#42: Charleston's 3 Tea Parties, Hessian Troops, and a Lecture on "Race, Rice, and Rebellion in South Carolina"

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #42 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

I’d like to extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers of the SC History Newsletter community below! Woohoo!

tuere.wiggins

waddell.sarah2

mitch.wetherington

frstldy

scharps04

jay.jenkins

hem8885

scottie4109

jbaxley33

rivedal

sarah.cokeley

tumblinw

stephaniehorres

londonfmam6

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Thursday, April 11th at 4:00 pm | “Celebrating 50 Years: Black Majority: Race, Rice, and Rebellion in South Carolina 1670-1740” | Mace Auditorium - College of Charleston | Charleston, SC | FREE and open to the public

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

While the Boston Tea Party in 1773 may be the most iconic in our American Revolutionary history knowledge, did you know that there were 3 Charleston Tea Parties?

Tea was a staple of life in colonial times. According to Cornell University professor Mary Beth Norton, American colonists were “the greatest tea drinkers in the universe.” And this was especially true in port cities like Charleston. Apparently all together, American colonists drank 1.2 million pounds of tea per year. And of this huge amount of tea, approximately 90% of it was smuggled into the colonies (note that Founding Father John Hancock was a tea smuggler).

The tea smuggling business led to financial troubles for the British East India Tea Company, which had “17 million pounds of unsold surplus tea” in its warehouses. The Tea Act, passed by British Parliament on May 10, 1773, granted the British East India Company (1) a monopoly on tea sales in the American colonies, (2) an exemption on the export tax, and (3) a “drawback” (refund) on duties owed on certain surplus quantities of tea in its possession. With the new Tea Act in place, British East India Company tea was shipped to the colonies at a reduced rate, which undercut the business of American merchants (and tea smugglers), which infuriated the colonists.

Even before the Tea Act, tensions between Parliament and the colonists had been brewing for over a decade. In the 1760s, Britian was deeply in debt, and proposed a series of taxes on the American colonies — which Parliament felt justified in doing given that “much of the country’s debt was earned fighting wars on the colonists’ behalf.”

First there was the Stamp Act of 1765 that taxed colonists on virtually every piece of printed paper they used. Then the Townsend Acts of 1767 that taxed essentials such as paint, paper, glass, lead and tea. The colonists were furious at being taxed without having any representation in Parliament. As tensions flared between colonists and the British, the Boston Massacre occurred in 1770, which killed 5 colonists and wounded six. Rage against the British was about to reach a fever pitch.

Fast forward once again to May 1773, and the passing of the Tea Act.

Garden & Gun writer Kinsey Gidick in her article Did Charleston’s Tea Party Happen Before Boston’s? vividly explains the circumstances that led to Charleston’s Tea Party:

Now, put yourself in the shoes of the Charlestonians. You love tea. You’ve got to have it. There’s no way you’re inviting the Pinckneys or Rutledges over for supper without the finest and freshest Bohea, Singlo, or Hyson [popular tea] in your porcelain cups. But now Parliament is trying to play you for a fool by attempting to regain a monopoly on tea sales while taxing you without representation. Adding insult to injury, you get word that Captain Alexander Curling’s ship, the London, is about to dock at Charles Towne Harbor with 257 chests of East India Company tea. Now you’re boiling over with rage.

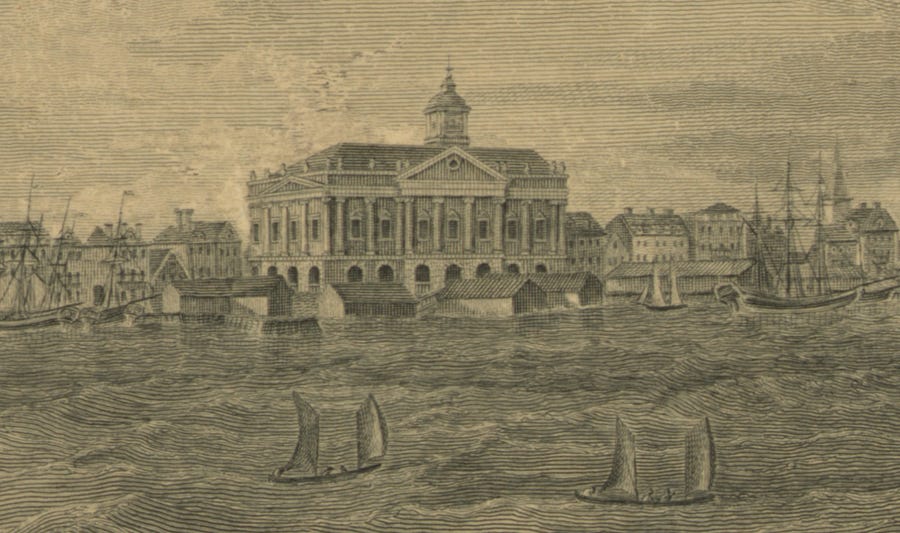

Indeed, on December 1, 1773, an East India Company ship named the London sailed into Charleston’s harbor carrying 257 chests of tea. In the weeks leading up the London’s arrival, Charleston’s papers had been fuming over the latest taxes imposed by Parliament. The people of Charleston refused to allow the tea from the London to be brought to shore. For two days, the London sat in the harbor while the city leaders decided what to do. On December 3, the city held a meeting in the Exchange building. Those in attendance decided to boycott the importation of tea, but still had to convince Charleston’s merchants, “who would stand to lose money on the deal,” to join them in the boycott. Negotiations took 3 weeks, but ultimately the merchants were convinced, and a tea boycott began.

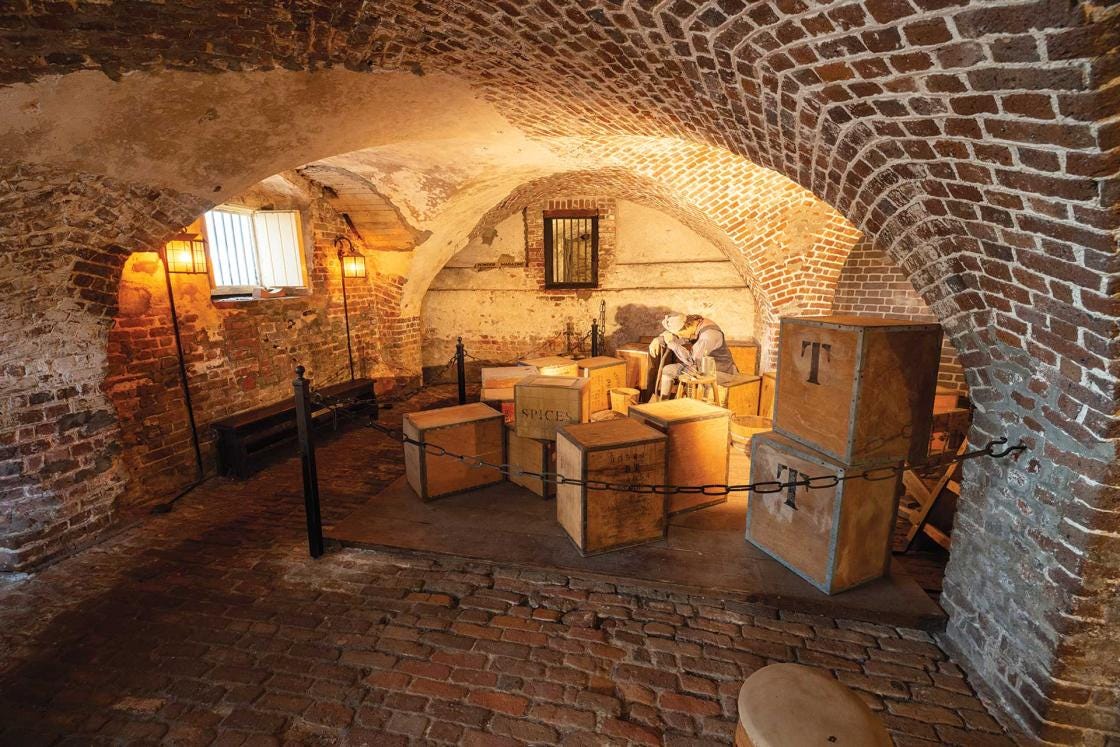

While the Charleston boycott happened before Boston’s did, it was not as climactic. Rather than throwing the tea into the Charleston Harbor, the Charleston boycotters unloaded the tea chests and stored them in the Exchange building basement. Fun fact: the tea chests sat in the basement for next 3 years until they were sold “to fund America’s war for independence.”

The Boston Tea Party would happen within the very same month on December 16, 1773. Other “tea parties” would happen in colonial cities in Maine, North Carolina, New Jersey, Maryland, and beyond.

There would be 2 other Charleston Tea Parties. The 2nd Charleston Tea Party happened in July 1774 and involved the British merchant ship Magna Carta. An angry mob of protestors confiscated “one full chest and two half-full chests of tea,” which they also stored in the Exchange Building.

The 3rd and final Charleston Tea Party involved the ship the Brittania, which arrived in Charleston on November 1, 1774. This time, Charlestonians took no chances with this shipment. Captain Ball of the Britannia was forced to dump the tea onboard into Charleston Harbor. As reported in the South Carolina Gazette, “at noon, an oblation was made to NEPTUNE, of the said 7 chests of tea.” A huge crowd of Charlestonians, who had gathered for this confrontation, gave “three hearty cheers” as the tea was dumped into the waters of the harbor.

In a fun piece of living history, this past December 2, 2023, Charleston’s Powder Magazine Museum reenacted the city’s 1773 tea party protest at a live outdoor performance at the intersections of Broad and East Bay Streets. The reenactment—which was a partnership with Oliver Pluff & Co. tea company, the Old Exchange Building & Provost Dungeon, and the South Carolina Historical Society — marked the 250th anniversary of the historic event.

II.

Did you know that a significant portion of the army that besieged Charleston in 1780 were Hessian soldiers from Germany?

At the beginning of the rebellion in the America colonies, the British Crown reinforced its troops and contracted with several of the leaders of the “German principalities to hire out approximately 20,000 troops for service in America.” These men came from places such as “Brunswick, Anspach-Bayreuth, Waldeck and Hesse-Hanau.” The largest contingent came from Hesse Cassel, and as a result these men were universally referred to as “Hessians.” They were effective, professional soldiers and often “performed expertly” for the British.

Hessians made up a significant portion of the army that besieged Charleston in 1780 and comprised a sizable part of the garrison that occupied the city until December 1782. Strategic Charleston forts and defenses were often manned by Hessian soldiers.

Because America contained a large number of German settlers, Hessian troops melded well with the local populace. This often created problems for their officers “as desertions were frequent.”

In 1777, a Hessian soldier named Johann Conrad Döhla journeyed from Anspach-Bayreuth (a principality in present-day Germany) to North America to fight alongside the British Army during the Revolutionary War. Döhla fought from New York to Virginia and kept a diary of his experiences along the way. He recorded the daily activities of a soldier's life, anecdotes of his fellow soldiers, and many other unique observations about the foreign people and places he encountered. Per above, Döhla event recounts the punishment of a deserter.

The following excerpt from his journal includes his entries during the month of July 1781, the summer before the surrender at Yorktown — and includes mentions of South Carolina:

IN THE MONTH OF JULY

2 July. We were relieved during the morning by a command of Hessians.

6 July. During the evening Private [Johann] Bär, of Quesnoy's Company, deserted from the camp without his uniform, dressed only in his linen blouse.

7 July. On today's date the besieged city of Ninety-Six in South Carolina, and the important pass between Cambridge and Charleston, was relieved by the English troops under Colonel Tarleton, and the Americans were driven back so that they had to abandon the siege.

8 July. During the afternoon the deserter Bär was returned to the regiment by the so-called Royal Refugees. They had captured him twenty miles from here.

10 July. The English fleet, which consisted primarily of transport and provisions ships, and had two warships and three frigates for an escort, was attacked by the French Admiral La Motte as the English were coming from Saint Eustatius in the West Indies en route back to England. One warship of seventy-four guns and two frigates (one of forty and one of thirty-six guns), and thirteen transport ships, carrying more than twenty-one hundred men, were captured. The rest were routed and, after a three-hour resistance, fled.

11 July. Punishment was carried out by the regiment. The deserter Bär, of Quesnoy's Company, today ran a gauntlet of three hundred men with switches, twelve times. At noon today the command [sent] to Greenbridge returned. They brought many cattle with them. These were slaughtered and divided among the regiments. Two men of the Ansbachers and two from our regiment, namely, Private [Johann Paul] Währl and Private Dressel, of Eyb's Company, were missing from this command.

12 July. Bär again had to run the gauntlet twelve times.

13 July. We had no shortage of provisions here at New Portsmouth because the inhabitants brought them, mostly fresh and plentiful, into the camp. All the foodstuffs were cheap except that a quart of rum cost about half a Spanish dollar, or in German money, one Franconian gulden. Here, surprisingly, crabs are caught on dry land and hay grows on the trees. For this reason: here many small crabs are found that are called sand crabs. These hide in the sandy soil, in which there are many small holes, and as soon as it rains a little, these crabs come out in numbers from these holes so that the ground is covered with them. We have gathered and cooked an entire kettle full of them. They are a kind of water crab, but somewhat smaller, and they turn red when cooked and taste like ours. Concerning the hay that grows on trees, the following must be understood. There is this moss, long and soft, which frequently hangs down from the limbs, more than an ell in length, and which grows abundantly on the trees. This is gathered like fodder by the inhabitants and stacked for feeding the cattle during the winter. In Virginia there is also much clipped money because of a shortage of small change. One Spanish dollar is divided into eight parts; the piaster, however is divided into two or four parts. The inhabitants of Virginia are built tall and strong and appear rather pallid due to the great heat. Toward us they were rather complaisant and showed more respect than in other provinces. Especially, the Virginia females showed great affection for the Germans.

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

I.

“WE the undersigned, inhabitants of this province, being new fully convinced, that we have vainly flattered ourselves, with hopes of the repeal of an act of parliament of Great-Britain, passed in the year 1767, imposing a duty on tea imported from thence, for the purpose of raising a revenue upon us, in America, without our consent, DO hereby solemnly promise and agree, each for him or herself, that we will not, either directly or indirectly import, buy or sell, or any way encourage or countenance the importation, buying or selling, any teas that will pay the aforesaid duty: And that we will not purchase any goods of any person or persons whosoever, that shall hereafter import, buy or sell any such teas: And this we do, because we conceive, that the payment of such duties, will be acknowledging a power which the British Parliament hath assumed, and which we deny them to have under our excellent constitution, “to tax us against our consent.”

—1773 petition in response to the British ship, the London, bringing tea into Charleston’s port — published in the Charleston Gazette

Sources used in today’s newsletter:

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!