#151: Harriet Tubman’s Forgotten Raid on South Carolina Soil + Carolina Day on June 28th

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, upcoming SC historical events, and other South Carolina recommendations.

Dear readers,

I was thrilled to head to Charleston on Friday for a “solo culture day” and to see a few sites I have not visited yet and have been very curious about — namely, the beautiful Gibbes Museum and the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon.

My visit to the Gibbes Museum inspired my essay today on Harriet Tubman’s Combahee River Raid, a moment in history that is utterly fascinating to me. I hope you enjoy.

Meanwhile, I also spent a whole hour just in the Gibbes Museum gallery dedicated to their historic miniature portrait collection — a true South Carolina history treasure. The collection showcases the images of many prominent South Carolina family members and is utterly amazing. Every miniature seemed like it was alive with history — the hairstyles, the fashions, the tiny details. The portraits were stunning. Be sure to visit sometime!

Then, I had lunch at the locally-loved restaurant, Millers All Day. I had their banana bread topped with Nutella cream cheese, cornmeal pancakes, home fries, and a biscuit (don’t worry, I hadn’t eaten breakfast and there were leftovers!).

After lunch, I proceeded to the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon which I was so happy to discover, as a DAR member myself, has been the meeting place of the Rebecca Motte Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution for over 100 years — and it sounds like that chapter has had a lot to do with the upkeep and maintenance of this historic building.

On the 2nd floor of the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon is the ballroom where George Washington was wined & dined on his only ever visit to South Carolina. I did a few little dance steps on the historic wood floor to say I’ve danced on the same floor as Washington — yippee! Then I went down into the bowels of the building for the dungeon tour, which was chilling. It was amazing to imagine all the people who were once locked there behind bars, including pirates!

I’m thankful for the rich history of South Carolina and hope you enjoy today’s newsletter.

Sincerely,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Support the SC History Newsletter by considering heritages teas (inspired by South Carolina and American history!) from our fantastic sponsor Oliver Pluff & Co. — click on their beautiful ad below! :)

➳ Housekeeping for new subscribers!

New friends! There are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and more! See our archive here!

Send me your comments or topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Have additional ideas or feedback? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Keep the conversation going and join over 100 other subscribers by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here!

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

Love the SC History Newsletter? Please click the button below to share with a friend!

➳ Featured Upcoming SC History Events

📜 Fight for Freedom: A Carolina Day Commemoration

🗓️ Saturday, June 28th, 2025 - All Day

📝 Fort Moultrie

📍Charleston, SC

💻 Website

From the event website:

“What is Carolina Day?

Carolina Day is the annual commemoration of the Battle of Sullivan's Island that occurred on June 28, 1776. Fort Moultrie hosts Carolina Day events annually on the Saturday closest to June 28. During this weekend, the park hosts living historians, historic weapons demonstrations, ranger programs, and other activities.

Below is a listing of Carolina Day activities and America 250 commemorative events.

Saturday, June 28 is a fee-free day. Regular site fees resume on Sunday, June 29. This year marks the 249th anniversary of the Battle of Sullivan's Island. Living historians in period clothing will portray both Patriot and British soldiers and civilians to help visitors understand and learn about life in 1776.

Event Schedule:

Flag Raising Program 10:00 a.m., inside Fort Moultrie

Join a ranger and living historians to help raise the Moultrie Flag. Learn about the importance of the Battle of Sullivan's Island, what the battle between the fort and the navy looked like and the history behind the flag itself.

History Talk 10:30 a.m., behind Fort Moultrie

10:30 a.m.: Learn more about the forming of the patriot force that defended Fort Moultrie, the 2nd South Carolina Regiment.

History Talks 12:00 p.m., 1:00 p.m., 1:30 p.m. inside Visitor Center Theater

12:00 p.m.: Join a representative of the Catawba Nation and learn the history from first contact through present day.

1:00 p.m.: Join our living historians for a history talk about the South Carolina State Navy!

1:30 p.m.: Discover more about the British history here at Sullivan's Island with the 33rd Regiment of Foot.

Historic Weapons Demonstration 11:00 a.m., 11:30 a.m, 2:30 p.m, 3:00 p.m behind Fort Moultrie

Join living historians to learn about muskets, cannons and mortars. Experience what it would have been like when they were fired!

11:00 a.m. and 2:30 p.m.: Musket Demonstrations

11:30 a.m. and 3:00 p.m.: Artillery Demonstrations

Living Battle Demonstration 2:00 p.m., behind Fort Moultrie

Join rangers and living historians for a program showcasing Sergeant Jasper and his heroic actions as he rescues the Moultrie flag under gunshots and cannon fire!

Flag Lowering Program 4:30 p.m., inside Fort Moultrie

Join a ranger and living historians to help fold the Moultrie Flag. Learn about the importance of the Battle of Sullivan's Island, and how the fight for freedom continues to echo through time.

Guest Speaker 6:00 p.m., behind Fort Moultrie

Join us as we host historian and local author Norm Rickeman for a deep dive into the Battle of Sullivan's Island, and why he considers it "...the biggest upset victory in America's military history.

All Day Events 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m

History Row and Interactive Children's Activities

Ranger stations provide interactive activities for visitors of all ages, including:

learn how to build a palmetto log fort

make a keepsake musket cartridge

design a regimental flag

play colonial games

sift for artifacts with the park archaeologist.

Book Signing

Meet local author Norm Rickeman, who wrote THE book on Colonel Moultrie and the victory at the Battle of Sullivan's Island. Books will be available for purchase.

Cricket Demonstration

Join a historian to learn (and play!) the most popular game in colonial America.

Indigo Dyeing Demonstration

Join a Park Ranger to experience the magical look of indigo dyeing, and learn about the enslaved labor used to get the dye from the plant. Did you know this is the same dye that we use in blue jeans today?

Knot Tying Demonstration

Join the Royal Navy Bully Boys for an interactive demonstration on how sailors would have tied knots.”

➳ 🗓️ Paid subscribers get access to my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

➳ Freedom by Moonlight: Harriet Tubman and the Combahee River Raid, 162 Years Later

This past June 1st marked 162 years since Harriet Tubman’s Combahee River Raid in the Lowcountry of South Carolina. This was the largest slave liberation operation in American history.

I was lucky enough to go to Charleston last week to The Gibbes Museum for the first time. It was a wonderful afternoon. Their exhibition on Harriet Tubman’s Combahee River Raid was a big highlight and I highly recommend!

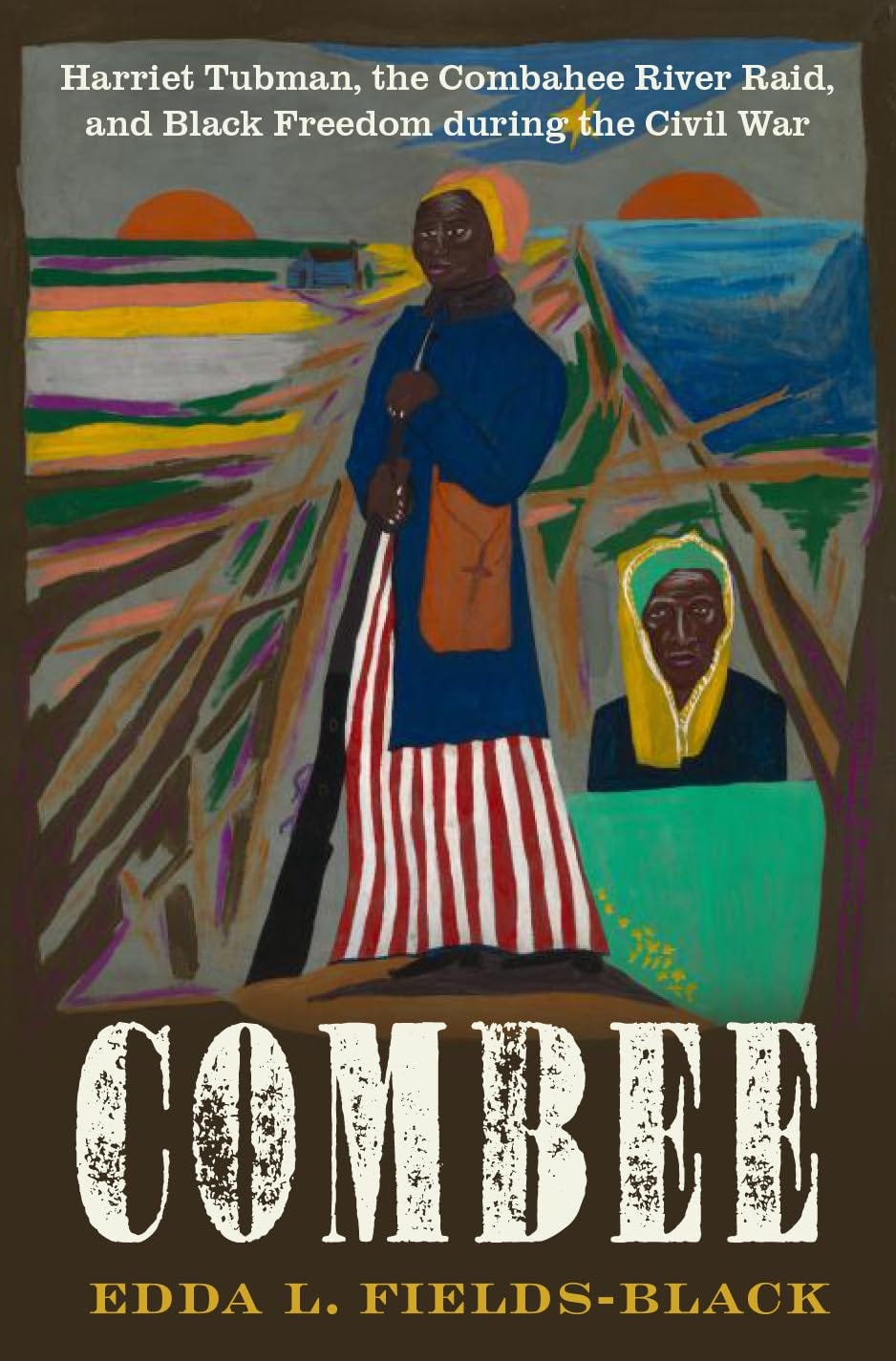

The Harriet Tubman exhibition is centered the fascinating research within the 2025 Pulitzer Prize-winning book that I have featured in the newsletter and I’m in the process of reading myself, Combee: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom During the Civil War by Edda Fields-Black.

Here is the exhibition description:

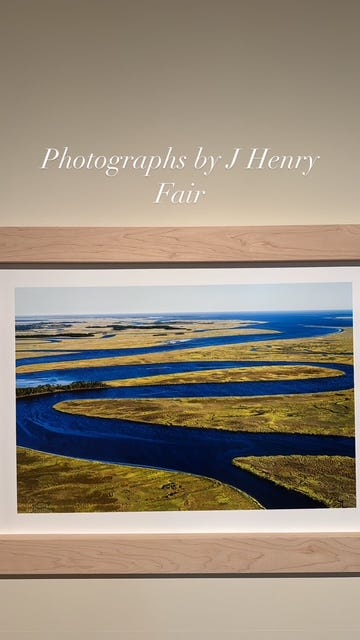

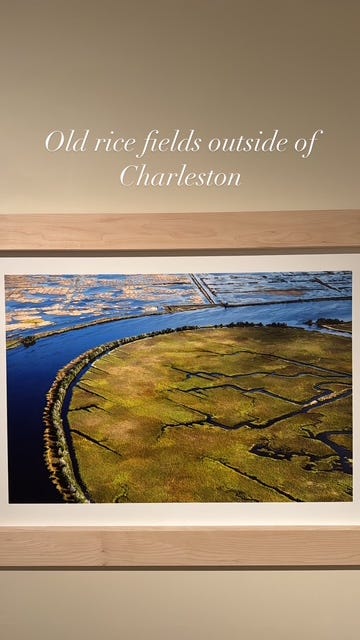

This exhibition is inspired by the untold story of the Combahee River Raid from the perspective of Harriet Tubman and the enslaved people she helped to free that is revealed for the first time through groundbreaking research by Carnegie Mellon University historian, Edda Fields-Black, Ph.D., in her recent book COMBEE: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom during the Civil War. Working in collaboration with J Henry Fair, renowned environmental photographer, and guest curator, Vanessa Thaxton-Ward, Ph.D., Director of the Hampton University Museum, the exhibition carefully recreates the full journey of these brave soldiers and freedom seekers on that fateful moonlit night.

On June 2, 1863, Harriet Tubman led the largest and most successful slave rebellion in the United States when her group of spies, scouts, and pilots piloted Colonel James Montgomery, the Second South Carolina Volunteers (300 Black soldiers), and one battery of the Third Rhode Island Artillery up the lower Combahee. African Americans working in the rice fields on seven rice plantations along the Combahee heard the uninterrupted steam whistles of the two US Army gunboats and ran to freedom. 756 enslaved people liberated themselves in six hours, more than ten times the number of enslaved people Tubman rescued on the Underground Railroad. The morning after the raid, 150 men who liberated themselves in the Raid joined the Second South Carolina Volunteers and fought for the freedom of others through the end of the Civil War.

Visitors to the exhibition will explore this dramatic event through Fair’s dynamic contemporary and environmentally sensitive photographs and video works, as well as contemporary and historic art objects, and material culture. Some of the artists included in the show include Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, William H. Johnson, and Stephen Towns. The exhibition sheds new light on the history of Tubman, the environmental challenges faced by enslaved laborers as they sought a path to freedom, and the significance of the Lowcountry’s historic rice fields on modern-day coastal wetlands.

Now let’s dive deeper into the history of Harriet Tubman’s Combahee River Raid.

Before 1863, Harriet Tubman had already gained fame as one of the leaders of the Underground railroad, a secret network of routes and safehouses used by enslaved workers in the United States to escape to free states and to Canada.

Tubman was born into slavery in her home state of Maryland. Her original name was Araminta Ross. She was called “Minty” for short. She and her family were owned by the Brodess family, who owned a large plantation near the Blackwater River in Dorchester County, Maryland.

As a child, Tubman was beaten and whipped by her enslavers. At one point, she was struck in the head by an overseer — an injury that caused dizziness, pain, and hypersomnia (excessive sleeping) throughout her life.

In fact, Tubman had vivid “dreams and premonitions” during this period of her life, which she believed were messages from God. Raised Methodist, Tubman was highly devout, and these visions increased her faith in her mission to be free and to free others.

In 1844, she married a freeman named John Tubman and changed her name to Harriet (after her mother) and adopted her husband’s last name. Although they were married, Harriet remained enslaved for another 5 years until she was able to plan her escape when “her enslaver died and she was to be sold.” She fled to Philadelphia.

Determined to help her friends and family escape from bondage, Tubman spent the next 10 years making 13 recue trips into Maryland.

In this period, she recued 70 slaves, including her brothers, Henry, Ben, and Robert, their wives and some of their children.

She also provided instructions that helped an additional 50-60 slaves escape to freedom.

Highly intelligent and strategic, Tubman used every tool she had for her missions:

“Tubman successfully used the skills she had learned while working on the wharves, fields and woods, observing the stars and natural environment and learning about the secret communication networks of free and enslaved African Americans to affect her escapes. She later claimed she never lost a passenger. The famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison called her "Moses," and the name stuck.”

She was, indeed, a “Moses” of her people.

Over the years, Tubman strengthened her brilliant skills in stealth communication and tactics. Tubman would often dress in disguise to divert attention. She would plan escape missions on Saturdays because newspapers wouldn’t publish missing slave advertisements until Monday morning — and this would allow more time for escape. She and her informants would use spirituals such as “Go Down Moses” as coded messages, which would warn fellow travelers of danger. She is famous for having traveled by night, guided by the North Star.

As she led escapees across the borders to freedom, she would call out, "Glory to God and Jesus, too. One more soul is safe!"

In a dictated letter to a friend, she said, "God set the North Star in the heavens; He gave me the strength in my limbs; He meant I should be free."

The Civil War broke out in 1861.

Harriet Tubman had a vision that the Civil War would lead to the abolition of slavery, and in January 1862, she volunteered to support the Union cause and began assisting refugee slaves in camps in Port Royal, SC.

In January 1863, President Abraham Lincoln released his Emancipation Proclamation, which further ignited the abolitionist movement.

To the everyday onlooker, Tubman served as a nurse and used local plants to prepare natural remedies for soldiers suffering from “dysentery and infectious diseases,” but beneath the surface, she was also working as a spy under the orders of U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

Harriet Tubman began to conceive of her most ambitious slave liberation operation to date.

She worked in collaboration with Colonel James Montgomery, a white abolitionist who commanded the all-black 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. Their goal was to strike at the heart of South Carolina’s plantation economy, weaken the Confederate forces, and most importantly, free liberate hundreds of enslaved people.

The key to building their plan for the raid was intelligence. Tubman had built a network of informants— enslaved workers, boatman, and other scouts. These men knew the backwaters of the Lowcountry of South Carolina better than anyone.

With the help of her network of spies and informants, Tubman began to map minefields (where Confederates had purposefully planted torpedoes to destroy Union boats), and she identified key plantations for attack, as well as the raid’s logistics.

Soon, the plan was set and the raid was put into motion in the very early morning of June 1, 1863.

One of Harriet Tubman’s prayers was recorded on the wall of the Gibbes Museum exhibition below. It was not clear if this was a prayer she used before the Combahee River Raid, but I’d like to think it might have been.

The operation was comprised of 300 soldiers in the 34th USCT (2nd South Carolina Volunteers), the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, Harriet Tubman, Colonel James Montgomery.

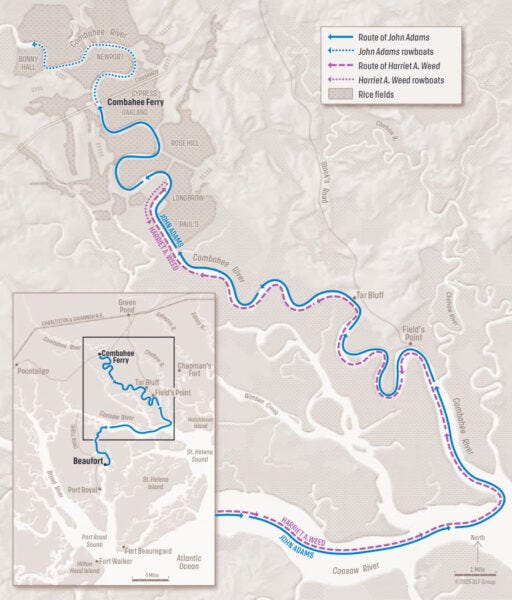

“Just after midnight”, the group steered Union gunboats — Harriet A. Weed, John Adams, and Sentinel — quietly up the 40-mile Combahee River in Southern South Carolina. See map below for geographical orientation.

The boats expertly navigated points in the river where Tubman had been informed there were likely torpedoes.

Unfortunately, one of the gunboats, The Sentinel, got stranded in a shallow sandbar as they navigated upstream, but that did not deter the raid operation. However, this meant the operation would have less capacity on their ships to liberate the plantation slaves.

Here are some photos I took of the J Henry Fair photographs that were included in the Harriet Tubman exhibition at the Gibbes Museum — that show the landscape where the raid took place:

Soon the Harriet A. Weed and the John Adams arrived at the entrance of the Combahee River at Fields Point, where “Confederate soldiers fled the scene at the arrival of Black soldiers.” Colonel Montgomery left a company of soldiers at Fields Point, and the operation continued upstream.

At a location called Tar Bluff, Confederates attacked, but the Harriet A. Weed gunboat opened fire on them, and scattered the soldiers.

The operation continued to the Combahee River Ferry — which is the site of the present day Harriet Tubman Bridge on US Highway 17.

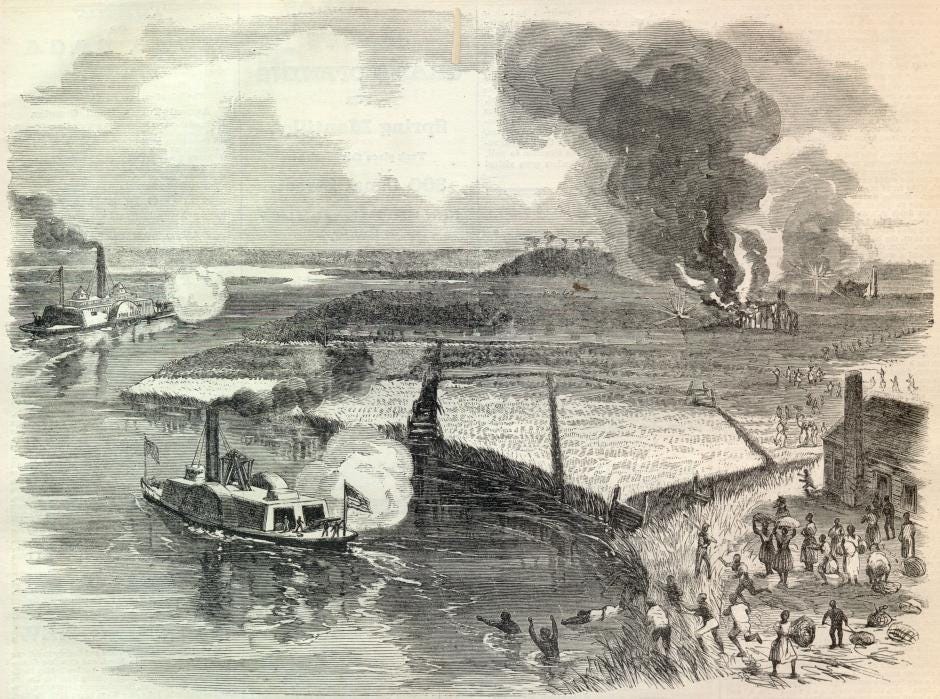

Around dawn, the Union soldiers began a coordinated attack on the man plantations that were situated on the river. They burned plantation homes, barns, rice mills, a cotton gin, and a sawmill.

The plantations that were attacked were owned by:

Mr. Oliver Middleton

Mr. Andrew Burnett

Mr. Wiliam Kirkland

Mr. Joshua Nichols

Mr. James Paul

Mr. Manigault

Mr. Chas. T. Lowndes

The slaves on the plantations heard the gunboat whistles coming up the river.

The Gibbes Museum exhibition did a great job of illustrating this very moment that the Union troops struck and offered a video reenactment (with live actors) of one of the plantation owners’ (Mr. Joshua Nichols’) recounting his perspective of the attack vs. an enslaved man’s (Manis Hamilton’s) perspective.

From this video, I learned that the plantation masters encouraged their slaves to run for the forest and “escape the Yankees, who will sell you to Cuba!” But the slaves knew better than to trust their masters. Instead, hundreds of enslaved people rushed to the Union gunboats. The plantation master would later recount that he couldn’t believe not a single slave stayed behind out of loyalty to him or his family, while they watched their plantation mansion burn. To us, looking back on this history, this is not surprising.

The freedman from the video was an 88-year-old former slave, Minus Hamilton, who was rescued by the Combahee River Raid. He recounted that he and his fellow enslaved workers were in awe of the black men aboard the Union gunboats in uniform. As he ran to the boats, all he could take with him were the clothes on his back.

In the 1869 biography written by Sarah Hopkins Bradford, Harriet Tubman was quoted about her account of this moment in the raid:

“I nebber see such a sight. We laughed, an' laughed, an' laughed. Here you'd see a woman wid a pail on her head, rice a smokin' in it jus' as she'd taken it from de fire, young one hangin' on behind, one han' roun' her forehead to hold on, t'other han' diggin' into de rice-pot, eatin' wid all its might; hold of her dress two or three more; down her back a bag with a pig in it. One woman brought two pigs, a white one an' a black one; we took 'em all on board; named de white pig Beauregard, and the black pig Jeff Davis. Sometimes de women would come wid twins hangin' roun' der necks; 'pears like I never see so many twins in my life; bags on der shoulders, baskets on der heads, and young ones taggin' behin', all loaded; pigs squealin', chickens screamin', young ones squallin'.”

Not only was Harriet Tubman instrumental in helping load over 750 slaves onto the gunboats, but she actively participated in the raid on the land as well.

Professor Edda Fields-Black shared in an interview with Bunk History:

“One of the first sources that I found as I was writing ‘Combee’ was the life story of Minus Hamilton, the 88-year-old man who tells his story a few weeks after the Combee River Raid. And from Minus Hamilton’s story, I wanted to tell not only Harriet Tubman’s story but the stories of the people she freed. And my goal was to tell the story of the Combee River Raid through their voices, through their eyes, through their perspectives. I ended up using the U.S. Civil War pension files. Here, the goal was to use them to reconstruct the community on the Combee before, during, and after the raid…

I must speculate here, and what I speculate is that the Union told the enslaved people who she [Harriet Tubman] was. And her presence facilitated the enslaved people in trusting the Union. We know, from some of the sources I’ve brought together in ‘Combee,’ that Harriet Tubman was on the ground in the raid, that she participated in the burning of buildings, and that she went to the slave cabins and coaxed the people there to come onto the boats and come to freedom. So how she convinced them to do that, we don’t know, but they did trust her, even if they didn’t know her entire backstory.”

Small boats were sent out to retrieve the slaves from the shore and bring them to safety on the gunboats. The slaves rushed to the small boats, at one point putting the gunboats in danger of capsizing. The small boats made several trips back and forth to load those who wanted to leave.

At the end of the operation, more than 750 enslaved people were rescued in the Combee River Raid — the largest liberation event of the entire Civil War. These men and women were brought to Beaufort, and then transported to a resettlement camp on St. Helena’s Island.

Harriet Tubman helped recruit about 150 of the newly freed men who were rescued in the raid to the Union Army.

The operation was a stunning success and it was written about in newspapers far and wide.

The pro-Union Commonwealth newspaper of Boston reported:

“Colonel Montgomery and his gallant band of 300 black soldiers under the guidance of a black woman, dashed into the enemy's country, struck a bold and effective blow, destroying millions of dollars worth of commissary stores, cotton and lordly dwellings, and striking terror into the heart of rebeldom, brought off nearly 800 slaves and thousands of dollars worth of property, without losing a man or receiving a scratch. It was a glorious consummation.... The colonel was followed by a speech from the black woman who led the raid and under whose inspiration it was originated and conducted. For sound sense and real native eloquence her address would do honor to any man, and it created a great sensation.”

The pro-Confederate Charleston Mercury newspaper reported:

“We have gathered some additional particulars of the recent destructive Yankee raid along the banks of the Combahee. The latest official dispatch from Gen. WALKER, dated Green Pond, eleven o'clock Tuesday night, and which was received here on Wednesday morning, conveyed intelligence that the enemy had entirely disappeared. It seems that the first landing of the Vandels [sic], whose force consisted mainly of three 'companies, officered by whites, took place at Field Point, on the plantation of Dr. R. L. BAKER, at the mouth of the Combahee River. After destroying the residence and outbuildings, the incendiaries proceeded along the river bank, visiting successively the plantations of Mr. OLIVER MIDDLETON, Mr. ANDREW W. BURNETT, Mr. WM. KIRKLAND, Mr. JOSHUA NICHOLLS, Mr. JAMES PAUL, Mr. MANIGAULT, Mr. CHAS. T. LOWNDES and Mr. WM. C. HEYWARD. After pillaging the premises of these gentlemen, the enemy set fire to the residences, outbuildings and whatever grain, etc., they could find. The last place at which they stopped was the plantation of WM. C. HEYWARD, and, after their work of devastation there had been consummated, they destroyed the pontoon bridge at Combahee Ferry. They then drew off, taking with them between 600 and 700 slaves, belonging chiefly, as we are informed, to Mr. WM. C. HEYWARD and Mr. C.T. LOWNDES. The residences on these plantations are located at different distances from the river, varying in different cases from one to two miles. On the plantation of Mr. NICHOLLS between 8000 and 10,000 bushels of rice were destroyed. Besides his residence and outbuildings, which were burned, he lost a choice library of rare books, valued at $10,000. Several overseers are missing, and it is supposed that they are in the hands of the enemy.”

Despite Tubman’s extraordinary serve to the Union efforts and to the emancipation of slaves, she was not a regular soldier and was only occasionally compensated for her work as a scout and a spy by the U.S. Government.

For over 3 years of service during the Civil War, she was given $200 (equivalent to $4,110 in 2024). Because of her “unofficial status,” those in charge had difficulties documenting her service and the U.S. government “was slow to recognize any debt to her.”

In the coming years, Tubman would continue her humanitarian work for both her family and formerly enslaved people, but without any compensation — which kept her in a perpetual state of poverty.

In 1865, Harriet Tubman returned to her home in Auburn, New York where took on boarders to make ends meet. One of those boarders, Nelson Davis, was a farmer and former black Union soldier, who (though 22 years Tubman’s junior) would become Tubman’s 2nd husband (her former husband had abandoned her for another woman in 1851). The couple would adopt a baby girl named Gertie in 1874.

Friends, family, and abolitionist admirers worried about Tubman’s state of poverty and endeavored to help when they could. Per above, one admirer named Sarah Hopkins Bradford, wrote a biography of Hariet Tubman’s life, which was published in 1869 and proceeds from the book went towards some income for Tubman and her family.

In 1874, Representatives Clinton D. MacDougall of New York and Gerry W. Hazelton of Wisconsin “introduced a bill to pay Tubman a $2,000 (equivalent to $55,600 in 2024) lump sum "for services rendered by her to the Union Army as scout, nurse, and spy", but it was defeated in the Senate.”

Tubman’s husband died of tuberculosis in 1888, and she was eligibles to receive widow’s pension funds which helped her financial situation.

By 1911, Harriet Tubman was 89 years old. One New York Newspaper described her as “ill and penniless” and she sadly died of pneumonia on March 10, 1913.

Just before she died, she quoted the Gospel of John to those in the room: "I go away to prepare a place for you." Tubman was buried with semi-military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn.

While not properly compensated or properly celebrated as the hero that she was in life, in the century since her death, Harriet Tubman has become a prominent national historical figure — with national parks and monuments named in her honor. She is also the inspiration for many artists and the subject of many works of art — including some of the powerful art I saw at the Gibbes Museum in their exhibit. See below.

Here are ways to support Harriet Tubman’s extraordinary legacy:

Support Historic Sites Honoring Tubman’s Life

Help Preserve the Combahee River Landscape (SC)

Fund Educational Work About Tubman’s Story

Support Museums Presenting Tubman’s Legacy

If you voted just “OK” on the newsletter today, I want to hear from you! Reply to this email and send me your feedback. :)

➳ Sources — Freedom by Moonlight: Harriet Tubman and the Combahee River Raid, 162 Years Later

“Combahee River Raid (1863).” The Civil War Monitor, https://www.civilwarmonitor.com/article/combahee-river-raid-1863/. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Fields-Black, Edda. “How a Raid in SC Freeing 700 Slaves Became a Pulitzer Prize-Winning Book.” Alaska Beacon, 19 June 2025, https://alaskabeacon.com/2025/06/19/how-a-raid-in-sc-freeing-700-slaves-became-a-pulitzer-prize-winning-book/#:~:text=Fields%2DBlack%20first%20learned%20about,the%20river%20and%20to%20freedom. Accessed 21 June 2025.

“Harriet Tubman.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/harriet-tubman.htm. Accessed 22 June 2025.

“We Called Ourselves the Combahee.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/we-called-ourselves-combee.htm. Accessed 21 June 2025.

“Documenting Harriet Tubman’s Leadership: Pulitzer Prize-Winning Edda L. Fields-Black on the Combahee River Raid.” Bunk History, https://www.bunkhistory.org/resources/documenting-harriet-tubmans-leadership-pulitzer-prize-winning-edda-l-fields-black-on-the-combahee-river-raid-ms-magazine. Accessed 22 June 2025.

“Harriet Tubman.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harriet_Tubman. Accessed 22 June 2025.

Zauzmer, Julie. “African American History Museum Unveils Previously Unknown Harriet Tubman Photo.” DCist, 25 Mar. 2019, https://dcist.com/story/19/03/25/african-american-history-museum-unveils-previously-unknown-harriet-tubman-photo/. Accessed 21 June 2025.

Hi Kate

Another impactful event occurred at this same spot (Tar Bluff). My xGreat uncle was there and witnessed the death of John Laurens. Strange in that this is in the middle of nowhere

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/combahee-river

Thanks

Drayton Gaillard