#69: Medicine on antebellum plantations, Hampton Plantation, and the "Toll of War" exhibit

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #69 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

Here’s a little welcome/update audio message:

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

zachary.demoya

lplane2000

beaclsy1

cjeason

garrick.irwin

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Ongoing exhibition | “The Toll of War - Grief & Mourning” | The Newberry Museum | Newberry, SC | FREE Admission

“‘The Toll of War’ is a traveling exhibit by the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. The exhibit features both the physical and emotional effects of the war on those who lived through it. The motto of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine is “divided by conflict, united by compassion,” in reference to how doctors, both Northern and Southern, struggled to aid the wounded, and often shared information across the battle lines to help aid the injured.

The Newberry Museum has supplemented the traveling exhibit with our local story entitled “Newberry Veterans: Medical Care, Trauma, and Recovery.” This exhibit delves into many aspects of the experiences of Civil War veterans, those wounded, their families, and those who cared for them during and after the war. In the realm of physical wounds, the exhibit examines the types of injuries Civil War soldiers faced and how they were treated.

Coming Soon! This exhibit will feature a Medicinal Garden in our recently renovated Courtyard curated by the Nosegay Garden Club. The garden will feature many plants that would have been used by both medical professionals and housewives during the mid-1800s. Look for the Medicinal Garden’s open date to be announced in the upcoming weeks.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

What was medicine like on plantations in the antebellum South?

Listen to this section in the audio voiceover below!

In antebellum South Carolina, there were few doctors and because people lived so far apart, one could not rely on doctors as we do today. Instead, plantation masters and mistresses, and enslaved workers, often had to rely on themselves and what they learned from “home-made remedies, folk beliefs, conjuring, and superstition to help meet their medical needs.”

The South only had 5 medical colleges before 1845, and medical students “spent only 1-2 years working with a preceptor and attended only a few lecture courses to complete their medical training.” Some southern physicians received their training in the North or Europe.

When they couldn’t rely on “regular” doctors, some southerners relied upon “irregular doctors such as homeopaths, empirics, and eclectics.”

Antebellum Southerners were subject to the same illnesses of Northerners such as tuberculosis, diphtheria, whooping cough, yellow fever, malaria, worms, yaws (an infection of the skin, bones, and joints), and cholera. Malaria was particularly harsh for Southerners who lived near mosquito-ridden marshes and swamplands — and especially for slaves who worked on rice plantations and were expected to work in the water day in and day out.

During this time, medicine also gave way to horrible, racist theories about the enslaved. One southern physician Dr. Samuel Cartwright believed that “the size of black people’s brains was a 9th or 10th less than other races of men.” Other doctors theorized that there were particular diseases only slaves had including “Drapetomania” (mental disease that spurred slaves to run away) and “Cachexia Africana” (dirt eating).

The most common method of treating diseases in the antebellum South was through “depletion” which involved “draining the body of what was believed to be harmful substances” through “bleeding, sweating, blistering, purging, or vomiting.” Bloodletting, though considered a “cure,” if not properly administered, could be as deadly as the illness.

Many were skeptical of doctors and relied instead on medical manuals and their own home-grown methods of treatment. Here are some names of some of the manuals:

Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves (1803)

The Planter’s and Mariner’s Medical Companion (1807)

The American Medical Guide for the Use of Families (1810)

Letters to Ladies, Detailing Important Information, Concerning Themselves and Infants (1817)

Gunn’s Domestic Medicine (1830)

It was “in the planter’s interest to take a proactive role in the medical care of slaves.” Health conditions for slaves were also discussed in medical journals so that slave owners could get the most from their work force.

Writing in 1847, J. D. B. DeBow (slave owner and founder of DeBow’s Review) suggested:

“Houses for negroes should be elevated at least two feet above the earth, with good plank flooring, weather proof, and with capacious windows and doors for ventilation, a large fireplace, and wood convenient. A negro house should never be crowded…. Good water is far more essential than many suppose…. In relation to food a word might be ventured; the point is to provide enough.”

If a slave was very sick, they were often sent to the “sick house” where usually the plantation mistress, and her slave servants, could supervise and help them heal.

The plantation mistresses were not only chiefly responsible for the health of their own families, but the health of their enslaved workers as well. This was a demanding role to play, and the stress was sometimes too much for some women. Some medical journals of the time gave treatments for “Female Derangement and Disease.”

Women’s reproductive healthcare was woefully misunderstood, and there was significant mortality caused by childbirth.

Large families were also common in the South and frequent childbirths took a toll on women’s health. Many women feared childbirth because they thought they, or their child, would die in the process. Many complications could occur including: “childbed” fever, inability to breastfeed the child, prolapse of the uterus, to name a few.

Pregnant enslaved women faced the same medical fears and complications as white women, but it is believed that “one half of slave women’s pregnancies resulted in still births.” These still births were likely caused by the physical demands of slave labor on pregnant women’s bodies.

Furthermore, if female slaves did give birth, slaveholders demanded that that “women who had just delivered babies return to the fields almost immediately; pregnant women were forced to work; and pregnant women were whipped.”

Plantation kitchen recipe books, or “receipt books” as they were called, had many home remedies made on plantations using southern native plants and roots. For example, The Confederate Receipt Book provided this remedy for asthma:

“Take the leaves of the stramonium (or Jamestown weed) dried in the shade, saturated with a pretty strong solution of salt petre, and smoke it so as to inhale the fumes. It may strangle at first if taken too freely, but it will loosen the phlegm in the lungs. The leaves should be gathered before frost.”

Enslaved workers had their own remedies as well — they “merged European, Native American, Caribbean, and African medical folklore to create their own blend of medicine.”

Sometimes healthcare became supernatural within the slave community. Conjurers, also known as the hoodoo or root doctor, “relied upon the supernatural as well as plants, herbs, and roots to heal or cause harm to individuals.” Conjurers were also known to use “trickery, magic, spells, violence, persuasion, intimidation, mystery, gimmicks, fear and some medical practices,” which helped the conjurer rise to a level of importance within the slave community.

The power of the conjurer could be used against an oppressive slave master. In the 1845 autobiography of Frederick Douglass, he explained how an acquaintance suggested that he carry “a certain root in his right pocket” that would protect him from beatings by his master, Mr. Covey. Douglass took this advice and found that in confrontations with Covey, the confrontations usually went in Douglass’s favor and eventually stopped. Douglass indicated that this experience with the root was the “turning point in my career as a slave.”

In these many ways, healthcare on plantations of the antebellum South employed the efforts of the whole community. When the physician wasn’t available, which was often the case, the members of the plantation, black and white, worked together to administer remedies and heal the sick.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you know that the Hampton Plantation house is one of the earliest examples of the use of the giant portico in American domestic architecture?

Listen to this section in the audio voiceover below!

Yesterday’s newsletter discussed the Hampton Plantation as a site in the Underground Railroad. Today, let’s discuss more of its history.

Built between 1730-1750, the Hampton Plantation in McClennanville, SC served as the home to the prominent Horry, Pinckney, and Rutledge families. Today, it is the Hampton Plantation State Historic Site where visitors can explore the grand plantation home and grounds.

Hampton Plantation today consists of just under 300 acres of land on the banks of Hampton Creek, a tributary of the Santee River in northern Charleston County, South Carolina, west of United States Route 17.

This was a rice plantation and at the height of its production, 340 slaves worked the property. The historic site also features “dikes created by the enslaved Africans for the production of rice…Some 25 rice fields once stretched across the land as far as the eye could see.”

The rice grown in this period was called “Carolina Gold.”

The structure includes “one of the earliest examples of the use of the giant portico in American domestic architecture, and Hampton is South Carolina’s finest example of a large two-and-one-half story frame Georgian plantation house.”

The grand Georgian house visitors see today is an evolution from many years of ownership and renovations.

The original core of the house was built in 1735 by Noe Serre, a French Huguenot, and was a central-hall two-story structure. The property was acquired in 1757 by Daniel Horry, who greatly expanded the building, “adding a two-story ballroom on one side, and a master bedroom suite on the other.” In order to ensure symmetry of appearance, Horry had false shuttered windows placed on the front walls of these additions. The front portico is the last major alteration made to the building.

George Washington visited the Horry family on his “great American tour” and prevented the family from cutting down the massive oak tree that stands in front of the home, and still stands today — earning its name, the Washington Oak.

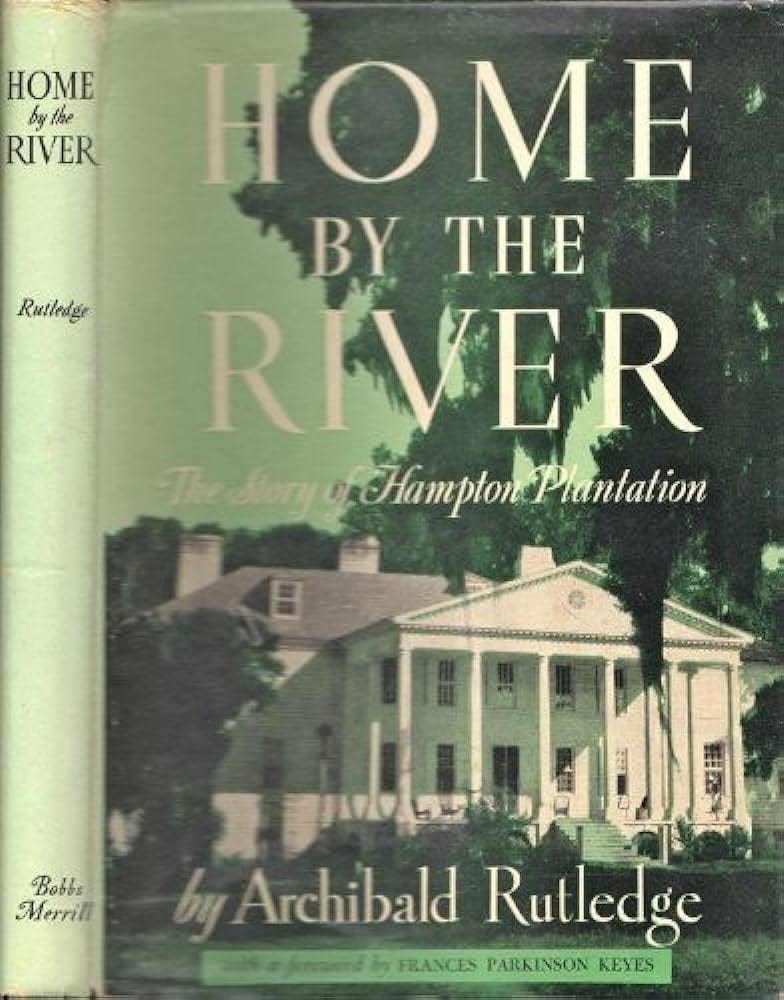

The last private owner of the property was Archibald Rutledge, who was also South Carolina’s first poet laureate. Rutledge's 1941 book, titled Home by the River, describes his 1937 return to Hampton Plantation after a 33-year absence. Included is the tale of his efforts to restore the plantation and its 209-year-old house, all of which had been in his family since 1686.

In his book, My Reading Life, South Carolina author Pat Conroy recalls meeting Rutledge at Hampton Plantation when Conroy was an aspiring writer still in his teens. Rutledge discussed the process of writing as well as the history of the Plantation with young Conroy.

The state purchased the property from the Rutledge family in 1971.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Have you been to Hampton Plantation? We would love to know about your experience. Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“There was Hampton on the shore, white and stately as of yore,

Seen glimmering through a vista as of years long gone before;

then the desolate Montgomery of those who come no more.”

—The Song of the Santee by Archibald Rutledge

Antebellum Medicine article sources:

Sullivan, Glenda. Plantation Medicine and Health Care in the Old South. Legacy Student Research Journal, Southern Illinois University, 2010, https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=legacy. Accessed 19 Apr. 2024.

Hampton Plantation article sources:

Casto, Maddie. “The History of Hampton Plantation State Historic Site | Coastal Expeditions Blog.” Coastal Expeditions, 9 June 2021, https://www.coastalexpeditions.com/blog/the-history-of-hampton-plantation-state-historic-site/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2024.

“Discover the History of the Hampton Plantation.” South Carolina Tourism Official Site | South Carolina Vacations, https://discoversouthcarolina.com/articles/discover-the-history-of-the-hampton-plantation. Accessed 19 Apr. 2024.

“Hampton Plantation.” National Register Sites in South Carolina, http://www.nationalregister.sc.gov/charleston/S10817710016/index.htm. Accessed 19 Apr. 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!