#142: History of South Carolina in World War I + Pictorial History of Falls Park in Greenville

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, upcoming SC historical events, and other South Carolina recommendations.

Dear readers,

Welcome to SC History Newsletter #142!

I hope everyone had a wonderful Easter! I hope it was a day full of reflection, love, and hope for all.

On the history front: Did you know? This past weekend brought the 250th anniversary of Paul Revere’s Ride (April 18, 1775), as well as the Battle of Lexington & Concord (April 19, 1775). So exciting!

While my mind has been on the America250 and SC250, I began to think about South Carolina’s role in the World Wars as well. These musings led me to today’s topic on SC in World War I. I hope you enjoy.

Now, let’s learn some history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Support the SC History Newsletter by considering heritages teas (inspired by South Carolina and American history!) from our fantastic sponsor Oliver Pluff & Co. — click on their beautiful ad below! :)

➳ Housekeeping for new subscribers!

New friends! There are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and more! See our archive here!

Send me your comments or topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Have additional ideas or feedback? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Keep the conversation going and join over 100 other subscribers by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here!

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

Love the SC History Newsletter? Please click the button below to share with a friend!

➳ Featured SC History Event of the Week:

🗓️ Thursday, May 15th at 6:30 pm

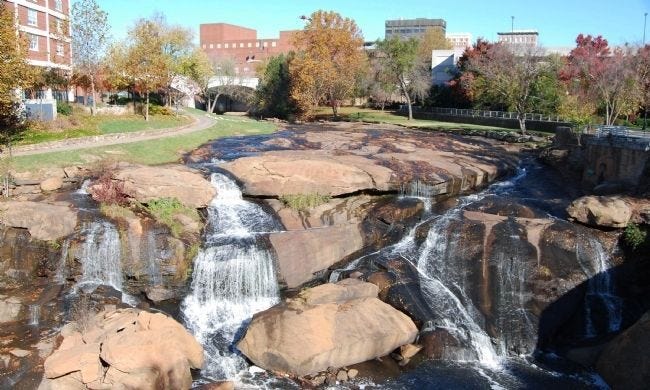

📝 “Pictorial History of Falls Park”

📍First Presbyterian Church | Greenville, SC

🎟️Free for Greenville Historical Society Members and First Presbyterian Members; $15 for non-members

💻 Website

From the event website:

MAY 15 | PICTORIAL HISTORY OF FALLS PARK

Speaker: John Nolan

Description: The Reedy Falls have played a central role in Greenville from its beginnings as a hunting ground for the Cherokee tribe through its textile era and into the present day. Take an enjoyable look at what the river looked like with hundreds of images spanning from 1821 to 2023 and what its evolving role was for through the years. You're sure to see views of the Reedy River and falls areas that you’ve never seen before.

➳ 🗓️ Paid subscribers get access to my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

➳ SC History Topic of the Week:

History of South Carolina in World War I

While America officially declared war on Germany in April 1917, South Carolina was already poised for the fight, having had a bizarre encounter with a German ship in Charleston Harbor a few months prior.

In February, 1917, a German freighter, SS Liebenfels, tried to block the Charleston Navy Yard channel. The ship’s “skeleton crew” failed in this operation and were all convicted and sent to prison.

The German freighter was seized by American forces in Charleston Harbor, and 6 other German vessels seized in U.S. ports would be refitted at the Charleston Navy Yard and christened with new American names.

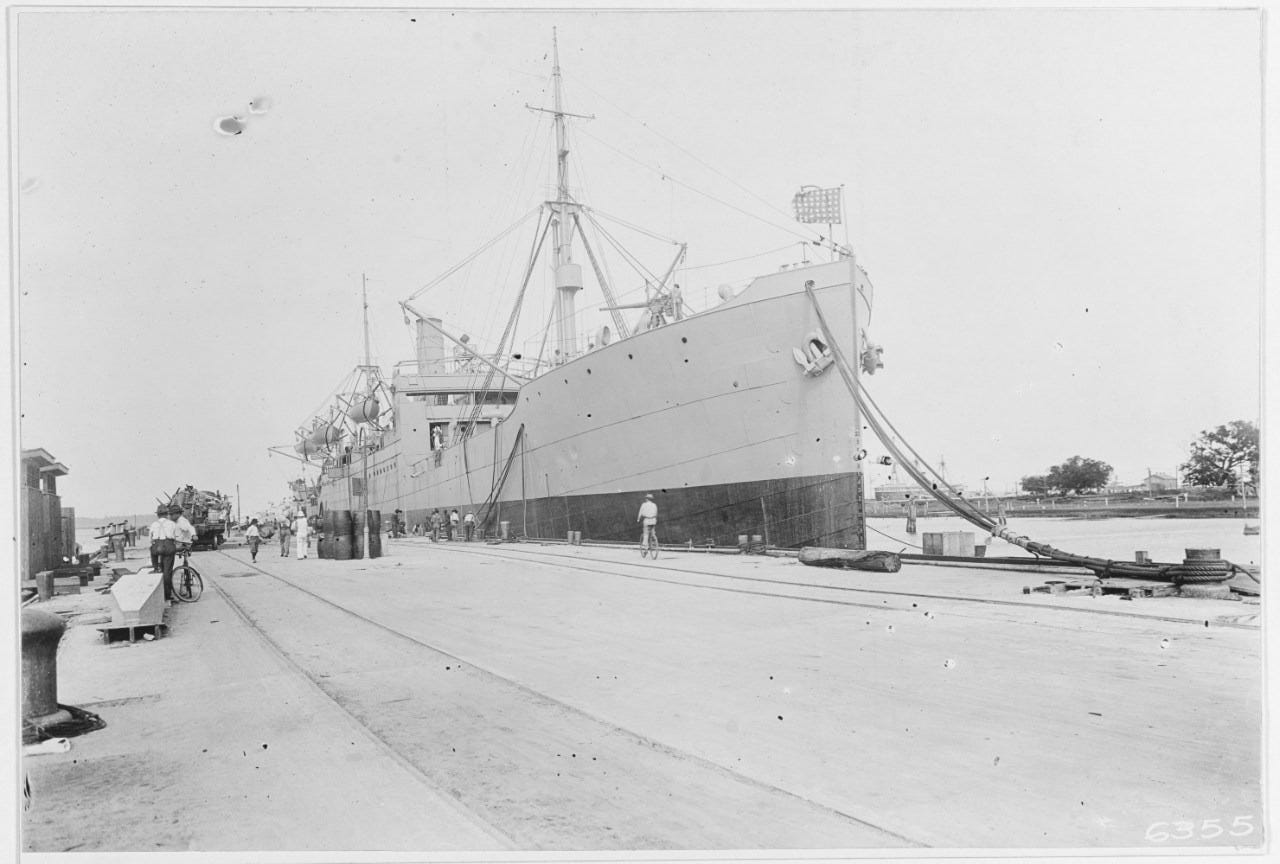

The SS Liebenfels ship was renamed the USS Houston and finished July 2, 1917 at the Charleston Navy Yard. See photo below!

Conversion of the SS Liebenfels to the USS Houston finished July 2, 1917 at the Charleston Navy Yard. (Image Source: NPS.gov) Renowned American artist Norman Rockwell was a young sailor stationed at the Charleston shipyard and Navy base during World War I — wow! While stationed there, Rockwell created his painting “Are We Downhearted?” It became a cover illustration for Life Magazine, Nov. 28, 1918.

The National Parks service describes war-time operations at the Charleston Navy Yard:

“Given the escalating demand for labor, employment figures started to rise at the Navy Yard even before American entry in the war. The Navy Yard, by 1919, would employ about 5,000 civilian employees, including African-Americans. Roughly one-fifth of this labor force were women working at the clothing factory, the only one operated by the US Navy. They produced millions of garments during the war, and by January 1919, the factory churned out 11,000 each day. Civilian laborers, among them women and African-Americans, used the war to demonstrate their patriotism and also their active citizenship through marching in Liberty Loan parades, fundraising for the Red Cross, staging receptions for returning veterans, and protesting poor service from a local cable car company.”

Inland, cities like Greenville, Spartanburg, and Columbia were eager to build army training centers in their communities “for both economic and patriotic reasons.”

The Governor of South Carolina in 1817 was Robert I. Manning, who embraced the war effort “with Patriotic zeal” and he was supportive of efforts for the state to join the fight.

However, there were some detractors. Former Governer Coleman Blease spoke out publicly against the war and tried to lobby the support of textile workers in particular. His efforts failed.

More than 65,000 South Carolinians served in the U.S. armed forces in WWI.

According to The Associated Press, a Newberry, SC resident named Robert Gilliam was so caught up “in war fever” that he enlisted at age 16, becoming one of the first American “doughboys” to land in France. Gilliam’s spirits ran high in advance of the Battle of Chateau Thiery, the first major action for many in U.S. Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing’s untested American Expeditionary Force. But the horrible weapons of modern war — bombs, rapid-fire machine guns, poisonous gas — took Gilliam out of the fight in short order. Blinded and paralyzed, his combat wounds were so severe he needed his attending nurse to pen a note home to his mother:

“My Dear Mrs. Gilliam,

Your son Robert asked me to write to you. At present he is unable to do this himself. As you must know by this time he was wounded July 18, 1918 – a serious wound of the frontal portion of his skull. He is conscious and does not suffer too much.”

Others kept the home fires burning and supported the war effort in other ways through “through liberty bond drives, home gardens, and meatless and wheatless days.”

On the role of women in South Carolina during the war, the South Carolina Encyclopedia writes:

“Through the Women’s Committee of the South Carolina State Council of Defense, many women made significant, but often unrecognized contributions. With the onset of war-time food shortages, the committee provided instructions on how to can and preserve foods and methods to grow “Liberty Gardens.” Women also entered the workforce as young men went to war. A few joined the army nurse corps. Patriotism cut across racial boundaries in broad support of bond drives and the Red Cross.”

Women were recruited by the government to fulfill many roles left behind when the men of communities enlisted in the war effort. Women stepped into wartime roles such as “manufacturing everything from textiles to tanks and airplanes… and they also found work as secretaries, nurses and in the world of academics, with some women going into higher education to earn Ph.D. degrees.”

WWI revitalized South Carolina’s main industries of agriculture & textiles.

Total farm incomes in South Carolina rose from an average of $121 million in 1916 to $446 million during the war.

The value of textile production doubled between 1916 and 1918, from $168 million to $326 million.

New military posts and installations improved the economies of South Carolina communities.

Camp Sevier in Greenville, Camp Jackson in Columbia, and the Charleston Navy Yard sparked large population increases, from the arrival of both armed forces personnel and civilian employees.

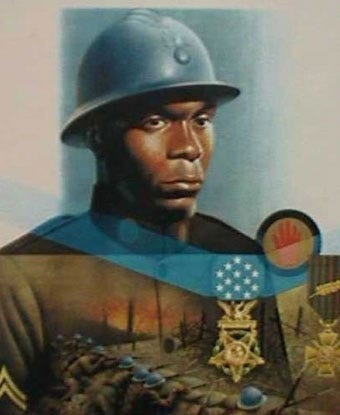

The 371st Infantry Regiment, which trained at Camp Jackson in Columbia and made up of black draftees from the Carolinas, served with distinction on the French front.

Notable among the 371st Infantry Regiment was Cpl. Freddie Stowers, of Sandy Springs near Anderson, who would go down in history as the first black soldier awarded the Medal of Honor for valor in the war. The recognition didn’t come until 1991, more than 70 years later.

On April 24, 1991, President George H.W. Bush posthumously awarded Corporal Freddie Stowers the Medal of Honor at a White House ceremony. Stowers’s two sisters accepted the award on the family’s behalf.

Many of the positive changes brought on by WWI in South Carolina would not last forever. When Germany surrendered in November 19818, military and naval bases in South Carolina “quickly demobilized, with most closing by the early 1920s.”

Only the Charleston Navy Yard and the Parris Island Marine installations remained active, but at “reduced levels.”

The boom of the war quickly reversed into an “economic tailspin” throughout the state where war-time food and cotton surpluses after 1918 saw farm prices drop dramatically.

Cotton prices fell from a war-time high of 40¢ a pound to less than half that by the early 1920s.

Textile mills, which were the central to the state’s economy, slashed war-time wages, which led to massive textile worker strikes.

Sadly, race relations were arguably worse after WWI in South Carolina.

Many returning African American servicemen who had served in the war were sadly not welcomed home with gratitude, but with race riots across the United States, including one in Charleston in 1919.

With Jim Crow discrimination on the rise, opportunities for African Americans returned to their pre-war levels. This led to a “mass exodus” African American to northern cities in the upcoming two decades.

In total, America’s involvement in the war lasted about 20 months but only about a quarter of that included periods of battlefield fighting. In the end, roughly 1,100 South Carolinians died during the war, mostly from sickness and disease.

8 South Carolinians would receive the Medal of Honor for their bravery in combat in WWI. Their names are listed below, and thankfully, I was able to find their photos (except 2) below as well from the Congressional Medal of Honor Society website. May we honor these men today for their bravery and sacrifice.

James. C. Dozier - died in Montbrehain, France

Gary E. Foster - died in Montbrehain, France

Thomas L. Hall - died in Montbrehain, France

James D. Heriot - died in Vaux-Andigny, France

Richmond H. Hilton - died in Brancourt, France

Freddie Stowers - died in Champagne Marne Sector, France (as mentioned above, he was the first black soldier ever awarded the Medal of Honor for valor in the war)

Daniel A. Sullivan - died in Western France

John C. Willepigue - died in Vaux-Andigny, France

If you voted just “OK” on the newsletter today, I want to hear from you! Reply to this email and send me your feedback. :)

➳ Sources — History of South Carolina in World War I

“Camp Jackson.” Veteran Voices, https://veteran-voices.com/world-war-i-training-camps/camp-jackson/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

“Camp Sevier in Greenville Played Critical Role in WWI.” Greenville News, 18 Jan. 2018, https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/entertainment/2018/01/18/camp-sevier-greenville-played-critical-role-s-100th-anniversary-commemorated-remember-old-hickory-pr/1043588001/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

“Charleston and World War I.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/charleston-wwi.htm. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

“Freddie Stowers.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/freddie-stowers.htm. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

“Medal of Honor Recipients.” Congressional Medal of Honor Society, https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/page/1?action_year[start]=1917&action_year[end]=1921&state_accredited_to[]=43. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

“Norman Rockwell and the Charleston Navy Yard.” Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum, https://www.patriotspoint.org/news/norman-rockwell-charleston-navy-yard. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

“Symposium Examines Women’s Roles during World War I.” South Carolina Public Radio, 9 Apr. 2019, https://www.southcarolinapublicradio.org/sc-news/2019-04-09/symposium-examines-womens-roles-during-world-war-i. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

“The Relic Room Joins All South Carolina in Honoring the 371st Regiment.” South Carolina in Vietnam, https://scinvietnam.com/the-relic-room-joins-all-south-carolina-in-honoring-the-371st-regiment/. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

“World War I.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/world-war-i/#:~:text=More%20than%2065%2C000%20South%20Carolinians,and%20meatless%20and%20wheatless%20days. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.

World War I Posters Collection. South Carolina State Library, https://dc.statelibrary.sc.gov/items/d44bb16e-68d6-4065-9e1b-6c4f80113365. Accessed 19 Apr. 2025.