#35: The Father of Modern Greenville, a vintage Krispy Kreme, and a lecture on Eliza Pinckney and her sons

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #35 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

Welcome “tmoore028” “syldrown” “jenmcdole70” “karen.herbert1822” and “jlmbloodwo67” to our SC History Newsletter community! Woohoo!

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Tuesday, March 19th at 7:00 pm | “Daniel Island Historical Society Presents: Raising Revolutionaries: Eliza Pinckney and Her Sons” | Church of the Holy Spirit Parish Hall | Daniel Island, SC | FREE

“Join the Daniel Island Historical Society as we spotlight Eliza Lucas Pinckney and two of her children for Women’s History Month in March! In some ways, Eliza Lucas Pinckney has come to overshadow her sons. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney was a signer of the Constitution and Thomas Pinckney was Governor of South Carolina and the first U.S. Minister to the Court of St. James. Our guest speaker Faye Jensen, CEO Emerita of the South Carolina Historical Society, will draw from the Society’s collection of Pinckney Family papers to focus on Eliza’s parenting style and her relationship with her sons.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Did you know that the mayor responsible for the revitalization of Greenville, SC was a Jew who had fled Nazi Germany with his family?

Today, Greenville is heralded as one of the “top best places to live,” “top 4 best small cities in the US,” “top 10 US cities for beauty, affordability, and food,” among many other impressive headlines. But before Greenville was the beautiful “city on the rise” it is today, downtown Greenville went through a serious decline that left many buildings abandoned and the streets unsafe. A very unlikely man would come to be the “Father of Modern Greenville” and help the city rise again.

Max Moses Heller (1919 – 2011) was born on May 28, 1919, in Vienna, Austria to his parents Israel and Leah Heller. Israel Heller, a native of Poland and a veteran of World War I, operated a sales business with his wife. After graduating from high school, Max Heller was “apprenticed to a novelty store owner, rising to the position of buyer, and attended business school part time.”

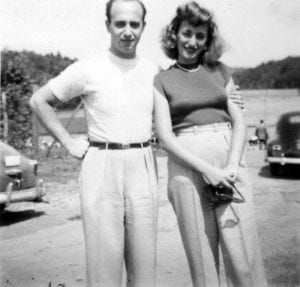

When Max was 17, he went to a summer resort outside of Vienna, where he met a young lady named Trude Schonthal (age 14). The day they met Max “declared his love and said he would marry her someday.” According to Trude, “He always kept his word.” Later that week, for “a reason Max could never understand,” he decided to return to Vienna for a night to go dancing. He met up with a friend and they spotted a table of American girls who were on a graduation trip to Europe. One of those girls was Greenville native Mary Mills. The two exchanged addresses and communicated used Max’s English/German dictionary. Little did they know that Mary would soon become Max’s “angel.”

On March 11, 1938, Austria was invaded by the Nazis. Hellers’ parents lost their business, and Max lost his job at the novelty store. Seeing the situation as dire, Max convinced his parents that their the family must leave Europe. Max took a chance and wrote to his American friend Mary Mills in Greenville — asking for help. Mary brought Max’s letter to Shepard Saltzman, owner of Piedmont Shirt Company in Greenville, and asked him to sponsor Max’s immigration to the United States. Saltzman replied, “How can I, a Jew, refuse, when you, a Christian, is asking?”

Max Heller received a letter back from Mary Mills saying that she had worked with Saltzman to arrange for the Hellers’ safe passage to the United States. In the video I share further below, Max says, “I cannot describe to you the feeling of getting this letter. My life was in her hands.” Max arrived in Greenville a few months later and began working at Saltzman’s shirt factory the very same day. He says, “It was like heaven…freedom… here in Greenville.” For the rest of his life Max would call Mary Mills his “angel.” Max’s sister Paula and their parents would arrive in Greenville shortly thereafter.

Trude Schonthal, Max’s fiancée, left Vienna in 1939 and eventually came to Greenville with her mother by way of Belgium. Her father escaped from a concentration camp in France and joined the family. Max and Trude Heller married in 1942 and had three children.

Max started at Piedmont Shirt Company as a stock clerk — sweeping floors at $10 a week — and eventually became vice president and general manager. In 1946, he established the Williamston Shirt Company, which he sold in 1948. He subsequently formed the Maxton Shirt Company, which he sold in 1962 but continued to work for until 1967.

Meanwhile, Max also became active in community affairs in Greenville. He was a member of Congregation Beth Israel, and served as president of the congregation. He became concerned about “youthful offenders and urban housing for the poor.”

From the late 19th century through the mid-20th, Greenville had been a thriving city due to its powerful textile industry, even earning it the moniker “The Textile Capital of the World.” After WWII, downtown Greenville was buzzing with life with “four national highways” siphoning into it, shops, restaurants, and more. However, by the 1960s, the textile industry faced increased foreign competition, and mills began to go out of business. As the core industry of the city declined, so did downtown Greenville.

One Greenville native remembers:

The downtown I remember as a child in the 1960s was much different. Main Street was a four-lane urban thoroughfare, lined with department stores. We used to go to “Bob’s Men’s Shop” whenever our parents decided we needed some new dress-up clothes. Bob McGinnis’ music store, just off Main Street, was where we stocked up on supplies for my mom’s guitar students. To look at old photos of downtown Greenville, you’d almost think you were looking at some big metropolis, like Chicago, with the impressive number of cars on the roads and people on the streets, the vast tangle of power lines and streetcar rails.

I moved away for a few years during the 1970s when downtown fell into decline. Retail moved to the suburbs and the drug dealers and prostitutes moved in.

Indeed, many other Greenvillians speak of the 1970s when downtown Greenville was “not a place you wanted to be” with abandoned stores, broken windows, drug dealers squatting in abandoned buildings, and prostitutes roaming the streets. This was the Greenville Max Heller knew he had to save.

Max joined the Greenville City Council in 1968 and became mayor from 1971 to 1979. During his time as mayor he worked with Greenville business and civil leaders like Buck Mickel and Tommy Wyche to revitalize downtown. Together, they negotiated federal support for a convention center as part of the Hyatt hotel downtown, and urged the beautification and narrowing of Main Street. Influenced by his European roots, Max envisioned a more intimate, walkable downtown Greenville. He hired one of the best urban planners in the United States at the time, Lawrence Halprin to conceive of downtown’s new look. They narrowed Main Street from 4 lanes to 2 lanes, and widened the sidewalks to allow for sidewalk cafes. They planted young trees, and added diagonal parking, planters, and decorative crosswalks. All this laid the foundational groundwork for the downtown Greenville we know and love today.

In city planning reports as early as 1907, there was also a great desire to revitalize and highlight the Reedy River and and the large waterfall in the center of Greenville, but during Max’s tenure as mayor, the falls were covered by a highway. It would later be the project of Mayor Knox White (currently serving his final term in office) to expose the falls and make it a wonderful destination at the heart of the city. (Note from Kate: the transformation of Greenville’s Falls Park will certainly be a subject for a future newsletter)

As Max Heller worked to revitalize Greenville, he was the first mayor to have 4 year terms. He “championed the desegregation of city hall” and membership of municipal commissions, and the building of community centers. To provide more economical public transportation, he also led the creation of the Greenville Transit Authority.

In 1979, Governor Richard Riley appointed Max the chairman of the State Development Board. In 5 years Max “oversaw the creation of 67,000 jobs and the South Carolina Research Authority, and the recruitment of diversified companies such as Michelin North America, Union Camp, and Digital Computer. Under his leadership the annual recruitment of industry hit the $1 billion mark.”

Here is a video ETV of Max Heller’s story:

For their contributions to the city of Greenville, Max and Trude Heller received the Order of the Jewish Palmetto from the Jewish Historical Society in April 2007. In downtown Greenville, there is a plaza named after Max Heller and a statue in his honor proudly looking over Main Street. He died on June 13, 2011, at the age of 92 in Greenville.

II.

Did you know that the Krispy Kreme location on N. Church Street in Spartanburg is one of the only 11 remaining vintage Krispy Kreme coffee bars in the country?

In 1933, a man named Vernon Rudolph met Joe LeBeau, a French chef in New Orleans, and purchased “a secret yeast-raised doughnut recipe and the copyrighted name Krispy Kreme.” Rudolph and his uncle began selling these special new doughnuts door-to-door out of the back of their car, “a 1936 Pontiac with a delivery rack in the backseat.” As demand for his fresh doughnuts grew, Rudolph converted his doughnut-making facility in the Old Salem area of North Carolina into a retail store by “cutting a hole in the wall and installing a sales window.” On July 13, 1937, Krispy Kreme Doughnuts opened.

As demand grew, Krispy Kreme expanded and opened new stores across the Carolinas. By the 1960s, Krispy Kreme stores were visible throughout the Southeast with recognizable, green-tiled roofs, heritage road signs, and glowing neon signs announcing “Hot Doughnuts Now.” These signature features helped brand the Krispy Kreme chain as stores opened outside the region.

W. W. Reese opened this iconic, now abandoned, Krispy Kreme on North Church Street in Spartanburg in October 1969. The family-owned business was later passed down to his son, Glenn. This location featured a coffee bar and is one of the only 11 Krispy Kreme coffee bars still remaining in the country. Patrons sat at the counter and paid 50 cents for coffee. While other Krispy Kreme’s served coffee in Styrofoam cups, the Spartanburg location was the last to use real China chips. In its hey day, the store made and sold more than “36,000 doughnuts a day in order to overcome $4,000 worth of daily overhead.”

Glenn started his career as a school teacher and eventually went into politics, while continuing to own the Krispy Kreme. In 1990, at the age of 48, Glenn ran for state senate in District 11 and won. In 2020, after 30 years in the S.C. Senate, Senator Reese lost his re-election bid and decided to retire from politics. His Krispy Kreme store was “a magnet for Democratic presidential candidates including Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden.” In 2022, Reese listed the old Krispy Kreme for sale for $785,000, and there is now a new Krispy Kreme across the street located at 354 N. Church Street. I was unable to find any information on the (old) store’s new ownership. While the new location is very nice, I think I can safely say that us history lovers would love to see the old location brought back to its former, vintage glory and operational again!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

I.

“My father credited Greenville with giving him a new life. In return, working with other forward-thinking people, he gave Greenville new life. Between 1971 and ’79, during his tenure as mayor, his first hire was an African-American woman—the first in City Hall. He saw to it that affordable housing was built; diversity in municipal departments was achieved; community centers and senior housing were established; pensions for policemen and firemen were assured. He brought with him a European vision of downtown—pedestrian friendly and green—that could be enjoyed by citizens and visitors to the city. He was instrumental in bringing numerous businesses, such as Michelin, to the Greenville area. Max is often referred to as the “Father of Modern Greenville.”

— Susan Heller Moses, daughter of Max Heller

Sources used in today’s newsletter:

Downtown Greenville: From birth to bustle, decline to revitalization

Max and Trude Heller Receive The Order of the Jewish Palmetto

Coffee, doughnuts and the year 2000 Spartanburg Krispy Kreme one of last of the originals

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!

When I lived in Greenville from 1997 to 2000, it was on the cusp of what it has since become - a thriving, New South Mecca. Pigeons still flew in and out of the broken windows of the abandoned Poinsett Hotel back then, and cars still drove along Camperdown Bridge, the Reedy River hidden below. But you could sense possibility along the sidewalks of Main like a wound coil, becoming less Bob Jones and more Max Heller by the day. Cheers to Max, and cheers to Greenville.