#70: Moonshine & Prohibition, the Florence Stockade, and annual Living History Day at Hampton Plantation

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #70 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

jpatrickarm

lovsin

frherr

jonesinginsc

rkwillms

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, April 27th, 11:00 am - 3:00 pm | “Annual Living History Day at Hampton Plantation: Step Back in Time” | Hampton Plantation State Historic Site | McClennanville SC | FREE Admission

“Step back in time at Hampton Plantation with our annual living history day! Come learn about the building of Battery Warren in 1862 on the South Santee River, Confederate pensions for Black soldiers in the 1920s and more with our park rangers, guest speakers, and reenactors. Food will be available for purchase, and admission to the event includes the tour of the mansion house.

*Guest speaker Dr. Walter Curry will present on Black Confederate pensioners at 1pm.

*Reenactors will be encamped between 11am and 3pm.

*The house will be open to tour between 12pm and 3pm.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Did you know that Hell Hole Swamp in Berkeley County, SC was the hotbed of illegal moonshine in the Prohibition era South Carolina?

The Prohibition era lasted from 1920-1933 when the sale, manufacture, and distribution of alcohol was illegal in the United States.

The law, however, didn’t stop certain South Carolinians from concocting their home home-brewed whiskey, called “moonshine.”

While bootleggers were “active across the state during Prohibition,” we are going to turn back to a newsletter topic from a few days ago and go back to a place — with an amazing name — that served as the hotbed of illegal alcohol in that time: Hell Hole Swamp in Berkeley County, SC.

Fervently dry Governor John G. Richards said in 1929: “Berkeley County is a festering sore in South Carolina.”

State and federal agents made repeated raids in Hell Hole swamp in an attempt to “clean up” the area of its bootleggers and moonshine, but their attempts were in vain. The corn-liquor trade flourished.

Mason jars filled with Hell Hole Swamp moonshine “were shipped by the boxcar-full to Al Capone’s Chicago, lined the shelves of speakeasies in New York, and filled the teacups at the blind tigers in Columbia, Savannah, and Atlanta. Closer to home, it kept the citizens of Charleston in the afternoon cocktails to which they were long accustomed. As one elder matriarch of Holy City society quipped, ‘Of course we continued to drink during Prohibition. I don’t know where Daddy bought the liquor. It was just delivered to the back porch every morning with the milk.’”

Hell Hole Swamp was once a location of early rice plantations in South Carolina, where early settlers became rich from the crop. The Civil War changed everything however, and by the 1920s, the former rice plantations were in ruins and the rice fields reverted back to swamps. The people who remained in the area were “a hard, unkempt, and illiterate race, ignorant and superstitious, but with a pioneer’s jealous love of freedom,” wrote 1930s Charleston newsman, Tom Waring Jr.

A Charleston Magazine “Moonshine Over Hell Hole Swamp” article from 2015 describes how people lived in the swamp:

“Hell Hole’s Prohibition-era inhabitants lived a hardscrabble existence in dogtrot cabins with tar-paper roofs and newspaper-covered interior walls. There was often an outhouse in the yard and a blue-tick hound asleep in the dirt under the sagging front porch. Behind the house, there was a garden where tomatoes, beans, and the essential stand of tall corn grew. And back yonder in the woods, hidden in the swamp, was the still.”

Families in the Hell Hole Swamp area had been making their own recipes of moonshine for generations, and during prohibition, business boomed and stills sprang up “like mushrooms,” which created competition amongst the location families.

A “kingpin” of the Hell Hole moonshine business was Glennie McKnight, who “furnished the equipment, sugar, and cornmeal to the men who ran the stills and took care of distribution and marketing.”

McKnight’s rivals were the Ben Villeponteaux clan, as well as the Wrights and Anderson families. A fued began between these families that turned violent. On May 8, 1926, there was an old-fashioned shootout between them on a highway near Moncks Corner. Glennie McKnight emerged from the shootout unhurt, but his brother Sammie was killed. Ben Villeponteaux was seriously wounded, as well as other members of his clan.

These bloody skirmishes at Hell Hole Swamp made national news and the Federal government decided to crack down further. They knew this time they had to hire someone “from the inside” and none other than moonshine kingpin Glennie McKnight became their insider informant.

On September 3, 1926, the Coast Guard cutter Yamacraw carrying 100 Federal agents entered Charleston Harbor. The following day, led by McKnight, they invaded Hell Hole Swamp. The raid took 2 days and resulted in the arrest of 33 men (including a sheriff and a deputy) and the destruction of 17 stills. Thousands of gallons of whiskey were poured onto the ground.

Yet even after this raid, the moonshine continued to pour out of Hell Hole Swamp! It turned out, not surprisingly, that that were was a secretive and corrupt system in the shadows that continued to transport the illegal alcohol out of the swamp — a system that even included the local Sherriff C.P. Ballentine and Berkley County State Senator Edward J. Dennis.

On July 24, 1930, when State Senator Dennis was walking to his office in Monck’s Corner, a man named W. L. “Sporty” Thornley shot the senator, who died the next day. In his testimony, Sporty Thornley claimed that moonshine kingpin Glennie McKnight had given him the gun and had promised him “cash, protection, and a house for his family.” McKnight was arrested and Sporty was convicted and given a life sentence.

Prohibition was repealed in 1933, and the hey day of Hell Hole Swamp was over. The “flow of big money” ended, but the backwoods stills still continued to produce their moonshine, and still do to this day.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you know that during the Civil War, Confederate Prisoner of War Camps had a death rate of 15%?

Thanks again to subscriber Sarah Wadsworth Bowers for another great newsletter topic suggestion for today!

One of the largest and most infamous Confederate prison camps during the Civil War was located in Florence, SC.

POW camps on both sides of the war were horrendous places, and studies have shown that Southern prison camps had a death rate of 15% and the Northern camps had a death rate of 12%.

Approximately 220,000 Southern soldiers became prisoners and 210,000 Northern soldiers became prisoners during the Civil War.

Thousands of soldiers were “paroled” and sent home after swearing an oath to refrain from further service. Other soldiers were exchanged for enemy prisoners. Thousands more underwent horrendous hardships in the prison camps, experienced dysentery, starvation, exposure to harsh weather. In the end, approximately 30,000 Northerners and 26,000 Southerners died in Civil War prison camps.

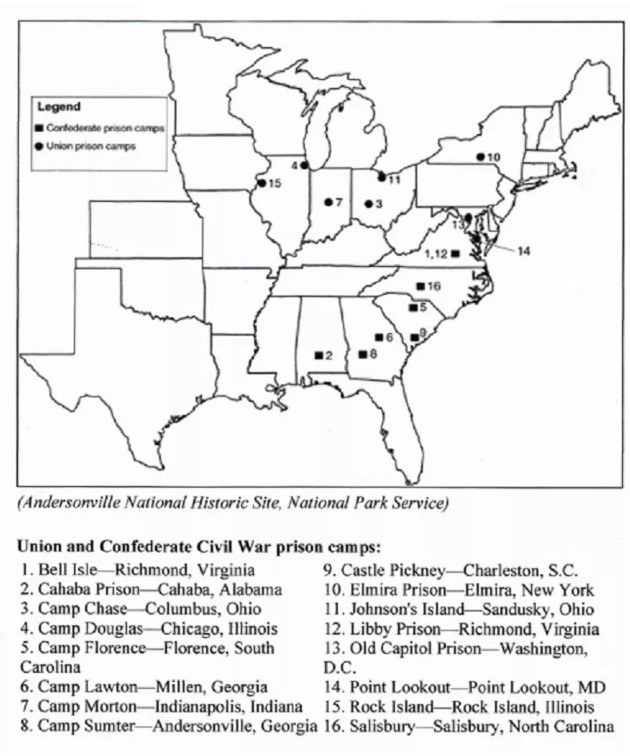

Among the deadliest sites for Southern prisoners were Chicago's Camp Douglas, New York's Elmira Prison, and Point Lookout Prison in Maryland. The deadliest locations for Northern prisoners included Georgia's Camp Sumter (better known as "Andersonville Prison"), North Carolina's Salisbury Prison, and the Florence Stockade.

Florence Stockade was constructed (by local slaves) on Jefferies Creek in Florence within walking distance of the Florence's rail lines.

As many as 18,000 Northern troops and a small number of sailors were imprisoned there. Florence was chosen as a site for the prison “because of its rail access and because the Pee Dee backcountry appeared secure from Northern invaders.”

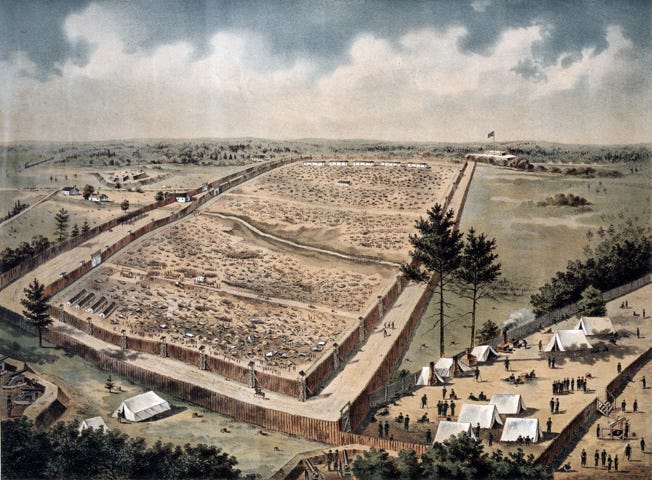

Modeled after Andersonville Prison, Florence Stockade was a “rectangular-shaped outdoor facility, protected by a palisades fence erected atop huge earthen walls.”

Prisoners began arriving before construction of the camp was complete and no housing existed. POWs were left to dig the sandy soil and build their own housing in “crude burrows covered with pine branches.” Conditions were horrible. Rations were severely limited and a winter ice storm left hundreds of dead in a single night.

Prisoner Ezra Ripple of the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry recorded his experience in the Florence Stockade in his memoirs:

“There was nothing left to do but dig a hole in the ground. As it would have to be roofed over with our gum blankets, we could only dig it as long and as wide as they would permit, and in that hole the four of us had to harbor for the winter. We dug it about three feet deep, but could not make it long enough to allow us straighten out our legs, or wide enough to permit us to lie in any other way than spoon fashion. Our shoulders and hip bones made holes in the ground into which they accurately fitted, and so closely were we packed together that when one turned we all had to turn. Lying all night in our cramped position with no covering, keeping life in each other by our joint contribution of animal heat only, we would come out of the hole in the morning unable to straighten up until the sun would come out to thaw us and limber our poor sore, stiff joints.”

Hearing stories about the Florence Stockade, local citizens became concerned. The public’s concern prompted the exchange of the most seriously ill and injured prisoners, and “large-scale transfers and exchanges emptied the prison in January of 1865, just five months after its construction.”

Yet even in the short time the Florence Stockage was in operation, 2,800 Federal troops had perished. They were buried nearby in mass graves in what became the Florence National Cemetery.

Near the mass grave markers is the grave of Florena Budwin, a Northern woman who disguised herself as a man to follow her husband into war — and eventually into the Florence Stockade. She wrote of the experience:

“This place gets colder ever day, and it does not help when your clothes are falling apart. The vermin are still a huge problem, as well as the hunger and insanity. To make things worst, some of the women of the town come stand on the embankments and mock us in their taffeta and silk. Typical Southern hospitality! I can not be too harsh though. One woman used to come by with a basket of food and throw it over the walls to us. The guards kept trying to stop her and finally banned her from ever coming back.”

Florena Budwin’s identity was discovered at the Florence Stockade and she worked there for a short time as a nurse until she sickened and died. She was “buried with full-military honors and became the first female service member interred in a National Cemetery.”

Florence Stockade is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and a local preservation group, Friends of the Stockade, and the City of Florence have developed a walking tour of the prison site — the Stockade Trail and Memorial Park.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“...our hearts were so full of joy that we could not act like sane persons, but would cry and laugh and hug each other, and do the most foolish things in our unutterable joy.”

—Florence Stockage prisoner Ezra Ripple of the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry on the day he was released from the Florence Stockage in February 1865

Hell Hole Swamp Moonshine article source:

“Moonshine Over Hell Hole Swamp.” Charleston Magazine, 20 Nov. 2015, https://charlestonmag.com/features/moonshine_over_hell_hole_swamp. Accessed 20 Apr. 2024.

Florence Stockade article sources:

“‘Comfortable Camps?’ Archeology of the Confederate Guard Camp at the Florence Stockade (Teaching with Historic Places) (U.S. National Park Service).” NPS.Gov Homepage (U.S. National Park Service), https://www.nps.gov/articles/-comfortable-camps-archeology-of-the-confederate-guard-camp-at-the-florence-stockade-teaching-with-historic-places.htm. Accessed 20 Apr. 2024.

“Florena Budwin | History of American Women.” History of American Women, 4 Sept. 2006, https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2006/09/florena-budwin.html. Accessed 20 Apr. 2024.

“South Carolina History Trail Regions.” History Trail of Northeastern South Carolina, http://www.schistorytrail.com/property.html?i=130. Accessed 20 Apr. 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!