#97: South-Carolina Gazette, John Lining, and Drayton Hall at Night

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 21st, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #97 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

SamCrews3

akmwaters

tylerhembree

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, June 15th evening | “Drayton Hall at Night” | Drayton Hall | Charleston, SC | Tickets: $20-$60

“Experience Drayton Hall after hours! Bring a date, a group of friends, or the family to Drayton Hall at Night!

Enjoy the beautiful landscape and live music on the lawn. The house will be open to tour and talk with our knowledgeable interpreters as well as our archaeologists who will be on the landscape to tell you about their most recent finds.

Bring a picnic or pre-purchase a cheese and charcuterie tray.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

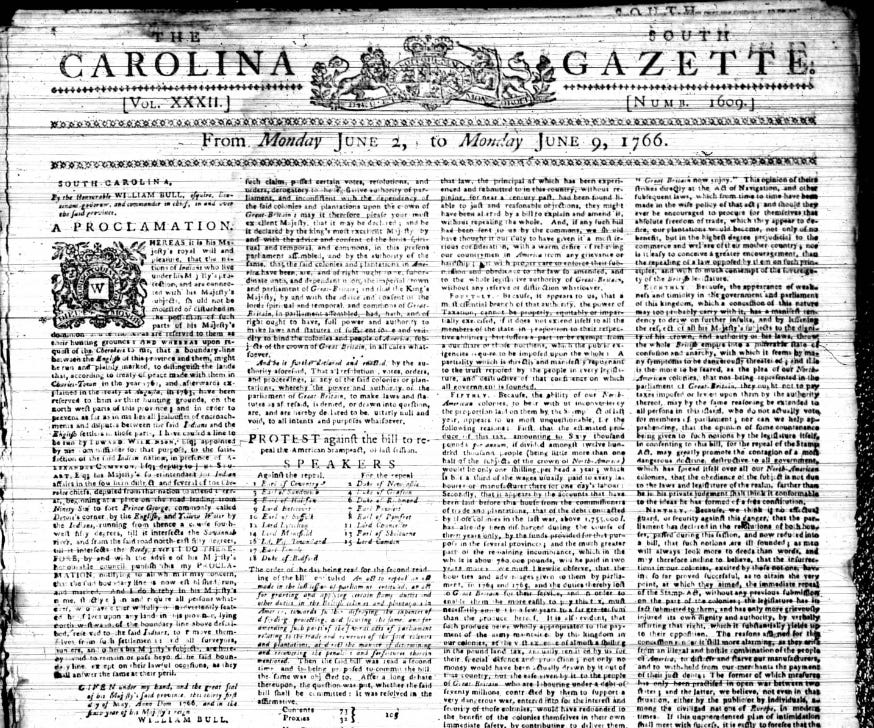

Did you know that the South-Carolina Gazette was SC’s first newspaper, and at one time, was run by the first female printer in the colonies?

In 1731, the General Assembly recognized the need for the publication of a newspaper in the colony and offered “£1,000 to a printer who would move to South Carolina and open for business.”

Printers George Webb, Eleazer Phillips, and Thomas Whitmarsh moved to Charleston to vie for the money. Phillips and Whitmarsh began publishing newspapers soon after they arrived.

No copies of Phillips’s paper, the South-Carolina Weekly Journal, have survived, and publication stopped after his death in July 1732.

Whitmarsh’s paper, the South-Carolina Gazette, began publication on January 8, 1732, and continued with some interruptions for more than 4 decades.

Whitmarsh was a native of England and a former employee of Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia. After Whitmarsh died in September 1733, the paper was published by the Timothy family.

Lewis Timothy was a journeyman printer from France who was also a business partner of Benjamin Franklin. Franklin established “Louis in a 6-year business partnership as the new printer of the South-Carolina Gazette.”

Lewis, his wife Elizabeth, and their children moved to Charleston, and he restarted the newspaper in 1734. His young son Peter was designated as his successor.

By 1736, Lewis Timothy prospered as a landholder and printer, serving as the official colonial printer for South Carolina.

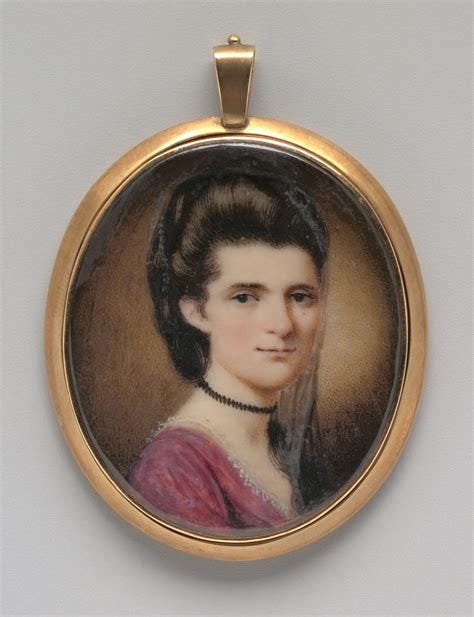

In December 1738, Lewis died as the result of “an unhappy Accident,” leaving Elizabeth in the care of “six small Children and another hourly expected.” She had already mourned the loss of two of her children by 1737.

According to the arrangement between her husband and Franklin, Elizabeth’s eldest son, Peter, was to carry on the business in the event of his father’s death. But because of Peter’s youth, she assumed control of the printing office as well as responsibility for her family.

The newly widowed Elizabeth published the next issue of the Gazette on January 4, 1739, pledging to the readership:

“Whereas the late Printer of this Gazette hath been deprived of his life, by an unhappy accident, I shall take this Opportunity of informing the Publick that I shall continue the said Paper as usual; and hope, by the Alliance of my friends, to make it as entertaining and correct as may be reasonably expected.”

By the end of the year, Elizabeth bought out Benjamin Franklin’s interest in the partnership and became the first woman in the American colonies to own and publish a newspaper.

Franklin “praised her regular and exact accounting” and commended her for “both raising a family and purchasing the printing operation from him.”

Elizabeth gradually relinquished control of printing operations when her son Peter came of age in 1746. Requests for payment from the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly from 1740 to 1743 in Elizabeth’s name show her reliance on the revenues as public printer.

In addition to publishing the Gazette and colonial laws, “she sold legal blanks, broadsides, and stationery and established a bookstore adjacent to her son’s printing office.”

By 1764 the Gazette had subscription agents in North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

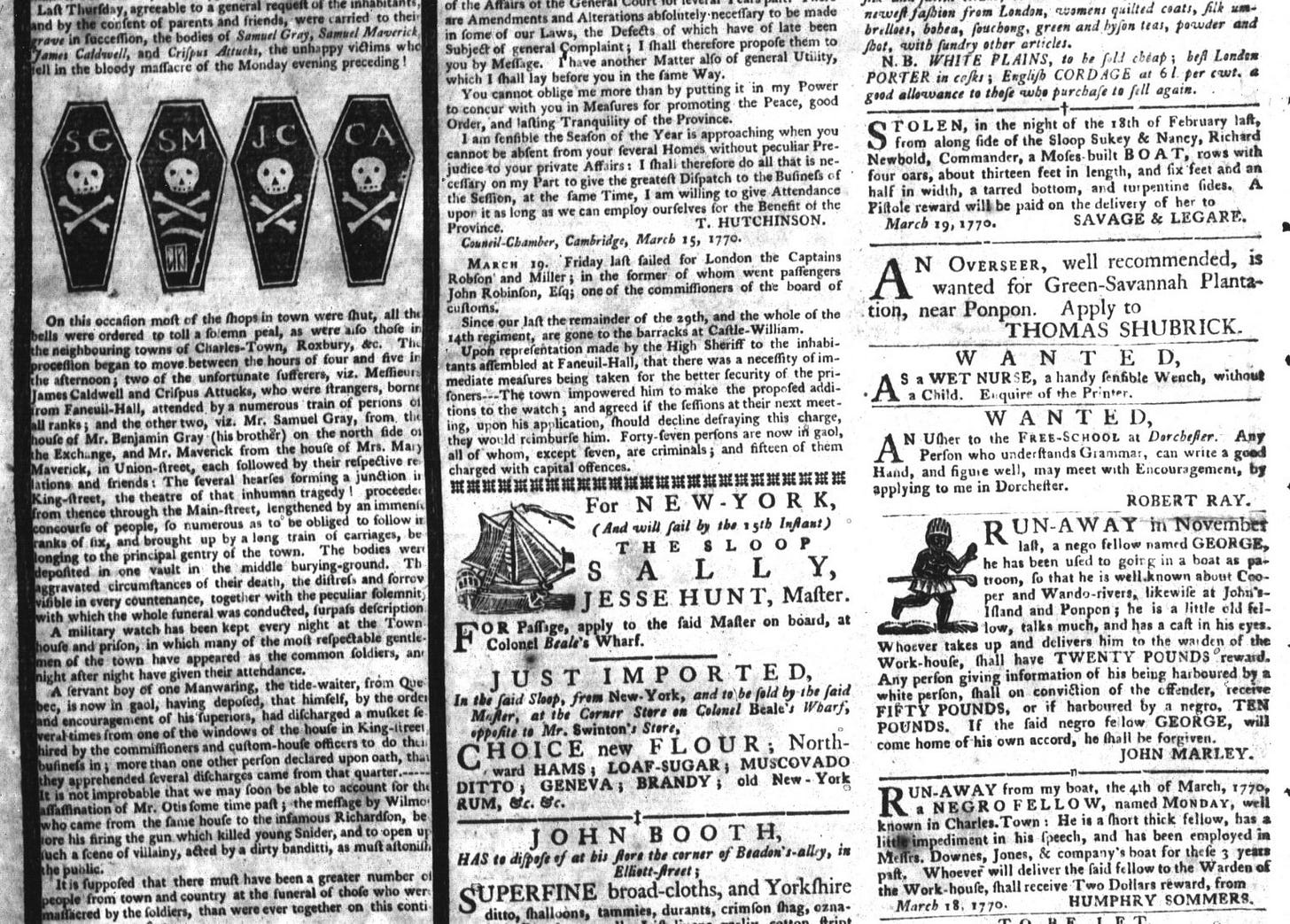

The newspaper had “a typical mix of news items, advertisements, reprinted material from other periodicals, and literature.”

Small woodcuts were published from 1735 onward.

Although the newspaper was generally apolitical, Peter Timothy eventually “became a vocal supporter of the Revolutionary cause.”

The Boston Massacre and blockade of Boston were both announced in the newspaper with heavy black borders. The newspaper printed the names of those who violated nonimportation, and Timothy “remained in close contact with Benjamin Franklin and the Boston patriot leader Samuel Adams.”

The Gazette continued to be a strong supporter of the rebel cause until it ceased publication in December 1775.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you know that John Lining was a prominent doctor and scientist in early Charleston?

Lining was born in April 1708 in Lanarkshire, Scotland, the son of Thomas Lining, a minister, and Anne Hamilton.

He studied medicine in Scotland and probably at Leyden University in the Netherlands as well.

He immigrated to Charleston in 1728, and by the early 1730s he was advertising “the sale of medicinal waters and drugs in the South-Carolina Gazette.”

He served as physician to the poor of St. Philip’s Parish and as port physician for the enforcement of quarantine.

He built a successful medical practice and entered into partnership with Lionel Chalmers around 1740.

In 1750 he married Sarah Hill, an heiress with several valuable parcels of property. They had no children.

He abandoned the practice of medicine in 1754 after he was attacked by “gout” and turned to “raising indigo and experimenting with electricity.”

Lining was a justice of the court of general sessions and the court of common pleas, president of the Charleston Library Society, a founder of the St. Andrews’s Society, and a Mason.

Lining’s scientific pursuits began as early as 1737, when he began making careful meteorological observations “using a barometer, a thermometer, and a hygroscope.”

He continued keeping these records for 15 years and published some of his results in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1748 and 1753.

These observations, which also appeared in Governor James Glen’s Description of South Carolina (1761), are reputed to be “the earliest published meteorological records from America.”

In 1740 Lining started making metabolic, or what he called “statical,” experiments on himself, keeping a “careful record of his intake of food and output of excretions.”

He hoped to establish a connection between the effects of weather conditions on bodily functions and disease, particularly the fevers that struck the colony regularly at specific times of the year. Although unable to demonstrate a connection, he sent his observations to the Royal Society, and they were published in the society’s Transactions in 1742–1743 and 1744–1745. Lionel Chalmers later included them in his Account of the Weather and Diseases of South Carolina (1776).

Lining was also an avid botanist who collected and sent many plant specimens to Charles Alston and Robert Whytt of Edinburgh University.

In a paper published in Edinburgh in 1754, Lining described the benefits and toxicity of the Indian pinkroot as a vermifuge (worm remover or destroyer).

Lining’s most significant work on medicine was “A Description of the American Yellow Fever,” published in Edinburgh in 1756.

This essay is often referred to as the first North American account of yellow fever, but it was preceded by John Moultrie, Jr.’s 1749 Edinburgh dissertation on the disease. Lining presented “a clear, detailed clinical description of the disease’s symptoms, course, and prognosis. He argued that it was contagious and that it was imported from outside, usually from the West Indies. But he also noted the important, if apparently contradictory, fact that country residents infected while in town did not transmit it to their families. He concluded correctly that one attack of yellow fever conferred future immunity, but incorrectly that Africans were naturally immune to it.”

Lining died in Charleston on September 21, 1760.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ SC History Quote

“In obedience to your desire, I have sent you the history of the yellow fever as it appeared here in the year 1748, which, as far as I can remember, agreed in its symptoms with the same disease, when it visited this town in former years. In this history, I have confined myself to the faithful narration of facts and have avoided any physical inquiry into the causes of the several symptoms in this disease; as that would have required more leisure than I am, at present, master of, and would perhaps have been less useful than plain description.”

—First paragraph of John Linings “A Description of the American Yellow Fever” published in Edinburgh in 1756.

South-Carolina Gazette article sources:

King, Martha J. “Timothy, Elizabeth.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, 28 June 2016, University of South Carolina, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/timothy-elizabeth/. Accessed 12 May 2024.

Marrs, Aaron W. “South-Carolina Gazette.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies, 1 August 2016, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/south-carolina-gazette/. Accessed 12 May 2024.

“Patriots & Printers: The Timothy Family of Charleston.” MarkJonesBooks, https://www.facebook.com/WordPresscom, 27 Sept. 2023, https://mark-jones-books.com/2023/09/27/patriots-printers-the-timothy-family-of-charleston/. Accessed 12 May 2024.

John Lining article sources:

“A Description of the American Yellow Fever, Which Prevailed at Charleston, in South Carolina, in the Year 1748 / by Doctor John Lining, Physician at Charleston.” Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/

y8xjbppu/items?canvas=7. Accessed 12 May 2024.McCandless, Peter. “Lining, John.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, 8 June 2016, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/lining-john/. Accessed 12 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!