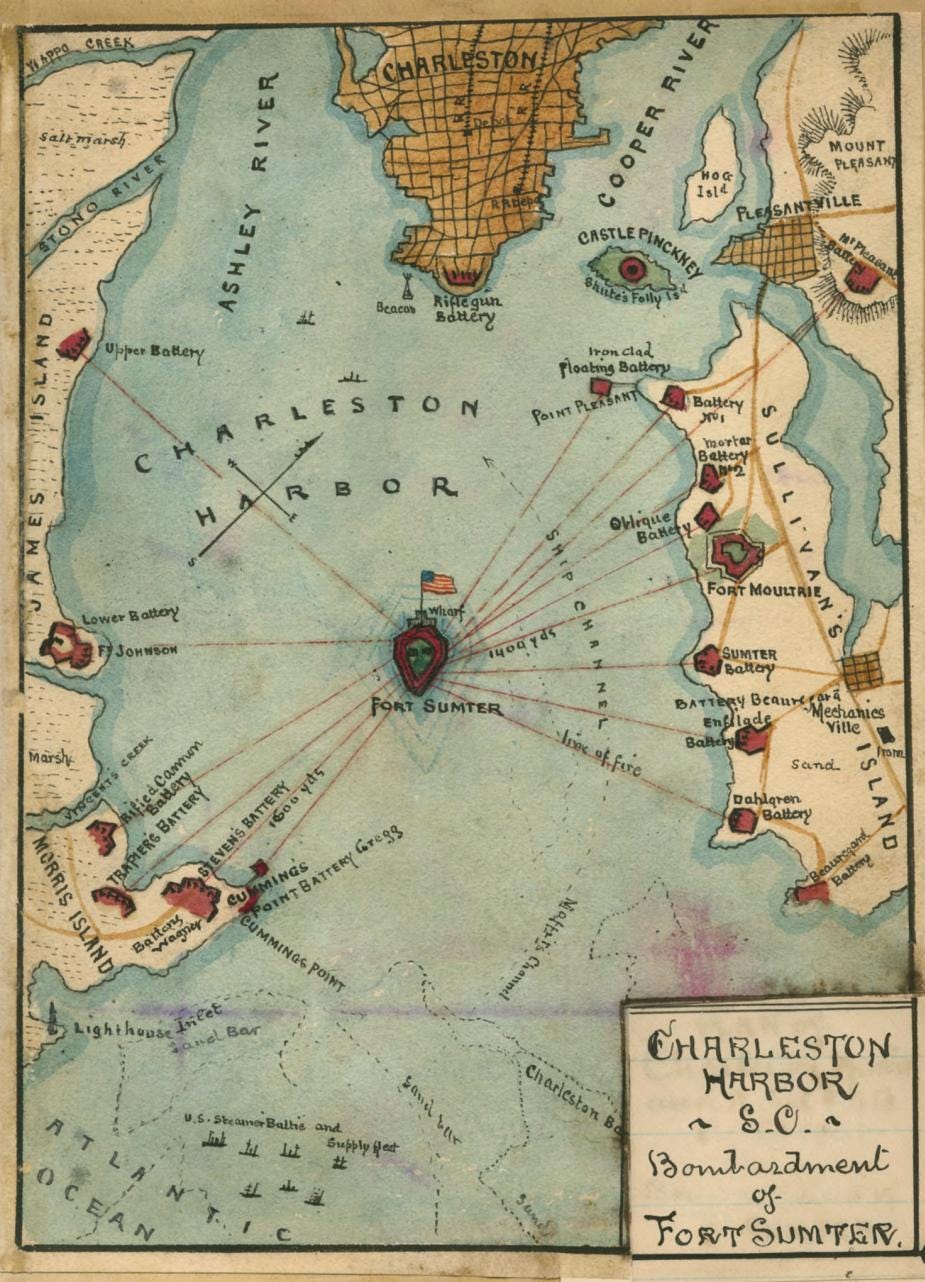

Charleston was the Confederacy’s most important port on the Southeast coast. The harbor was defended by three federal forts: Sumter; Castle Pinckney, one mile off the city’s Battery; and heavily armed Fort Moultrie, on Sullivan’s Island.

Major Robert Anderson’s command was based at Fort Moultrie, but with its guns pointed out to sea, it couldn’t defend a land attack. On December 26, Charlestonians awoke to discover that Anderson and his tiny garrison of 90 Union men slipped away from Fort Moultrie to the more defensible Fort Sumter. For secessionists, Anderson’s move is, as one Charlestonian wrote to a friend, “like casting a spark into a magazine.”

Adding to the Anderson’s concern was his dangerously dwindling store of supplies. On January 5, 1861, the ship Star of the West departed from New York with some 200 reinforcements and provisions for the Sumter garrison.

As the ship approached Charleston Harbor on January 9, cadets from the Citadel fired, forcing the crew to abandon its mission.

On March 1, Jefferson Davis ordered Brig. Gen P.G.T. Beauregard to take command of the growing southern forces in Charleston.

On April 4, Lincoln informed southern delegates that he intended to attempt to resupply Fort Sumter, as its garrison is now critically in need.

To South Carolinians, any attempt to reinforce Sumter meant war.

“Now the issue of battle is to be forced upon us,” declared the Charleston Mercury. “We will meet the invader, and the God of Battles must decide the issue between the hostile hirelings of Abolition hate and Northern tyranny.”

On April 9, Davis and the Confederate cabinet decided to “strike a blow!”

Davis ordered Beauregard to take Fort Sumter. The next day, three of Beauregard’s aides sail to the fort and courteously demanded the garrison’s surrender. Anderson is equally courteous, but refused: “I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication demanding the evacuation of this fort, and to say, in reply thereto, that it is a demand with which I regret that my sense of honor, and of my obligations to my Government, prevent my compliance.” He also informed the delegation that the garrison’s supplies would only last until April 15.

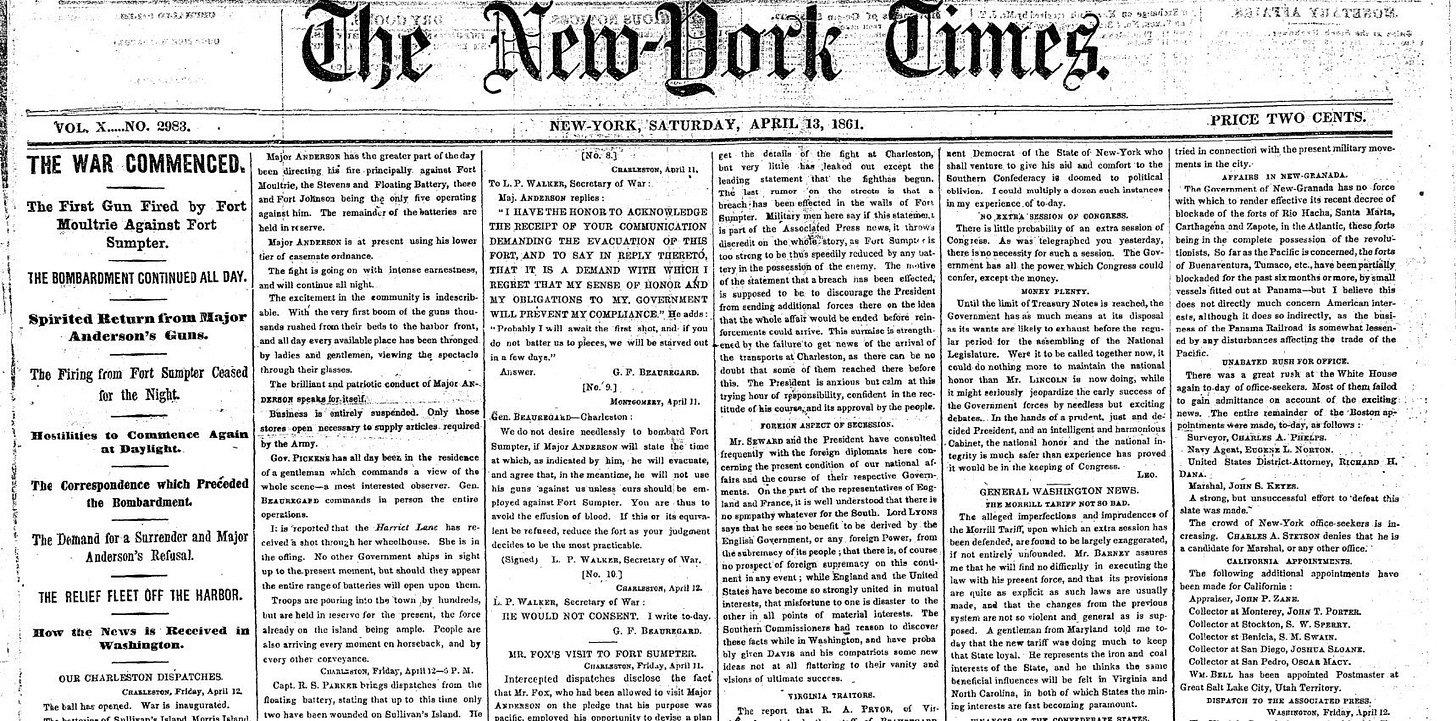

April 12 at 4:30 a.m., a flaming mortar sot soared into the air and exploded over Fort Sumter. On this signal, Confederate guns from fortifications and floating batteries around Charleston Harbor roared to life. Outmanned, outgunned, undersupplied, and nearly surrounded by enemy batteries, Anderson waited until around 7:00 a.m. to respond.

Captain Abner Doubleday volunteered to fire the first cannon at the Confederates, a 32-pound shot that bounced off the roof of the Iron Battery on Cummings Point.

For nearly 36 hours the two sides keep up this unequal contest.

A shell struck the flagpole of Fort Sumter, and the American flag fall to the ground, only to be hoisted back up the hastily repaired pole. Confederates fired hotshot from Fort Moultrie into Fort Sumter. Buildings began to burn within the fort.

With no more resources, Anderson surrendered Fort Sumter to Confederate forces.

April 13 at 2:30 p.m., Major Anderson and his men struck their colors and prepared to leave the fort. Sadly, the only casualties at Fort Sumter came during the 100-gun salute, when a round exploded prematurely, killing Pvt. Daniel Hough and mortally wounding another soldier.

The attack was over, but the war had just begun.

Following the evacuation of Major Robert Anderson and his Federal garrison on the afternoon of April 14, 1861, Fort Sumter was occupied initially by Confederate troops of Company B of the First South Carolina Artillery Battalion and a volunteer company of the Palmetto Guard, a local militia unit.

The fort remained in Confederate hands for the next four years until all Confederate forces evacuated Charleston on the evening of February 17, 1865.

Despite having surrendered, Anderson and his men were greeted as heroes when they disembarked in New York. Capt. Abner Doubleday noted later that “all the passing steamers saluted us with their steam-whistles and bells, and cheer after cheer went up from the ferry boats and vessels in the harbor.”

Anderson’s valor during the attack and commitment to duty were praised by the Union.

Beauregard was also hailed for this first Confederate victory. He was later ordered to direct the troops at Bull Run.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

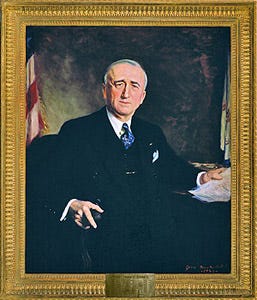

Did you know that Charlestonian James Byrnes is one of the few people in history to have served in the Legislative, Judicial, and Executive branches of the federal government?

(Note from Kate: Thank you to subscriber Jeffrey K. Smith for encouraging me to research and write about James Brynes!)

During his distinguished political career, James Byrnes served as a Congressman, U.S. Senator, U.S. Supreme Court Justice, U.S. Secretary of State, and Governor. He is one of the few people in history to have served in the Legislative, Judicial, and Executive branches of the federal government. Here is a list of others who achieved this political milestone.

Over his lifetime Byrnes held many public positions, “coming closer than any other South Carolinian in the twentieth century to obtaining the national political influence wielded by John C. Calhoun in the nineteenth century.”

Byrnes was born in Charleston on May 2, 1882, the son of James Francis Byrnes, an Irish Catholic city clerk, and his Irish Catholic wife, Elizabeth McSweeney.

Seven weeks before his birth, Byrnes’s father died of tuberculosis, leaving “Jimmy” to be reared by his widowed mother.

In his early teens Byrnes left school to work in a Charleston law office to help support the family.

His public career began in 1900 when Judge James Aldrich of Aiken appointed Byrnes court stenographer for the six-county Second Judicial Circuit. When not traveling to circuit court sessions between Aiken and Beaufort, Byrnes studied law in Judge Aldrich’s office, and by 1904 he was licensed to practice law.

In 1908 Byrnes was elected circuit court solicitor. At that time solicitors spent part of the year in Columbia assisting legislators in bill drafting.

Building on political connections from the circuit court and the legislature, he was elected U.S. congressman and served for fourteen years (1911–1925).

Byrnes helped establish the first national highway system, including U.S. Highway 1 through his hometown of Aiken, based on payments to states for roads used by mail carriers or in interstate commerce.

Byrnes worked on House appropriations, especially financing military operations during World War I, and came to know Franklin D. Roosevelt. Byrnes was also instrumental in passage of the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, which consolidated the power of the House Appropriations Committee and created a director of the budget.

In 1924 Byrnes was defeated in a bid for the U.S. Senate by Cole L. Blease.

However, Byrnes unseated Blease in 1930 and was elected U.S. senator in 1936.

Byrnes had maintained his earlier association with Roosevelt, advising him to run for governor of New York in 1924 and supporting his run for the presidency in 1932.

As a senator, Byrnes became “an influential advocate of President Roosevelt’s New Deal programs,” helping to write many of the emergency economic laws in “the first 100 days” of Roosevelt’s administration.

In 1941 Byrnes resigned from the Senate when Roosevelt appointed him associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Sixteen months after joining the Supreme Court, in October 1942, Byrnes resigned so that President Roosevelt could appoint him director of the Office of Economic Stabilization, which coordinated federal efforts to control the inflationary effects of increased war spending.

In May 1943 Byrnes became director of war mobilization, a position with enough powers to earn him the nickname “Assistant President.”

Like Bernard Baruch (also a South Carolinian), who had served President Woodrow Wilson in a similar capacity during World War I, Byrnes was “responsible for unifying the nation’s industrial production programs for World War II.”

With such a distinguished record, Byrnes was widely rumored to be Roosevelt’s nominee for vice president in 1944. His chances failed after he was “opposed by Catholic political leaders who characterized him as a deserter to his native church, by northern minorities who feared him as a segregationist, and by organized labor who opposed his anti-labor-union, right-to-work views.”

After Roosevelt’s death, Byrnes served as U.S. Secretary of State under President Harry Truman from July 3, 1945, until January 20, 1947. His activities were central in defining postwar U.S. foreign policy.

Along with President Truman, he was one of 4 representatives at the Potsdam Conference near Berlin in July 1945, and he confronted ongoing issues among the Allies and the Soviets.

In 1945, Byrnes was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal by President Truman for his work in the Office of War Mobilization.

As head of the wartime Office of War Mobilization, Byrnes provided oversight, material and financial resources for the high priority Manhattan Project, which produced the first nuclear weapons.

In the 2023 blockbuster film Oppenheimer (which portrayed the evolution of the Manhattan Project), directed by Christopher Nolan, Byrnes was portrayed by actor Pat Skipper.

In the years that followed, Byrnes subsequently feuded with Truman over the politics of foreign policy, particularly related to Russia.

Truman and others believed that Byrnes had “grown resentful that he had not been Roosevelt's running mate and successor and so was showing disrespect to Truman.” Whether or not that was true, Byrnes felt compelled to resign from the Cabinet in 1947 with some feelings of bitterness.

He was not done with public service yet, however. At the age of 68, Byrnes was elected Governor of South Carolina in 1950. He stated in his inaugural address:

“Whatever is necessary to continue the separation of the races in the schools of South Carolina is going to be done by the white people of the state. That is my ticket as a private citizen. It will be my ticket as governor.”

He proposed some reforms, including more funds for the state hospital for the mentally ill. Central, however, was his position on racial segregation and public education.

As an advocate of the “separate but equal” policy, Byrnes remained a segregationist. Critics saw his stance as a lost opportunity for perhaps the only political leader in the region with sufficient national stature, a “modern day Calhoun,” to exercise the leadership to end racial segregation. Instead, Byrnes blamed “Negro agitators” and “Washington politicians” and even threatened to abandon the public school system rather than desegregate.

His politics became more and more distant from the national Democratic Party.

In 1952 he endorsed Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Republican presidential candidate, and invited “Ike” to speak from the State House steps in Columbia. Byrnes supported Eisenhower in 1956 and Richard M. Nixon in the 1960 presidential election.

Byrnes retired from active political life after the 1954 gubernatorial election.

Byrnes wrote two autobiographies, Speaking Frankly (1947) and All in One Lifetime (1958). The royalties were donated to the Byrnes Foundation, which granted college scholarships to South Carolina orphans.

Byrnes died in his Columbia home on April 9, 1972. He was buried in the Trinity Episcopal Church cemetery.

Byrnes is memorialized at several South Carolina universities and schools:

The James F. Byrnes Building, housing the Byrnes International Center at the University of South Carolina.

The James F. Byrnes Professorship of International Studies at USC, its first endowed professorship.

Byrnes Auditorium at Winthrop University.

Byrnes Hall, a dormitory at Clemson University, where Byrnes was a Life Trustee.

James F. Byrnes High School in Duncan, South Carolina.

Byrnes' portrait hangs in the South Carolina Senate chambers.

From South Carolina Encyclopedia:

“Byrnes left a series of political legacies in South Carolina, the nation, and the world. His advocacy of highway and New Deal legislation provided numerous material benefits to South Carolinians. His services to President Roosevelt had a major impact on the national economy during World War II. His role as secretary of state was instrumental in defining postwar foreign policy. In the 1950s and 1960s Byrnes’s support of Republican presidential candidates was a key factor in the party’s revitalization in the South.”

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“I look back over the men that I have known around the world and in this country, and I have known great Congressmen, Senators, Governors, Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, Secretaries of State, and men who have served in wartime as the top advisers to the President of the United States. But never in American history has one man held more high offices with more distinction than Governor Byrnes of South Carolina.”

— President Richard Nixon Remarks in Columbia, S.C., During a Visit With Former Governor and Mrs. James Byrnes (1969)

Fort Sumter article sources:

“Fort Sumter Battle Facts and Summary | American Battlefield Trust.” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/fort-sumter. Accessed 11 May 2024.

James Byrnes article sources:

Blease, Cole. “Byrnes, James Francis.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, 17 May 2016, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/byrnes-james-francis/. Accessed 11 May 2024.

“President Harry S. Truman Presenting the Distinguished Service Medal to James F. Byrnes.” Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/99-164. Accessed 11 May 2024.

“Richard Nixon Remarks in Columbia, S.C., During a Visit With Former Governor and Mrs. James Byrnes.” The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-columbia-sc-during-visit-with-former-governor-and-mrs-james-byrnes. Accessed 11 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!