#72: Robert Smalls, Kudzu, and a lecture on The Revolutionary War in Horry County

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #72 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

rlavelle54

bjohnson6311

mimijones66

warthennell

baggettmarya

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Refer your friends to SC History Newsletter and win a “Best of South Carolina” basket (value $100)!

Hi everyone! I am SO grateful and excited that there are now 470 subscribers for the SC History Newsletter. Y’all are amazing!! I have a goal for us to get to 1,000 subscribers by May 20th. Can you help me achieve my goal? And let’s make it fun by making it a contest!

HOW TO ENTER: By using the button below, you can share a unique link to the SC History Newsletter with your friends. Each time one of your friends signs up for the newsletter from your unique link, I can see on my dashboard!

WINNER: The person who refers the most people who sign up for the SC History newsletter will win the “Best of South Carolina” basket on May 20th! I will keep everyone posted on the “standings” as they come in.

THE PRIZE: The basket of goodies (valued at $100) will include iconic sweet & savory South-Carolina made goods — and a few other surprises as well!

Start sharing today! Thank you so much!

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

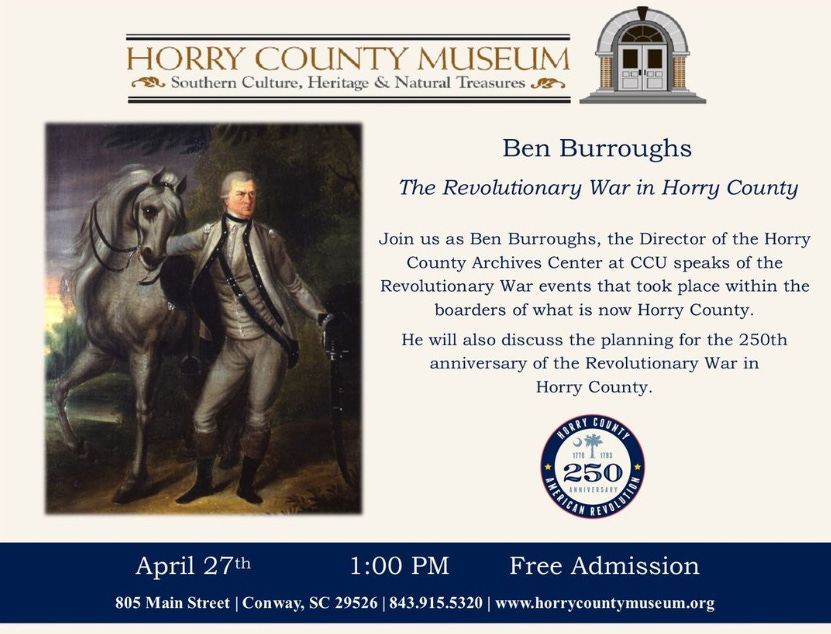

Saturday, April 27th at 1:00 pm | “Ben Burroughs: The Revolutionary War in Horry County” | Horry County Museum | Conway, SC | FREE Admission

“Join Ben Burroughs, the Director of the Horry County Archives Center at Coastal Carolina University, on Saturday, April 27, as he speaks on some of the Revolutionary War events that took place within the borders of what is now Horry County. He will also discuss the planning for the 250th anniversary of the Revolutionary War in the County.

After the program, there will be a 5-minute break and then the Spring Business Meeting for the Horry County Historical Society membership will take place. Members of the HCHS are encouraged to stay and guests are welcome.

Ben is the director of the Horry County Archives Center, established at Coastal Carolina University by the Horry County Higher Education Commission in 2006. The center focuses on researching the history of Horry County and surrounding counties, including the history of Coastal Carolina University. The center works with local history-minded groups to find significant historical material, preserve it and make it accessible to the public via digitization.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

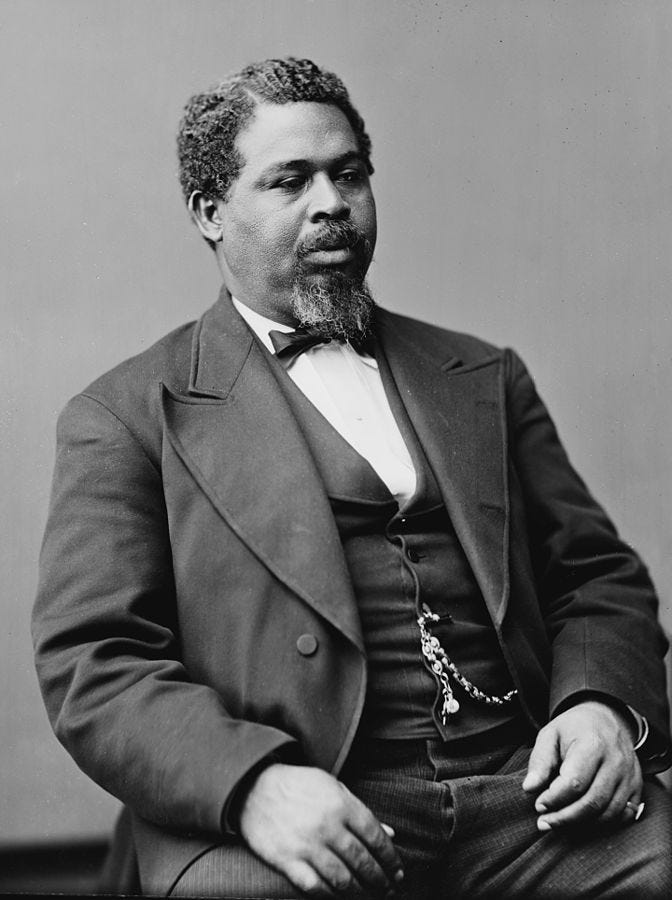

Do you know about Robert Smalls’ daring escape from slavery on the CSS Planter ship and that he would become one of the founders of the Republican Party of South Carolina?

Robert Smalls has one of the most remarkable stories of the Civil War & Reconstruction period. A number of y’all have requested that I share his story which I hope to do justice to in today’s newsletter.

Smalls was born in Beaufort on April 5, 1839. He was the son of an enslaved woman named Lydia Polite. His father is unknown, but some speculate his father may have been Henry McKee, Lydia’s master.

Lydia gave birth to Robert at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort, SC in a cabin behind her master, Henry McKee’s house. Keep this in mind for an amazing ending to Smalls’ story later on…

In 1851, his master Henry McKee “hired out” then 12-yr-old Robert Smalls as a laborer in Charleston. The young Smalls worked as a “waiter, a lamplighter, a stevedore, and eventually a ship rigger and sailor on coastal vessels.”

On December 24, 1856, he married an enslaved woman 14 years older than him named Hannah Jones. The couple had 3 children. When Hannah died in 1883, Smalls married Annie Elizabeth Wigg in 1890. They had 1 child.

Smalls was determined to buy freedom for himself and his family. Smalls “was allowed to keep a dollar a month of his wages.” He saved every penny he could and used the proceeds towards a “$100 down payment on the freedom of his family.”

Interestingly, Smalls and his family lived separately from their masters, but since they were “hired out” in Charleston, they “sent their masters most of their income.”

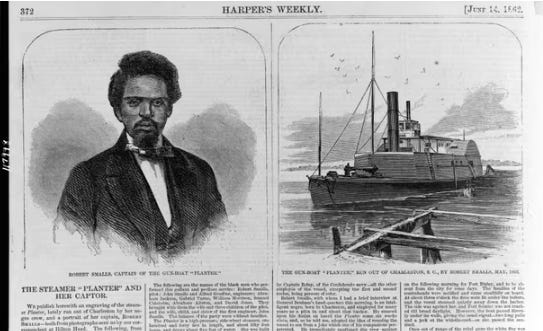

At the start of the Civil War, Smalls was employed as a pilot on the Confederate armed courier vessel, the 147-ft CSS Planter.

In his work on the Planter, Smalls learned quickly about the routines of the white crew — when they boarded the ship, when they left the ship empty — as well as the nautical signals and codes the captains used when passing certain Confederate checkpoints in the harbor. He was also aware of the Union blockade of ships in Charleston harbor. He began to make a plan for escape.

Around 3:00 am on the morning May 13, 1862, when the CSS Planter was docked and deserted, Smalls donned the “top hat and long coat” of the boat’s Confederate captain. With the help of the ship’s enslaved crew, Smalls and his team “fired up the ship’s boilers” and sailed to a nearby wharf to pick up their family members. From there, the 15 enslaved men, women, and children began their daring escape. Smalls hoisted the Confederate and South Carolina flags and ordered the women and children sent below. In his disguise, Smalls calmly sailed past Fort Johnson and Fort Sumter — giving the proper signals at each stop. At Fort Sumter, the signal was “two long and one short blasts of the whistle.” In the pre-dawn darkness, and in his disguise, no one would have been able to distinguish Smalls from the white captain of the ship.

After making it through the Confederate checkpoints, Smalls “opened the throttle” of the Planter towards the ships of the Union Blockade. He took down the Confederate flags and hoisted a white bedsheet as a makeshift flag of surrender. Onboard the clipper ship USS Onward, the Union officers noticed the Planter hurrying out of the channel and sent their crew to battle stations, until they noticed the makeshift white flag. Smalls pulled the Planter alongside and hailed the captain of the Onward: “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!” The men and women on the Planter were free!

For his daring act of commandeering the Planter and using it for the escape mission, Smalls became famous, and the “information he provided on Confederate defenses was valuable in planning Union operations. Congress voted prize money to the crew for their deed, with Smalls receiving $1,500.”

As Smalls was a pilot with great knowledge of the South Carolina waterways, his services were “in high demand” with the Union army.

On December 1, 1863, he was piloting the Planter once again, now a Union vessel, near Secessionville, SC when severe enemy fire caused the white captain of the ship to abandon his post. Smalls steered the ship to safety. For his bravery, he was awarded “an army contract as captain of the Planter.

Smalls was “the first black man to command a ship in U.S. service and remained captain of the Planter until it was sold in 1866.”

By his own count, “Smalls was involved in 17 military engagements” during the Civil War.

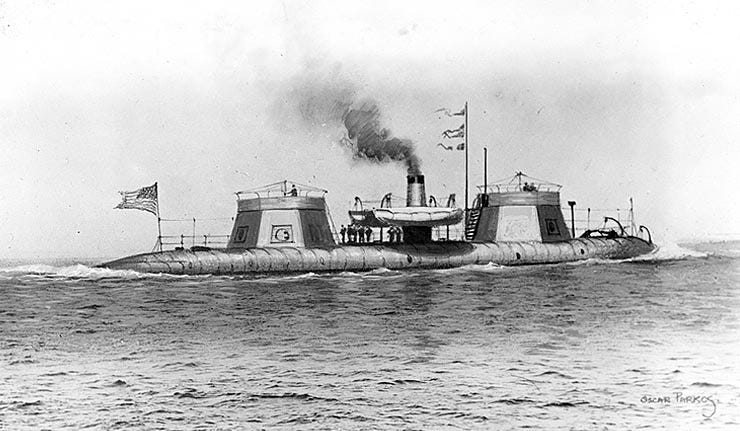

He also served at one point in time as the pilot of the ironclad ship the USS Keokuk.

After the war — in an amazing “full circle” turn of events — Robert Smalls returned, as a free man, to his native Beaufort, SC and was able to purchase the house of his former master, Henry McKee.

Smalls’ wartime accomplishments and feats of bravery made him a force in the area of the Sea Islands, which had an overwhelmingly black population.

In 1867 Smalls was one of the founders of the Republican Party in South Carolina, an organization to which he remained loyal all his life.

Along with his political career, Smalls also opened a store and a school for black children in Beaufort. He also published a newspaper, the Beaufort Southern Standard, starting in 1872. Smalls’s local contributions and his ability to speak the Sea Island Gullah dialect enhanced his local popularity and opened doors in South Carolina politics.

In 1868 he was a delegate to the state constitutional convention and won election to the SC House of Representatives, where he represented Beaufort County until 1870.

In 1870, Beaufort voters sent Smalls to the state Senate, and in 1873 he was promoted to major general in the militia.

In the Senate, Smalls was made chairman of the printing committee, and in 1877 he was tried and convicted of accepting a $5,000 bribe and was sentenced to 3 years, but was eventually pardoned. Even Smalls’s enemies at the time “said that the case against him was not strong, and it was likely part of the campaign to remove African Americans from public office.”

Summarizing the next part of his political career, the SC Encyclopedia writes:

“In 1874 Smalls was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He was reelected to the following Congress and served intermittently until 1886. With the return of Democratic rule in South Carolina after 1876, Smalls had increasing difficulty winning reelection. He lost to George D. Tillman in 1878 and 1880 but successfully contested the results of the latter election and took Tillman’s seat in July 1882. Two years later Smalls failed to secure renomination, losing to Edmund W. M. Mackey, who died soon after taking office. Smalls was elected to fill the vacancy and returned to Washington in March 1884, but he lost a bid for another term in 1886. While in Congress, Smalls earned a reputation as an effective speaker. He secured appropriations for harbor improvements at Port Royal and was a vocal opponent of the removal of federal troops from the South.”

Smalls fought throughout his political career “to secure full citizenship and equality for Black Americans.”

He made this famous statement to the South Carolina legislature in 1895:

“My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be equal of any people anywhere…All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

All in, Robert Smalls served 5 terms in the U.S. House representing his South Carolina district that was described as a “black paradise” because of its opportunities for freed men.

When Robert Smalls returned full-time to Beaufort, he successfully lobbied his former congressional colleagues for a veteran’s pension and more compensation for his service on the Planter.

His last major political role was serving as one of 6 black members of the 1895 SC constitutional convention, where he “unsuccessfully opposed efforts to disenfranchise African Americans.”

In 1889 President Benjamin Harrison appointed Smalls as collector of customs for the port of Beaufort, an office he held (except during President Grover Cleveland’s second term) until June 1913, when he was forced out by South Carolina’s senators.

Smalls died on February 22, 1915, at his home in Beaufort. He was buried in Tabernacle Baptist Churchyard.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you know that goats may be one of the few ways to stop the spread of South Carolina’s dreaded kudzu vine?

Anyone who lives in South Carolina will likely have had at least one moment of “wow” at the extent to which the kudzu vine has taken over large swaths of forest all over the state. It’s scary!

Kudzu is known as “mile-a-minute” and “the vine that ate the South.”

Per the Nature Conservancy, kudzu is a “creeping, climbing perennial vine terrorizes native plants all over the southeastern United States and is making its way into the Midwest, Northeast and even Oregon.”

Kudzu is native of Japan and southeast China.

It was first introduced to the United States with the best of intentions at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876 where “it was touted as a great ornamental plant for its sweet-smelling blooms and sturdy vines.”

Then, in the 1930s through the 1950s, the Soil Conservation Service promoted kudzu as a “great tool for soil erosion control” and was planted in abundance throughout the south:

“85 million kudzu plants were given to southern landowners by the Soil Erosion Service for land revitalization and to reduce soil erosion and add nitrogen to the soil. The Civilian Conservation Corps also planted kudzu throughout the South. The government offered up to $8 per acre as an incentive for farmers to plant their land in kudzu. About 3 million acres of kudzu had been planted on farms by 1946. Ironically, due to difficulties in establishment, many of these initial plantings did not survive.”

In the 1940s, numerous “kudzu clubs were formed throughout the South. Kudzu festivals were held, and kudzu queens were crowned.”

In 1943, Channing Cope, a journalist and radio show host in Covington, Georgia, founded the Kudzu Club of America, which eventually had a membership of about 20,000 individuals. He became known as the “Father of Kudzu.”

By the early 1950s, kudzu had largely become a nuisance. It had spread rapidly throughout the South because of the long growing season, warm climate, plentiful rainfall, and lack of disease and insect enemies. Abandonment of farmland during this time contributed to the uncontrolled spread of kudzu.

In 1953, the United States Department of Agriculture removed kudzu from the list of cover plants permissible under the Agricultural Conservation Program.

In 1962, the Soil Conservation Service limited its recommendation of kudzu to areas far removed from developed areas. Finally in 1970, the USDA listed kudzu as a common weed in the South. Congress voted in 1997 to place kudzu on the Federal Noxious Weed list, where it remained for a few years. While no longer on the Federal Noxious Weed list, kudzu is currently listed as a noxious weed in 13 states.

Once established, the kudzu vines can grow at a rate of 1 foot per day, with mature vines as long as 100 feet.

Kudzu stifles native plants and “outcompetes” everything from native grasses to fully mature trees by stifling out the sunlight they need to photosynthesize.

If not brought under control, the loss of habitat loss from the kudzu plant could lead to species extinctions and “loss of biodiversity.”

In terms of getting rid of kudzu, there is hope! It has been discovered that goats eat kudzu vines, especially in hard-to-reach areas, which allows property owners to reclaim their yard and take the next steps for destroying the kudzu completely, by digging up the vine’s roots. Additionally, as they eat the kudzu and brush, “goats replenish nutrients to the ground while the goat’s saliva renders the kudzu seeds infertile.”

Recently, where I live in Greenville, 3 dozen goats from the Roxbury Goat Farm were hired out for a month to remove invasive species along the Reedy River and they made amazing progress ridding the park of these pesky plants. And even more charming, the goat herd is named “The Dairy Queens”!

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“The accession if this contraband pilot to the Union cause is most important, as, besides his intimate and minute knowledge of every inlet and river on the South Carolina and Georgia coasts he has given full particulars of the manner in which the rebel vessels have run the blockage, and those which are not preparing to do so. This information cannot fail to throw many prized into the hands of the fleet. The vessel and funs he brought to the blockading officers are work about $35,000.”

—Excerpt from The Boston Daily Advertiser; May 20, 1862; Boston, Massachusetts

Robert Smalls article sources:

Gates Jr, Henry Louis Gates. “Which Slave Sailed Himself to Freedom?” The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross, 13 Jan. 2013, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/which-slave-sailed-himself-to-freedom/. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

Eatmon, Myisha. “Robert Smalls.” University of South Carolina, https://sc.edu/about/our_history/university_history/presidential_commission/commission_reports/final_report/appendices/appendix-3/smalls-robert/index.php#:~:text=While%20serving%20as%20a%20Representative,its%20use%20of%20The%20Citadel.&text=Smalls%20also%20fought%20to%20secure%20full%20citizenship%20and%20equality%20for%20Black%20Americans. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

Miller, Edward. “Robert Smalls.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/smalls-robert/#:~:text=He%20was%20the%20first%20black,house%20of%20his%20former%20master. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

“Robert Smalls.” Govinfo.org, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CDOC-108hdoc224/pdf/GPO-CDOC-108hdoc224-2-2-16.pdf. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

“Robert Smalls.” NPS.Gov Homepage (U.S. National Park Service), https://www.nps.gov/people/robert-smalls.htm. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

“Robert Smalls and the Planter.” American Battlefield Trust, 24 Sept. 2020, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/robert-smalls-and-planter. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

“The Incredible Life of Robert Smalls.” African American Charleston, https://www.africanamericancharleston.com/articles/the-incredible-life-of-robert-smalls/. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

Kudzu article sources:

“History and Use of Kudzu in the Southeastern United States - Alabama Cooperative Extension System.” Alabama Cooperative Extension System, https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/forestry-wildlife/the-history-and-use-of-kudzu-in-the-southeastern-united-states/. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

“Kudzu: The Invasive Vine That Ate the South | TNC.” The Nature Conservancy, https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/united-states/indiana/stories-in-indiana/kudzu-invasive-species/. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

Williams, Rashad. “‘Goatscaping’ Helps Ease Spread of Invasive Plant.” WYFF, 15 Sept. 2022, https://www.wyff4.com/article/goatscaping-invasive-plant-kudzu-south-carolina/41234031. Accessed 22 Apr. 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!

I love this one. He’s pretty well known in this area. I doubt you have time for many books but I did read this one: Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls' ...

Amazon.com

https://www.amazon.com › Be-Free-Die-Amazing-Slave...

be free or die from www.amazon.com

This is an amazing story about Robert Smalls' heroic feats during the Civil War (and after) and his astounding courage and determination. Author Cate Lineberry ...

The boat escape was quite harrowing.