#148: Mysteries of "The Old Plantation" Painting + Revolutionary Battlefield Treasures

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, upcoming SC historical events, and other South Carolina recommendations.

Dear readers,

I love it when I discover very niche stories in my South Carolina research.

Today’s topic simply started with a Google query of “earliest paintings of South Carolina plantations” and what I discovered were the stories of the fascinating paintings below — what they reveal to us about plantation culture, slave culture, early colonial life, and more.

I hope you enjoy!

Sincerely,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Support the SC History Newsletter by considering heritages teas (inspired by South Carolina and American history!) from our fantastic sponsor Oliver Pluff & Co. — click on their beautiful ad below! :)

➳ Housekeeping for new subscribers!

New friends! There are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and more! See our archive here!

Send me your comments or topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Have additional ideas or feedback? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Keep the conversation going and join over 100 other subscribers by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here!

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

Love the SC History Newsletter? Please click the button below to share with a friend!

➳ Featured Upcoming SC History Events

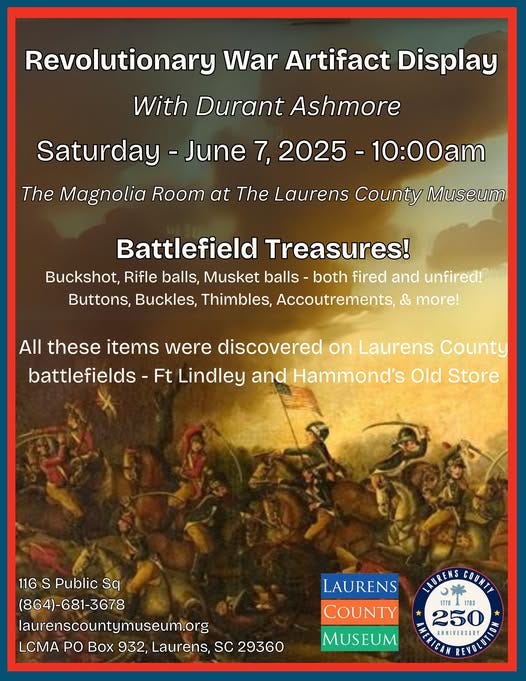

🗓️ Saturday, June 7th at 10:00 am

📝 Revolutionary War Artifact Display: Battlefield Treasures!

📍Laurens County Museum | Laurens, SC

💻 Website

➳ 🗓️ Paid subscribers get access to my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

➳ The Mystery of "The Old Plantation" Painting

Painted as a watercolor sometime between 1785-1790, the painting above, known as “The Old Plantation,” is known by scholars as perhaps one of the earliest and most realistic depictions of enslaved workers on an antebellum plantation.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has said that this painting shows the efforts of the depicted enslaved men and women “to maintain African cultural traditions within the difficult, often hostile context of plantation life.”

“The Old Plantation” painting has long been a mystery to scholars — who painted it? Where is it from? What is its meaning?

Thankfully, we now have some answers, thanks to Colonial Williamsburg decorative arts librarian Susan P. Shames. Through her research, she has attributed this artwork to John Rose, who was a plantation owner in Beaufort, South Carolina in the late 18th century.

Scholars believe the scene above took place on John Rose’s plantation, and that these may have been depictions of his own slaves. It is believed he owned roughly 50 enslaved workers.

What is happening in the scene? The enslaved workers are in a moment of leisure and celebration. At the right, a musician plays a 4-stringed banjo (perhaps from a hollowed gourd), and the other musician seems to be beating on a makeshift drum (perhaps an overturned pot or pan). The man in the middle is dancing. The women to the left are holding scarves. Scholars believe these may have been African percussive instruments known as a “segburehs” which may have had shells or rattles sewn into them. The figures are depicted wearing their “best clothes” in the late 18th century working class style, though John Rose may have “sanitized” their outfits to appear cleaner and likely less tattered than they would have been in real life. Though if the figures above were “house slaves,” they would have had nicer attire than those in the fields. Note the figures’ feet: most South Carolina slaves went barefoot. The three containers on the ground by the musicians: there is a brown job (probable stoneware), a glass bottle (for wine?), and a white salt-glazed stoneware jug. In the background on the river are 2 canoes, which would have been common to see at the time. The two wooden structures behind the figures appear to be slave cabins — with the scene representing a dance in the slave quarters.

Some scholars believe this scene depicts a marriage ceremony, with the tradition of “jumping the broom.” Others believe the subjects are simply performing a secular dance. West African dancing will typically include “sticks and variety of body positions.”

What is the origin of the “jumping the broom” tradition? According to Brides.com:

“The history of jumping the broom is a bit complex, with several conflicting accounts about the origin of the ritual. Some argue that it originated in West Africa, as brooms were used as a way to ward off evil spirits. Specifically, family members or members of the community would wave a broom over the couple's head, and then place it on the ground for the couple to jump over it. It's even said that a good-natured joke was whoever jumped the broom the highest was designated as the household decision-maker.

Alternatively, others claim that it originated in Wales. In Wales, Roma people’s marriages were not recognized by the church, so they would have “Besom Weddings,” referring to a type of broom. At these weddings, couples would jump over the broom without touching it to get married; and to annul the marriage, couples would jump over the broom backward as a way to end their partnership. Some accounts even note that brooms were placed as a hurdle for couples to jump over separately, and if the broom fell—or if either party did not make it over the broom—the union was considered "not meant to be" and the wedding was canceled.

As it pertains to jumping the broom within the African American community, brooms were used during slavery in the United States as a way for enslaved people to get married since they could not legally wed in the country. However, it's important to note that there are two accounts for this origin. It's generally reported that people who were enslaved decided to jump the broom themselves since brooms were typically available. On the contrary, others argue that enslavers would force enslaved people to get married in this manner. Once slavery ended, though, some Black people decided that they would continue to jump the broom if an officiate was not readily available, and make their marriage legal at a later date. This was due to the fact that formerly enslaved people did not feel the need to get legally married and believed jumping the broom years prior was valid enough.

Lastly, in regards to the non-secular significance of this tradition, within Christian ceremonies, the broom handle represents God, the straw bristles signify the couple’s families, and a ribbon around the broom symbolizes the ties that bind the couple. In Pagan ceremonies, it is said that the broom handle represents the male phallus and the bristles represent female energy.”

The headdresses pictures are of West African origin.

This is the “only known painting of its era that depicts African American by themselves, concerned only with each other.”

What do we know of the painter & plantation owner John Rose? In 1775, he was Clerk of the Court of Commons Pleas in Beaufort, SC. By 1795, he owned a lot of land in Beaufort and a rural tract of land (813 acres) on the Coosaw River in Prince William Parish. As mentioned above, John Rose used slave labor on his plantation and had at least 50 slaves.

In her research, Dr. Susan Shames examines the landscape beyond the figures and asks some interesting questions: the river in the middle ground suggests that perhaps John Rose owned property on both sides “of the natural boundary.” And with this in mind, are the dwellings in the background on John Rose’s property or a neighbor’s? There appears to be a manor or mansion house, outbuildings including stables, and what appear to be a row of slave dwellings from the main plantation area.

John Rose moved to the Dorchester area in present-day Colleton County in 1795, and died in 1820 in Charleston after a fall from a horse.

Rose left his “The Old Plantation” painting in his will to his son-in-law Thomas Davis Staff. According to Dr. Susan Shames, the painting remained in the family for more than 100 years until it was sold at auction in 1929.

The painting was purchased by in 1935 by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, the wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr. , the son of John D. Rockefeller Sr., the founder of Standard Oil. Her father was Nelson W. Aldrich, who served as a senator from Rhode Island.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller transferred the painting to Williamsburg, Virginia where it has been given to Colonial Williamsburg and is currently held in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg.

Interestingly, there is another painting from this time period that may also be attributed to John Rose — the watercolor (in the Gibbes Museum collection) called Tranquil Hill (painted between 1805-1820).

On the bottom, the painting says: “Tranquil-Hill The Seat of Ann Waring, Near Dorchester.”

While Tranquil Hill and The Old Plantation are stylistically different, Dr. Susan Shames has connected the fact that John Rose and his family moved from Beaufort to Dorchester in 1795, which is where Ann Ball Waring lived.

Going even deeper, John Rose and Ann Ball Waring attended the “same small church, lived in close proximity, and clearly traveled in the same social circles.”

Dr. Susan Shames researched the watermark on the painting, which suggests the painting was made after 1805, when Rose lived in Dorchester.

All of the above supports Dr. Susan Shames’ theory that John Rose painted as a hobby and likely painted the scene at Tranquil Hill as a gift for his friend and neighbor Ann Ball Waring.

Upon learning this information, my initial gut reaction was that if John Rose made a watercolor of this intricacy, he must have had very strong feelings towards Ms. Ann Ball Waring. Perhaps he was courting her through his art? Alas, it was not so. Ms. Ann Ball Waring was married to a man named John Ball. But that would have been an exciting colonial era romantic twist, don’t you think?

If you voted just “OK” on the newsletter today, I want to hear from you! Reply to this email and send me your feedback. :)

➳ Sources — The Mystery of "The Old Plantation" Painting

“‘Jumping the Broom’: The Wedding Tradition With African Roots.” Oprah Daily, 4 Feb. 2022, https://www.oprahdaily.com/life/relationships-love/a35992704/jumping-the-broom-wedding-tradition-history-origins/. Accessed 30 May 2025.

“Jumping the Broom: History and Meaning Behind the Wedding Tradition.” Brides, https://www.brides.com/jumping-the-broom-5071336. Accessed 30 May 2025.

“The Old Plantation.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Old_Plantation. Accessed 30 May 2025.

“The Old Plantation, ca. 1790–1800.” Gibbes Museum of Art, https://www.gibbesmuseum.org/news/?attachment_id=1708. Accessed 30 May 2025.

Roberts, Dorothy. Slave Marriages and the Problem of Intimate Violence. University of Massachusetts Amherst, ScholarWorks, https://scholarworks.umass.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/aa9ce2b0-fda0-4724-b451-957f21951054/content. Accessed 30 May 2025.

“The Old Plantation.” Encyclopedia Virginia, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/4333hpr-b5deaccd6d628b6/. Accessed 30 May 2025.