#99: John C. Calhoun, The Liberty Tree, and an Arsenal Hill Walking Tour

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 21st, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #99 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

ridgeview1

mattwp18

ctprice92

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Sunday, July 21st at 1:00 pm | “Arsenal Hill Walking Tour” | Tour begins at Arsenal Hill Community Center | Columbia, SC | $5 for members, $10 for non-members

“Join Historic Columbia for a stroll through the Arsenal Hill neighborhood, located at the highest elevation within downtown. Named for the military academy established here in 1842, Arsenal Hill became a desirable residential area for white elites during the antebellum era and then for middle- and working-class Black residents during the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Participants will learn how these residences, combined with spiritual, educational, and governmental institutions, resulted in an eclectic mix of architecture as well as dynamic community histories. The tour will last approximately 75 minutes and includes standing and walking approximately one mile on neighborhood sidewalks. The tour will begin and end at Arsenal Hill Community Center.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Did you know that John C. Calhoun is one of South Carolina’s most influential politicians in the state’s history?

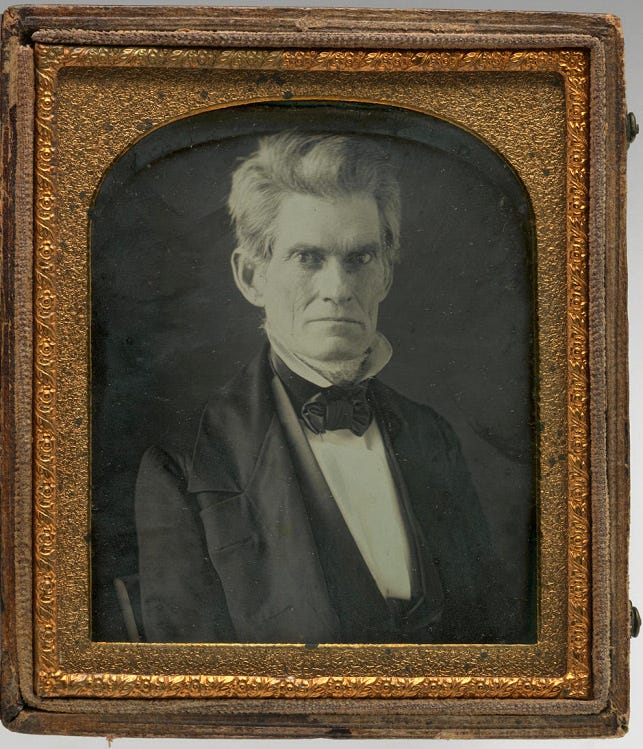

John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) of South Carolina was one of the most influential politicians in the United States and a leading voice for the South during the antebellum era.

He served as a U.S. Representative, Secretary of War, Vice President and Secretary of State, and had a long career in the U.S. Senate, during which he emerged as an outspoken defender of states’ rights and the institution of slavery.

John Caldwell Calhoun was born into a large Scots-Irish family on a plantation in rural South Carolina on March 18, 1782.

His father, Patrick Calhoun, fought in the Revolutionary War and was elected to the South Carolina legislature after it ended.

Patrick died when John was 13, and “his three older brothers helped pay for his education.”

Calhoun eventually attended Yale University in Connecticut, graduating in 1804. He studied briefly at Litchfield Law School in Connecticut before returning to South Carolina, where he settled in Abbeville.

In 1808, not long after taking the bar examination, Calhoun was elected to the South Carolina legislature from his new district. He won election to the U.S House of Representatives two years later and took his place among a group of congressmen known as “War Hawks,” who denounced British aggression against American ships and supported measures that would lead to the War of 1812.

In 1811, Calhoun married Floride Bonneau Colhoun (yes, spelled with the “o”), a cousin of his father and a member of one of South Carolina’s most prominent families. With this marriage, Calhoun joined the state's elite planter class.

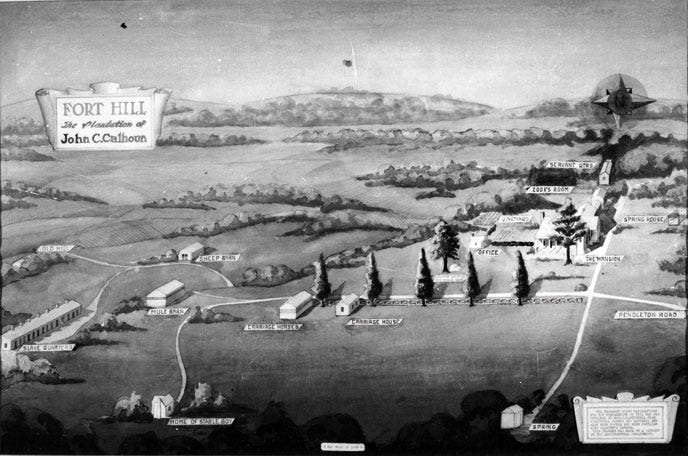

John and Floride Calhoun purchased what would become known as their Fort Hill plantation in 1825. The home and the property would eventually be inherited by Calhoun’s daughter Anna Calhoun and her husband Thomas Green Clemson. In his 1888 will, Thomas Clemson bequeathed more than 814 acres of the Fort Hill estate to the State of South Carolina to establish an agricultural college, which became Clemson University. Clemson’s will also stipulated that the Fort Hill plantation house (now referred to as the John C. Calhoun house) shall “never be torn down or altered.” The John C. Calhoun house still stands in the middle of Clemson’s campus.

After the Treaty of Ghent in 1815, Calhoun played an important role in the “ambitious nation-building efforts” led by his fellow congressman Henry Clay. These included the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States, federally funded internal improvements and high protective tariffs to encourage the growth of American manufacturing.

Calhoun left Congress in 1817 to become U.S. Secretary of War in the administration of James Monroe. In that role, he “strengthened the nation’s military, reorganizing the armed forces as well as the new U.S. Military Academy at West Point. An early presidential candidate in 1824, he easily won election as vice president after supporters of both Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams backed him. (At the time, presidential and vice-presidential candidates did not run on a single ticket.)”

The presidential race that year was decided in the House of Representatives, which controversially voted in favor of Adams despite Jackson's victory in the popular vote.

Outraged by this “corrupt bargain,” Calhoun increasingly opposed Adams' staunch federalist policies.

With Andrew Jackson's presidential victory as leader of the new Democratic Party in 1828, Calhoun was again elected as vice president.

That same year, passage of a high protective tariff—known in the South as the Tariff of Abominations—sparked fierce resistance in South Carolina. At the urging of the state legislature, Calhoun wrote an anonymously published pamphlet called “Exposition and Protest” which argued that states had the right to nullify any action by the federal government they considered unconstitutional, and even to secede from the Union if necessary.

Early in Jackson’s first term, a social scandal rocked Washington and drove a wedge between Calhoun and Jackson. Floride Calhoun (Calhoun's wife) played a leading role in ostracizing Peggy O’Neal Timberlake Eaton, the new wife of Jackson’s new Secretary of War John Eaton, due to “rumors about her questionable morals and shady past.” While Andrew Jackson—whose late wife, Rachel, had been the victim of similar attacks—supported the Eatons, Calhoun backed his wife, causing growing tensions within the cabinet.

After Congress adopted another high tariff in 1832, South Carolina’s legislature used Calhoun's arguments to declare the tariff null and void. President Jackson refused to accept this threat to the sovereignty of the Union, asking Congress to pass a Force Bill to empower federal troops to collect tariffs in South Carolina.

Calhoun's relationship with Jackson—already strained due to the Peggy Eaton scandal, also known as the "Petticoat Affair"—deteriorated completely during this Nullification Crisis, and Calhoun resigned in late December 1832 to take a seat in the U.S. Senate, where he would serve for the next 9 years.

In his three-volume biography of Jackson, author James Parton summed up Calhoun's role in the Nullification crisis: "Calhoun began it. Calhoun continued it. Calhoun stopped it."

Calhoun remained officially a Democrat, but he strongly opposed the party's policies under Jackson and Jackson's successors. He argued that “it didn't do enough to protect states' rights or slavery, both of which he championed in the Senate.”

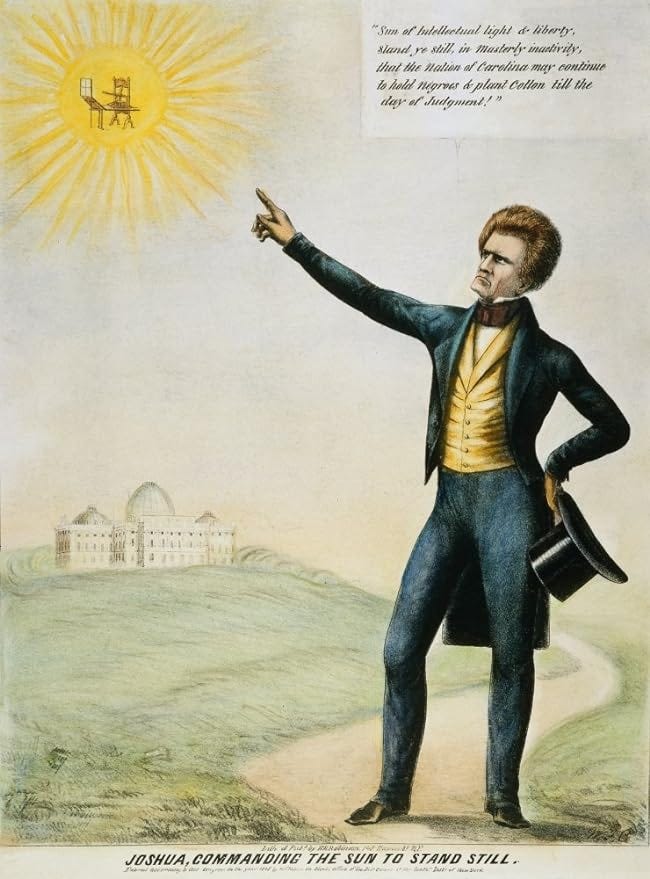

Calhoun was a slaveholder himself and a strong defender of the institution against attack by abolitionists, calling it "a positive good" during a Senate debate in 1837.

As well as providing an intellectual justification of slavery, Calhoun played a central role in devising the South's overall political strategy. According to historian Ulrich B. Phillips:

“[Calhoun's] devices were manifold: to suppress agitation, to praise the slaveholding system; to promote white Southern prosperity and expansion; to procure a Western alliance; to frame a fresh plan of government by concurrent majorities; to form a Southern bloc; to warn the North of the dangers of Southern desperation; to appeal for Northern magnanimity as indispensable for the saving of the Union.”

In 1843, Calhoun resigned his Senate seat and returned to South Carolina to mount a final run for the presidency. But his campaign never gained momentum, and in early 1844 he accepted the post of Secretary of State in John Tyler’s cabinet.

In 1845, Calhoun was again elected to the Senate, where he became a member of the influential “Great Triumvirate,” along with Clay and Daniel Webster.

As sectional tensions continued to heat up in the antebellum era, Calhoun led efforts to maintain the balance of power between free and slave-holding states and protect the rights of Southern slave-owners.

Calhoun opposed the U.S. war with Mexico in 1846, as well as the Wilmot Proviso, the unsuccessful effort to ban slavery in the lands acquired in the Mexican-American War.

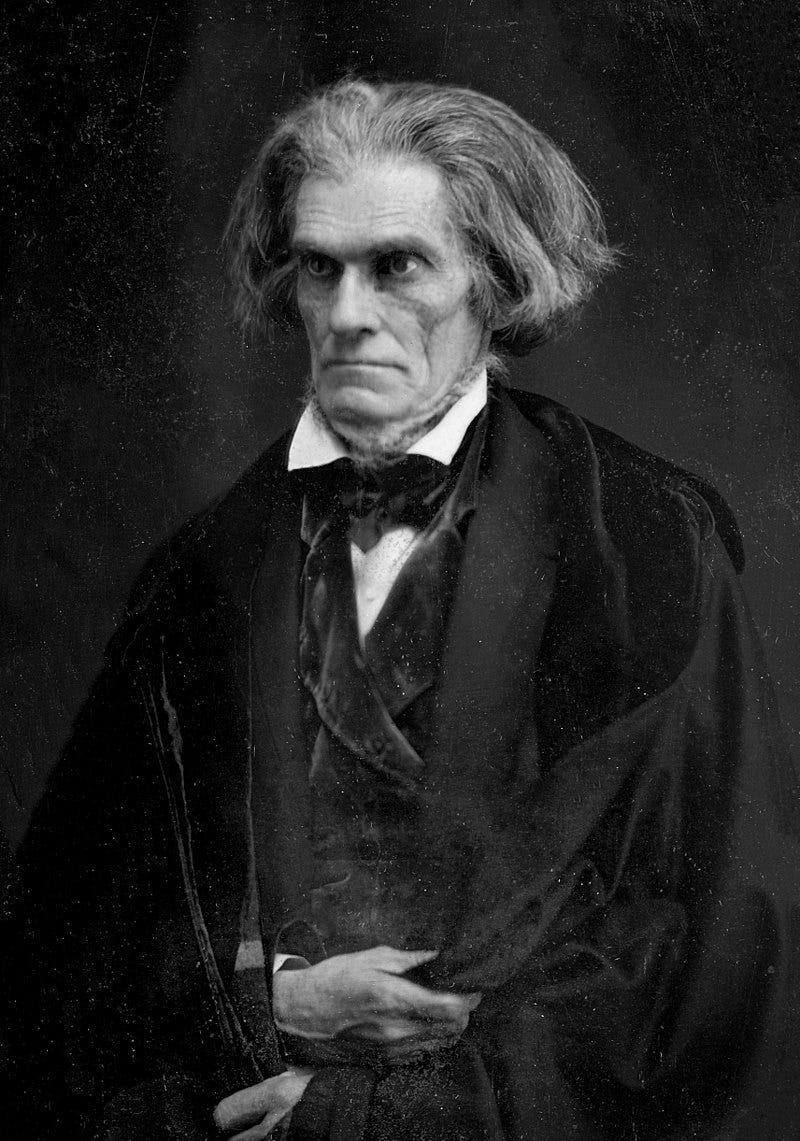

By January 1850, when Clay introduced compromise measures designed to settle the sectional dispute over slavery, Calhoun was gravely ill with tuberculosis.

In his last Senate speech, which another senator had to read aloud, Calhoun attacked the compromise measures, “arguing that the nation was heading for disunion due to the continued domination of Northern over Southern interests.”

Before the Compromise of 1850 was concluded, Calhoun died on March 31, 1850 at the age of 68.

With the Civil War barely a decade away, a rising group of radical Southern politicians known as “fire-eaters” continued to embrace and build on Calhoun’s views on nullification, states’ rights and slavery, pushing the South ever closer to secession.

Writing more than 30 years after Calhoun's death, James G. Blaine (Republican politician who represented Maine in the United States House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876) portrayed Calhoun as a mix of personal integrity and wrongheaded ideology:

“Deplorable as was the end to which his teachings led, he could not have acquired the influence he wielded over millions of men unless he had been gifted with acute intellect, distinguished by moral excellence, and inspired by the sincerest belief in the righteousness of his cause. History will adjudge him to have been single-hearted and honest in his political creed. It will equally adjudge him to have been wrong in his theory of the Federal Government, and dead to the awakened sentiment of Christendom in his views concerning the enslavement of man.”

In recent years, monuments and buildings named after John C. Calhoun have been the cause of controversy and debate.

In 2017, Calhoun’s alma mater Yale University decided to remove Calhoun’s name from one of their internal colleges and rename the college for another alumna Grace Murray Hopper. The decision was made by Yale President Peter Salovey and the university’s board of trustees:

“The decision to change a college’s name is not one we take lightly, but John C. Calhoun’s legacy as a white supremacist and a national leader who passionately promoted slavery as a ‘positive good’ fundamentally conflicts with Yale’s mission and values.”

There was also a monumental statue dedicated to John C. Calhoun in Charleston, In 2020, the monument was taken down in a unanimous vote by Charleston city council. On June 23, 2020, after a 17-hour removal effort, the John C. Calhoun statue was taken down from its “115-foot perch.” The current location of the John C. Calhoun bust is undisclosed. Some groups have called for the statue to be placed inside a museum. However, the Charleston Museum declined the city's request. As of October 2020, the statue has still not been claimed by any museum or historical society.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you know that Charleston’s The Liberty Tree was an early meeting place for the Revolutionary cause?

In Revolutionary times, Charleston's Liberty Tree was the meeting place for the city's sect of the Sons of Liberty, an organization that advocated for the American Revolution.

The oak tree, at the time located in “Mr. Mazyck’s cow pasture,” was chosen by William Johnson Sr., father of future Supreme Court Justice, William Johnson, Jr., as a meeting place.

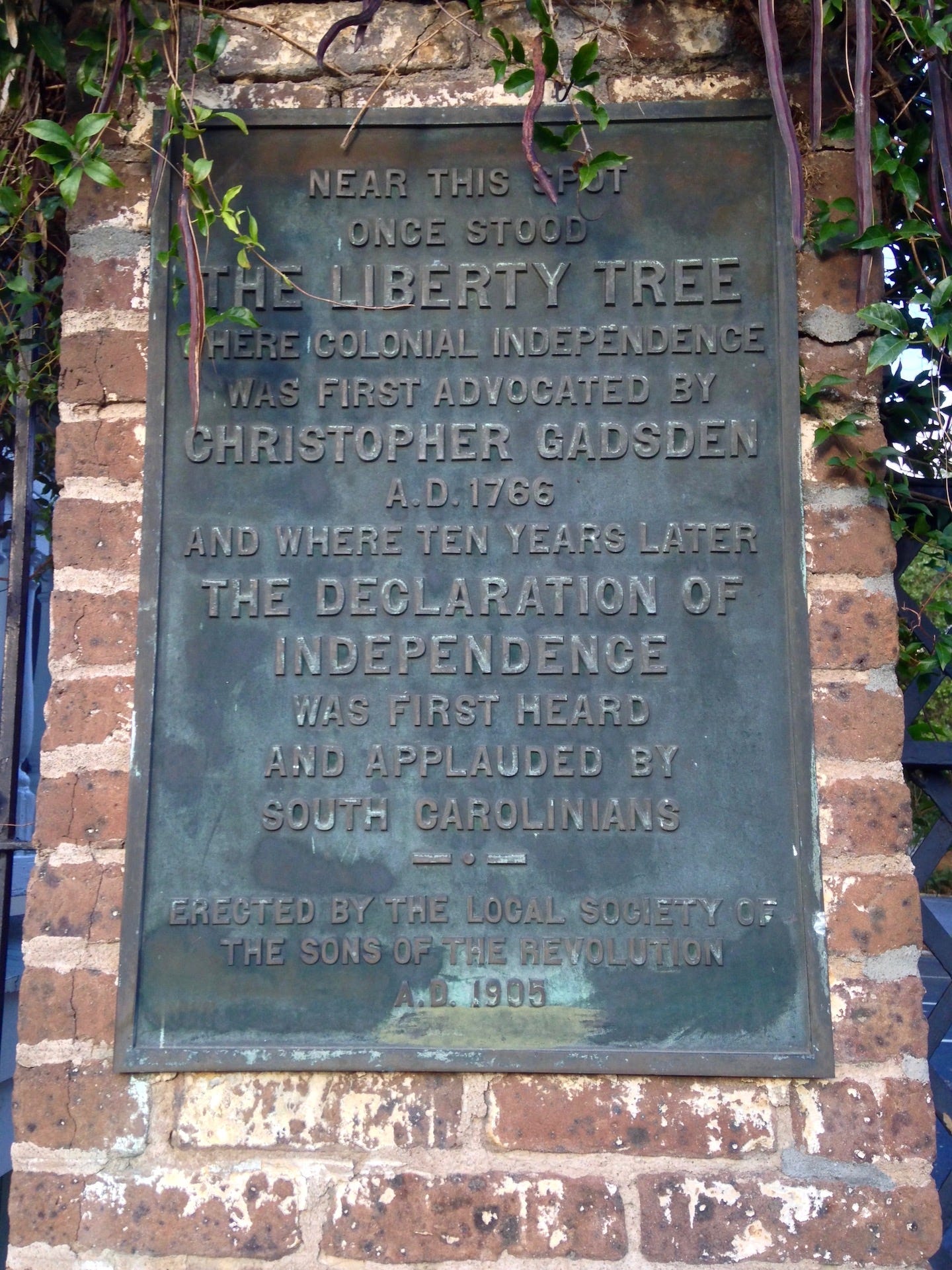

It was where Christopher Gadsden, who is considered "Charleston's Sam Adams," advocated for American independence.

In 1820, one of the Revolutionaries named George Flagg (1741-1824) wrote:

“On this occasion the above persons invited Mr. Gadsden to join them, and to meet at an oak tree just beyond Gadsden’s Green [Ansonborough], over the Creek at Hampstead, to a collation prepared at their joint expense for the occasion. Here they talked over the mischiefs which the Stamp Act would have induced, and congratulated each other on its repeal. On this occasion Mr. Gadsden delivered to them an address, stating their rights, and encouraging them to defend them against all foreign taxation. Upon which joining hands around the tree, they associated themselves as defenders and supporters of American Liberty, and from that time the oak was called Liberty Tree—and public meetings were occasionally holden [sic] there.”

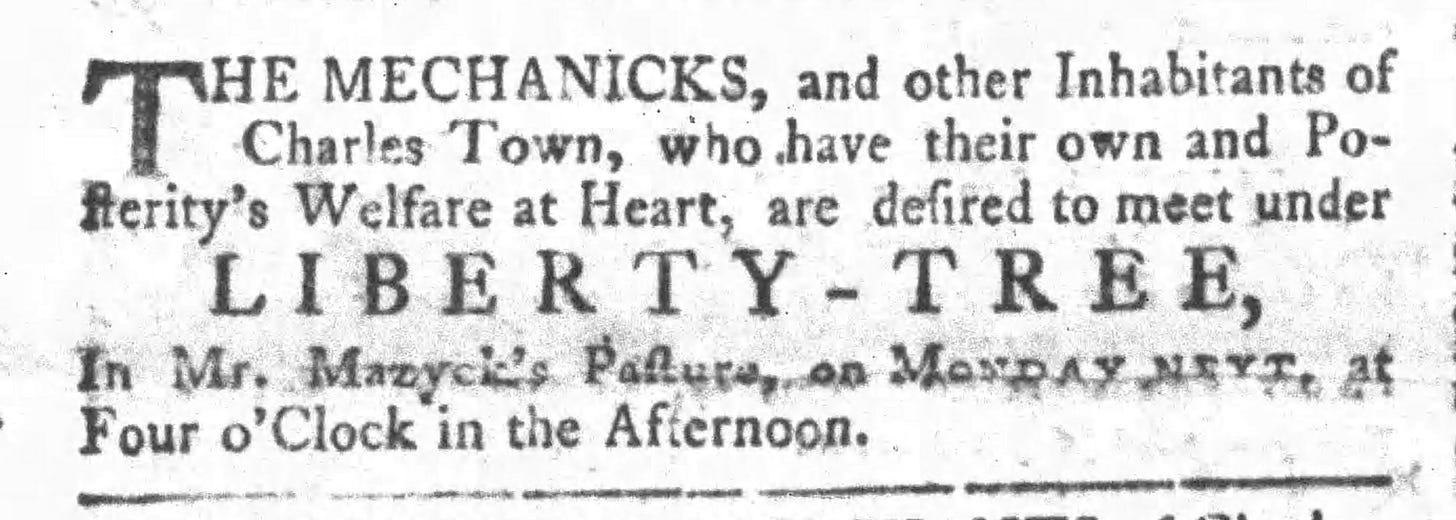

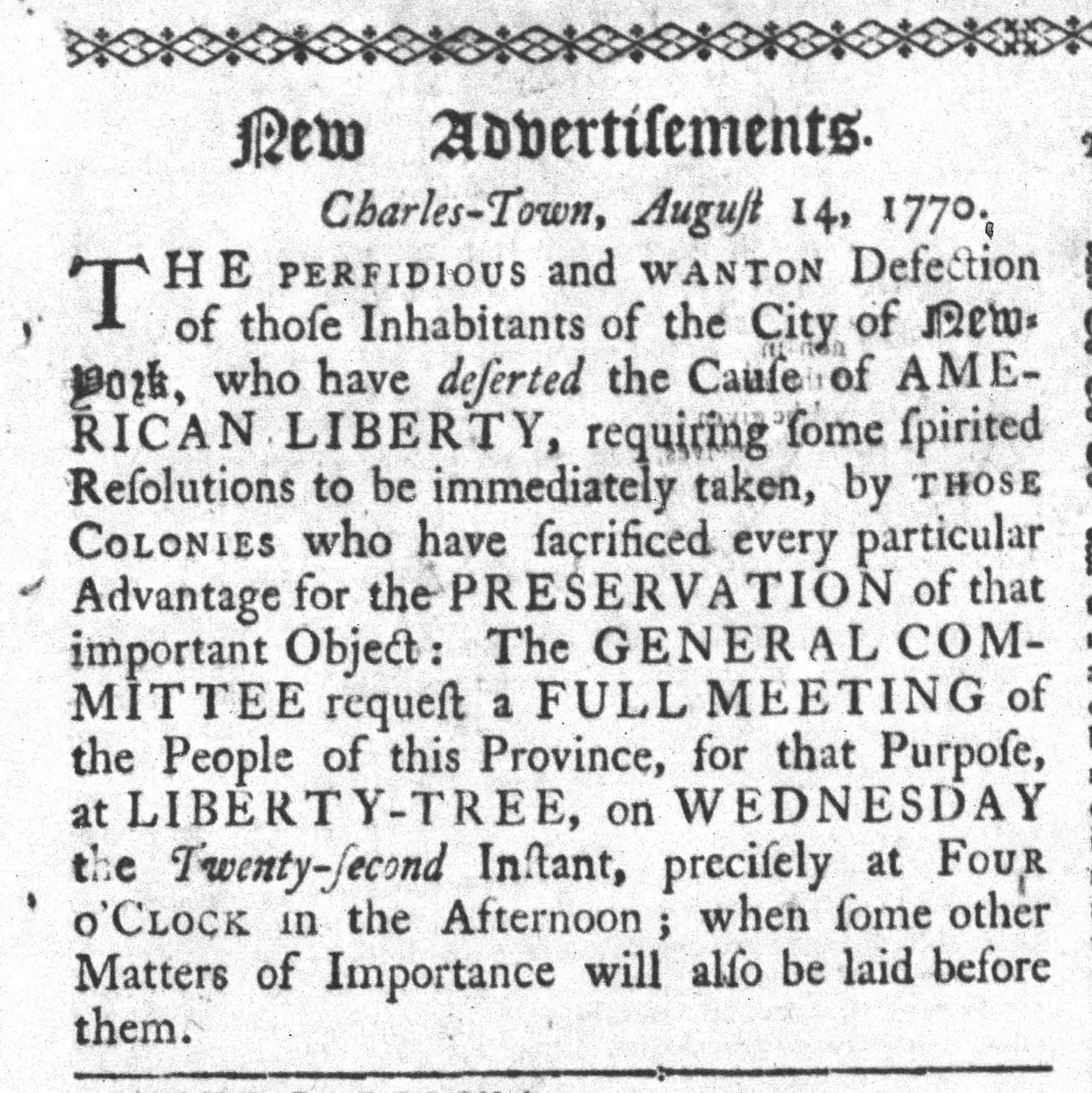

Here are some images in the local paper where Patriot meetings were advertised under the tree:

On September 18, 1769, an anonymous poem “On Liberty-Tree” was published in the South-Carolina Gazette. Here is an exciting excerpt from that poem:

“Yet here, beneath thy fav’rite Oak,

Thy Aid will all thy Sons invoke.

Oh! If thou deign to bless this Land,

And guide it by thy gentle Hand,

Then shall America become

Rival, to once high-favour’d Rome.”

It was the site where news of the United States Declaration of Independence was announced to Charleston citizens in 1776.

The Liberty Tree was utilized from the late 1760s until 1780.

When the British occupied Charleston from 1780 to 1782, they cut down the Liberty Tree and burned its stump to prevent it from becoming a patriot shrine. But they didn’t think about the tree’s roots…

After the war, Judge William Johnson retrieved a root and had it made into cane heads. One of them was given to Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence.

In 1905, a historical marker was placed near the tree's former location on Alexander Street by Local Society of the Sons of the Revolution.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ SC History Quote

“Here LIBERTY, divinely bright,

Beneath thy Shade, enthron’d in Light,

Her beaming Glory does not impart

Around, and gladdens ev’ry Heart.”

—Sept. 18, 1769, another excerpt from the Liberty Tree poem that was published in the South-Carolina Gazette

John C. Calhoun article sources:

“African-Americans at Fort Hill.” Clemson University, https://www.clemson.edu/about/history/properties/fort-hill/african-americans.html. Accessed 15 May 2024.

“John C. Calhoun.” Wikipedia, 15 May 2002, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_C._Calhoun. Accessed 15 May 2024.

“John C. Calhoun - Biography, Facts & Significance.” HISTORY, https://www.history.com/topics/us-government-and-politics/john-c-calhoun. Accessed 15 May 2024.

“Yale Changes Calhoun College’s Name to Honor Grace Murray Hopper | YaleNews.” YaleNews, 11 Feb. 2017, https://news.yale.edu/2017/02/11/yale-change-calhoun-college-s-name-honor-grace-murray-hopper-0. Accessed 15 May 2024.

Liberty Tree article sources:

“Remembering Charleston’s Liberty Tree, Part 1 | Charleston County Public Library.” Charleston County Public Library, 26 June 2020, https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/remembering-charlestons-liberty-tree-part-1. Accessed 15 May 2024.

“Charleston Key in Revolutionary.” Statehouse Report, https://www.statehousereport.com/2020/10/02/brack-charleston-key-in-revolutionary-civil-wars/. Accessed 15 May 2024. Accessed 15 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!