#75: Freedman's town of Mitchelville, Chicora College for Young Ladies, and a lecture on "the fascinating life of William Hix"

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #75 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

autopartsupullclt@yahoo.com

folktra@gmail.com

ngcummings09@comporium.net

gbarks1@comcast.net

susan.tucker@me.com

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Refer your friends to SC History Newsletter and win a “Best of South Carolina” gift basket!

Hi everyone! I am SO grateful and excited that there are now 478 free subscribers (and 15 paid!) for the SC History Newsletter. Y’all are amazing!! I have a goal for us to get to 1,000 subscribers by May 20th. Can you help me achieve my goal? And let’s make it fun by making it a contest!

HOW TO ENTER: By using the button below, you can share a unique link to the SC History Newsletter with your friends. Each time one of your friends signs up for the newsletter from your unique link, I can see on my dashboard!

WINNER: The person who refers the most people who sign up for the SC History newsletter will win the “Best of South Carolina” basket on May 20th! I will keep everyone posted on the “standings” as they come in.

THE PRIZE: The basket of goodies (valued at $100) will include iconic sweet & savory South-Carolina made goods — and a few other surprises as well!

Start sharing today! Thank you so much!

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Tuesday, April 30th at 12:00 pm | “The Fascinating Life of William Hix: Laurens Artist, Photographer, Industrialist & Informant of the Civil War” | The Magnolia Room at the Laurens County Museum | Laurens, SC | FREE Admission

“Laura Dunning Elliott, an independent historian, author and researcher from Gadsden, Alabama will present the history of a local photographer and artist — William Preston Hix. Hix, a well known artist in his time and one we are sure that many are not aware of his history. Hix, a native of Laurens County, was born in 1836 and grew up on South Harper Street in Laurens County. His artistic talents took him to Columbia where he went into a partnership with Richard Wearn known as Wearn and Hix – a photography studio well known for their illustrations of the destruction of Columbia. From there he enlisted in Company A - 3rd South Carolina regiment and fought in the Civil War. Several years later, his work took him to New York where he worked in the development and sales of electrical service under Thomas Alva Edison.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

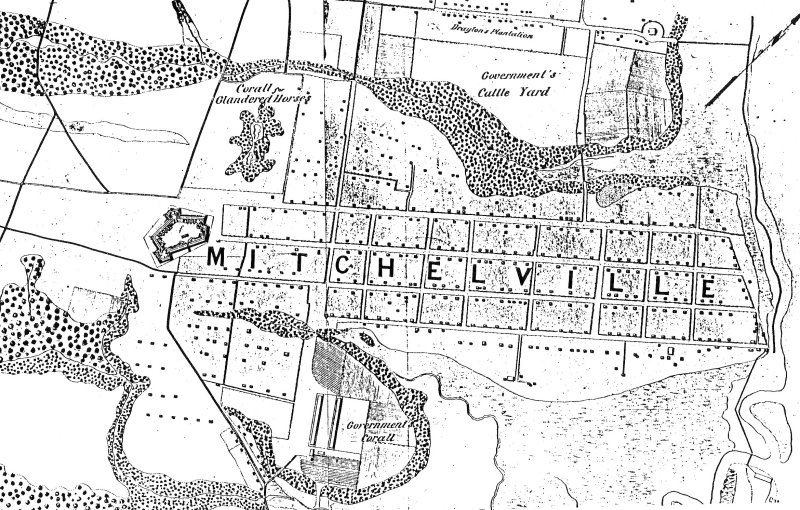

Did you know that the town of Mitchelville on Hilton Head Island was the nation’s first self-governing town for freed African workers after the Emancipation Proclamation?

Before the Civil War, cotton and rice were highly valuable crops grown on the Sea Islands of South Carolina.

Enslaved people living on the Sea Islands arrived “mainly from West Africa, including Cameroon, Angola, and Sierra Leone.” Due to the isolated nature of the Sea Islands, the enslaved workers were able to “retain many of their traditions from home, as many were only one or two generations removed from Africa. It is reported that Hilton Head, at times, resembled a West African homeland and resulted in the emergence of Gullah culture (the combination of numerous West African cultures into one).”

On April 12, 1861, the Civil War commenced with the Confederate Army attack on the Union Army’s Fort Sumter, off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina.

On November 7, 1861, Union forces successfully attacked and captured two Confederate forts (Fort Walker and Fort Beauregard) and the Sea Islands of South Carolina in the Battle of Port Royal, which lasted five days.

Hilton Head Island, specifically Drayton Plantation, immediately became the headquarters for the Union Army.

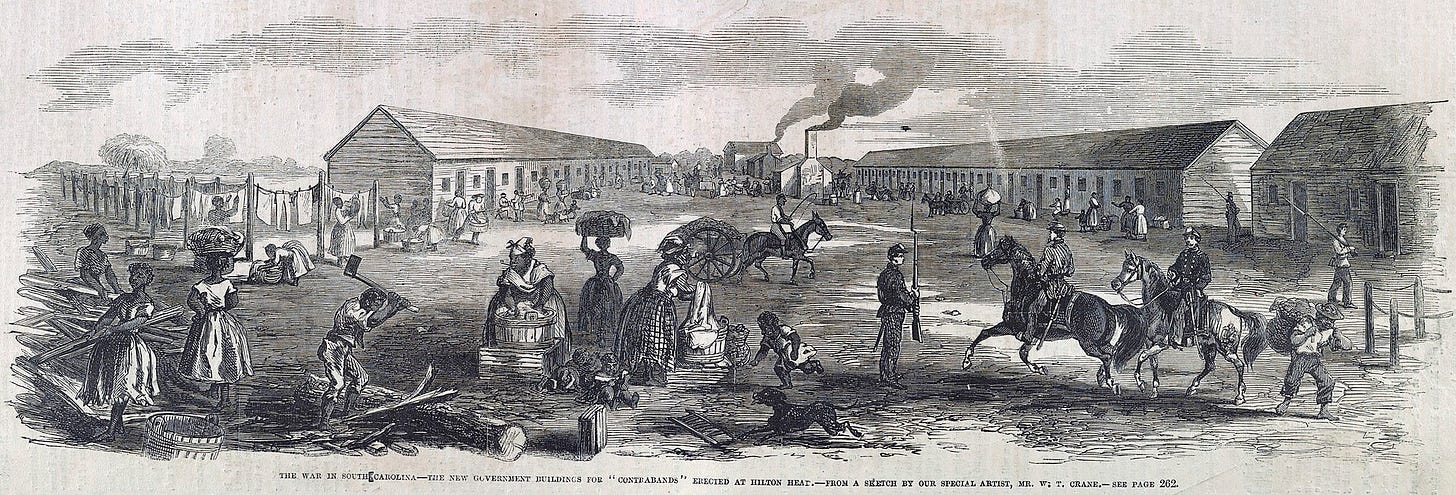

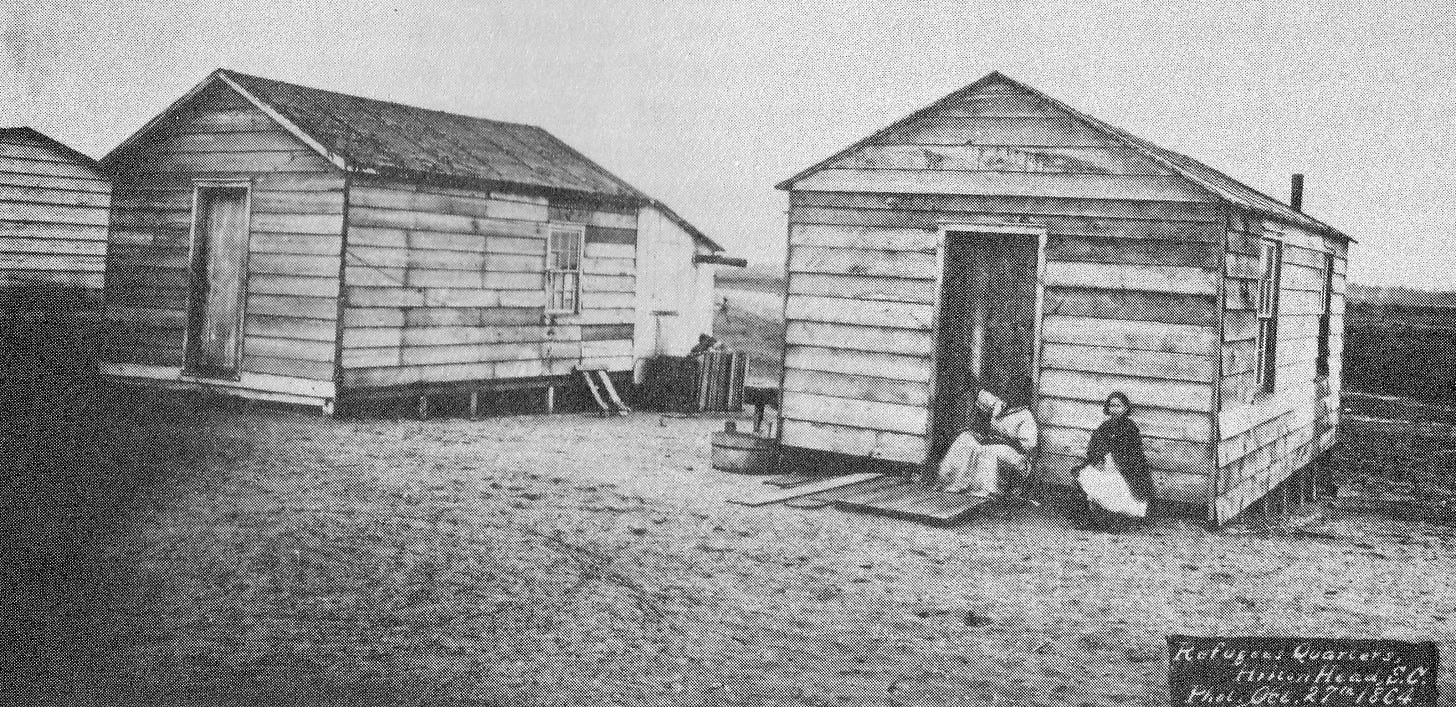

Formerly enslaved residents, officially known as “contrabands”, began to arrive in Hilton Head from the mainland and surrounding islands to seek refuge with the Union Army. They showed up by the hundreds at the newly formed Union Army Headquarters on Hilton Head Island.

Once registered at the headquarters, the “contrabands” were assigned to barracks and began their new lives on the base.

The new residents began working for wages and assumed jobs for the Union Army including “unloading supply ships, serving as waiters and housekeepers for Union officers, washing clothes, working in the commissary, bake shop, garden, and hospital.”

Since cotton was still the leading export of the United States, it continued to be harvested by the formerly enslaved, but now for a wage.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Port Royal on Hilton Head Island, wealthy white residents and plantation owners fled inland and “took as many slaves as they could with them, leaving behind over 10,000 slaves.”

Samuel DuPont, Captain in the US Navy, reported:

“you can form no idea of the terror […] Beaufort is deserted and the [white residents and plantation owners] flew in panic, leaving public and private property, letters, portfolios, all their regimental archives, clothes, arms, etc.”

US Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase sent an agent, Edward Pierce (who supervised the work of contrabands in Virginia), to report on the status and conditions of the formerly enslaved residents.

During his two-week tour, Pierce checked on the conditions and abilities of the formerly enslaved, reporting back that they should have wages, better food, and education. He also reported that the formerly enslaved were in danger of destitution, as food and clothing were becoming scarce. Sexual assault of formerly enslaved women had also become an issue, as African American women had been taught it was a crime to resist white men. The Army needed a better solution.

As a result of Pierce’s report, northern societies and organizations responded with generosity. When Pierce returned to the Sea Islands, he “brought with him 60 teachers and superintendents, established schools for the formerly enslaved, and suggested the formation of freedmen’s aid societies. He also oversaw the government’s efforts on the ground to further these efforts, which became known as the Port Royal Experiment.”

Charlotte Forten, the first Black missionary teacher in Port Royal, was present in Hilton Head on the day the Emancipation Proclamation was read publicly for the first time in South Carolina — and gave an account of this historic day in an article for Atlantic Magazine:

“There was an eager, wondering crowd of freed people in their holiday attire with the gayest of head-handkerchiefs, the whitest of aprons, and the happiest of faces. The band was playing, the flags streaming, everybody talking merrily.” Thousands gathered to hear President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation read publicly for the first time in South Carolina; Forten called it “the most glorious day this nation has yet seen.”

It is important to note that the Emancipation Proclamation did not free millions of slaves behind Confederate lines, including those in the South Carolina mainland.

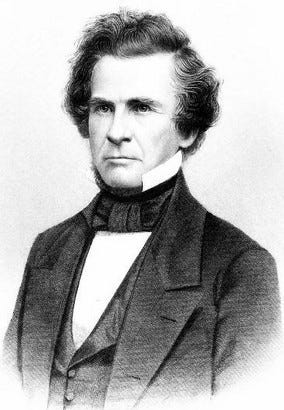

Union Army Major General Ormsby Mitchel arrived in Hilton Head Island to replace General Hunter (who went on leave) and assumed command.

Once Mitchel saw the living conditions of the formerly enslaved “contraband” in the refugee barracks, he gave orders for a new “negro village” near Drayton Plantation to be built by and for the freedman/refugees, complete with homes, police protection, and a school. This effort became known as the “Port Royal Experiment” and was largely regarded as a precursor to the Reconstruction period.

General Mitchel visited First African Baptist Church and addressed members with a rousing speech, setting the vision for the new freedman’s town:

“What will you do with the black man after liberating him?” We will make him a useful, industrious citizen. We will give him his family, his wife, his children – give him the earnings of the sweat of his brow, and as a man, we will give him what the Lord ordained him to have. This experiment is to give you freedom, position, homes, your families, property, your own soil. It seems to me a better time is coming … a better day is dawning.”

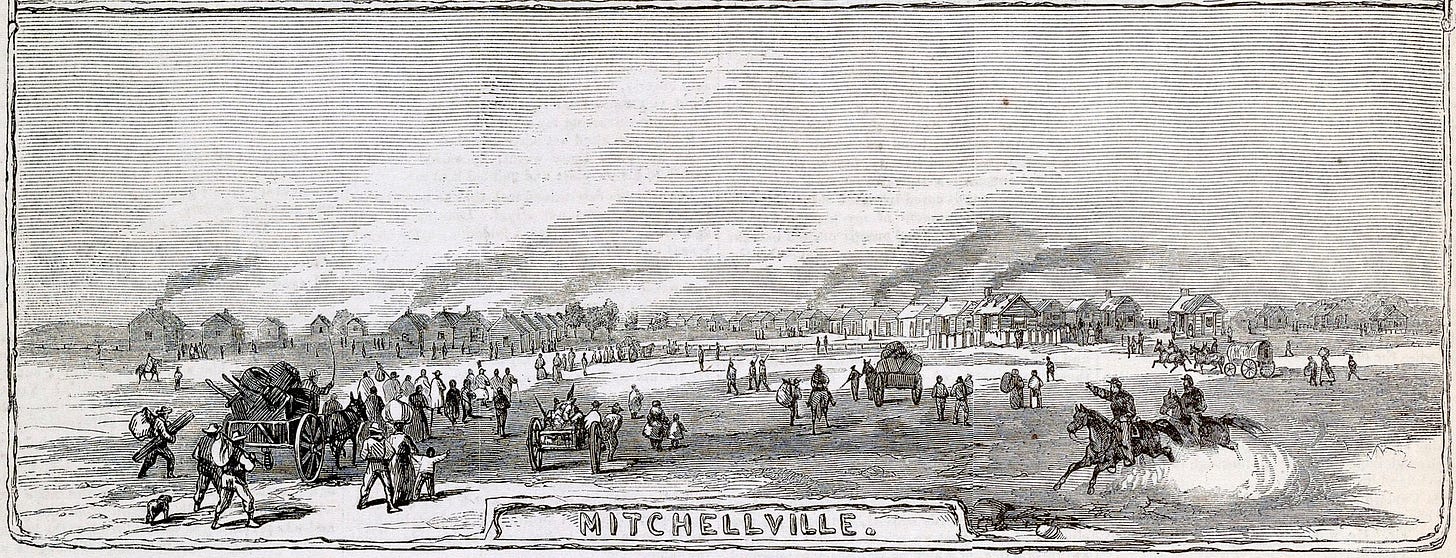

General Mitchel held a contest between the Union Army engineers and the freedmen to find the best cabin design; the design by the freedmen won and construction started on the new town.

The homes, each on a quarter-acre lot, were initially built by approximately 50 freedmen using wood from a sawmill and other raw materials.

The freedmen were building up to six homes per day and were led by a black carpenter and a white engineer, who helped facilitate the acquisition of supplies.

The homes also had land for growing crops like sweet potato and corn and other family activities.

General Mitchel died only six weeks after arriving in Mitchelville from yellow fever — he never saw the town he envisioned come to fruition.

As the first self-governed town for the formerly enslaved, Mitchelville was named posthumously after its founder, General Ormsby Mitchel.

It was a fully functioning town with a mayor, councilmen, a treasurer and other officers, who all oversaw every aspect of Mitchelville, from town disputes to sanitary regulations.

The town of Mitchelville also established the first compulsory education law in South Carolina, requiring education for every child from the ages of 6-15 years of age.

At its height, the town stretched to over 200 acres on the former Fish Haul Plantation, which borders the shore.

The US Army Headquarters remained the central source of employment and life for the residents of Mitchelville, as most residents worked for the military.

With the end of the Civil War, the Union Army began to leave the island, which led to many freedmen leaving too — either following the Army for jobs, moving on to reclaimed plantations for wage jobs, or moving further inland.

At the same time, the schools began to close, the barracks emptied, and the missionaries, once a sign of forward progression, left also. For the first time in six years, the freedmen who remained in Mitchelville were on their own.

In spite of these changes, it appears that Mitchelville was still an active village. An AMA teacher described Mitchelville in 1867:

“There are several large plantations upon which are small settlements, but the greater part of the colored population of the island are located a short distance from Hilton Head [meaning the old military base] at a place called Mitchelville… It is an incorporated town, regularly laid out in streets and squares. About 1500 inhabitants, not a single white person. There are three churches – two Baptist, one Methodist, two schools which are taught by A.M.A. teachers.”

Although the military had left, taking jobs with them, many of the African American residents turned to subsistence farming.

Some formed collectives, joining together to rent large plantations from the government.

Many of the freedmen were able to save their wages until they had the money to purchase land. However, many of the lands being planted by the freedmen were no longer available. Additionally, many lands purchased by freedmen in good faith, were returned to their Southern owners, with the blacks divested of their interest.

The Drayton Plantation (on which Mitchelville was located) was returned to the heirs of its former owner in April 1875, with the federal government deed failing to provide any protection for Mitchelville. The Drayton heirs, however, were not interested in planting the lands and began to sell it off to anyone interested in making purchases – including many freedmen.

It was during the last quarter of the nineteenth century that most, if not all, of Mitchelville was purchased by an African American man, March Gardner. March, while illiterate, was very successful – and apparently well respected. He placed his son, Gabriel, in charge of Mitchelville, which at this time also included a store, cotton gin, and grist mill. March also trusted Gabriel to have a proper deed made out. Instead, Gabriel took advantage of his father, eventually obtaining a deed in his own name and then transferring the property to his wife and daughter.

Over time the Mitchellville land was sold to a man named Roy A. Rainey of New York — who purchased the land on Hilton Head Island for hunting.

As more and more of Hilton Head Island was sold, the black population was reduced from the nearly 3,000 on the island in 1890 to only about 300 in the late 1930s.

By the early 20th century, Mitchelville no longer appeared on maps of the area. Fish Haul Plantation and the land that was once Mitchelville were sold to the Hilton Head Company in 1950.

Mitchelville was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988 (as the Fish Haul Archaeological Site), making the site important to preserving and understanding the nation’s difficulties during Reconstruction.

Today, Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park (HMFP) endeavors to “educate the public on the compelling story of its inhabitants and their quest for education, self-reliance and inclusion as members of a free society.”

In recent years, Priscilla Mitchel and Johnnie Mitchell are two women who campaigned heavily for the creation of the Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park and were drawn together by their very special shared history and friendship. Their shared last names (if spelled slightly differently) are no coincidence. Priscilla, 53, is the direct descendant of General Mitchel, after whom the town is named, and Johnnie, 65, is the direct descendant of slaves he freed.

In a BBC.com article from 2012, Johnnie explained how she got her last name: "Ex-slaves tended to take the names of good white people who had been nice to them," re: her husband's slave ancestors were named after the general.

"I definitely credit everything, my life situation, my children's good fortune, my family, to General Mitchel - that's why I'm passionate about it, because one person can make a difference," says Johnnie.

Priscilla, from Connecticut, says her relative gave his life for the freedom of others, having died of yellow fever 18 months after establishing Mitchelville:

"I've been a public school teacher for years and worked a lot in social justice issues, so I'm so proud of him - he's my hero…He saw Africans and other people as equals when they were mostly looked down upon... they deserved a house with a fence and garden, and that's what he gave them."

From their website: “With no other site serving as such a template or illuminating the authentic story of the place where freedom began for America’s Black citizens, Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park (HMFP) is uniquely positioned to broaden the awareness and recognition of its rich story.”

Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park (HMFP) provides feature exhibits, signature events and guided tours of Historic Mitchelville. In addition, it continues to enhance knowledge of Mitchelville through lectures, forums, and related cultural experiences. The park hopes to expand to “include replicas of the historic homes, churches, stores and other structures of Mitchelville for future generations to learn from.”

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

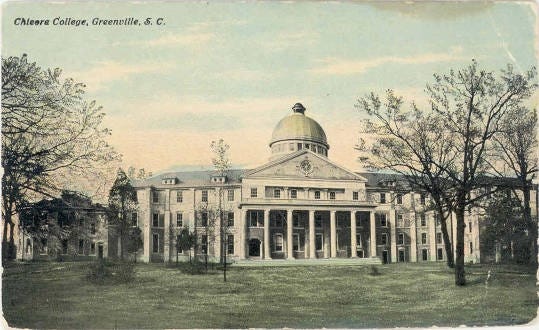

Did you know that the Chicora College for Young Ladies used to dominate the hillside of what is now the West End of the city of Greenville?

(Note from Kate: Thank you to of the South by Southeast Substack Newsletter (and avid SC historian himself) for this topic recommendation! I live in Greenville and can’t believe that this beautiful college occupied essentially the whole west end of the city in the early 1900s!)

Chicora College (also called Chicora College for Women, and Chicora College for Young Ladies) was a Presbyterian women's college in Greenville and Columbia, South Carolina.

In 1893, the First Presbyterian Church in Greenville, South Carolina, decided to start a college for women.

On August 12, 1893, the board of trustees was established for the Greenville Female Seminary with E. A. Smith as president. On September 20, 1893, it opened as the Chicora College. They selected the name Chicora “for the first Native American tribe that explorers met on the coast of South Carolina.”

The college started in a house rented on McBee Avenue in Greenville. Later, a property known as McBee Terrace was purchased on the west side of the Reedy River. The new college campus consisted of “16 acres that went from Camperdown Street to River Street and overlooked the river.”

The campus expanded to include “a dormitory, administrative buildings, a president's house, and a 1,200-seat domed octagonal auditorium. Its grounds had landscaping that extended down to the river. The campus was accessible by the Greenville and Columbia Railroad.”

Tuition for the college was $38 a year or $160 with room and board. The college's enrollment was around 200 students.

The religious influence at Chicora was of "first importance". Its students were not allowed to write letters or speak on Sundays and could not have visits or any communication from young men. Its motto was "Non ministrari sed ministrare" or "Not to be served, but to serve".

In 1897, the school’s course catalog for the first time called the institution the “Chicora College for Young Ladies.”

Students at Chicora College studied the liberal arts, modern and classical languages (French, Italian, German, and Spanish), Bible studies, the sciences (chemistry, natural sciences, and physics), photography, physical culture (gymnastics), domestic science/home economics, general elocution, and business skills such as bookkeeping and typing. Students could pay extra to study the "ornamental arts", including drawing, elocution, and music. Students were also taught a variety of sports.

The textile mills of Greenville began to decline in the early 20th century, and this negatively impacted the city's West End where the college was located.

In 1914, the college moved to Columbia, South Carolina, and merged with The College for Women in Columbia.

The college retired its debts by selling its Greenville campus. The school was renamed Chicora College for Women and it opened for students in 1915.

What happened to the school’s former beautiful buildings in Greenville? The auditorium building of the original campus in Greenville burned in 1919. The former college's remaining buildings were eventually demolished.

The Hampton-Preston House, the school’s former campus in Columbia, is now a history museum that includes a recreation of dormitory rooms as they existed in 1915.

The Hampton-Preston House was also listed in the National Register of Historic Places on July 29, 1969.

In 1930, the Chicora College for Women eventually merged with Queens University of Charlotte.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“There are four tenets that are guiding Mitchelville interpretation: freedom, democracy, citizenship and opportunity. These are American ideals. They don't get old. They don't get tired. They do get threatened from time to time. They embody the experience of the people who were here."

—Ahmad Ward, the executive director of Hilton Head's Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park

Mitchelville article sources:

“Our Story - Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park.” Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park, https://exploremitchelville.org/our-story-2/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

Jackson, Peter. “Mitchelville: The Hidden Town at Dawn of Freedom - BBC News.” BBC News, BBC News, 27 Jan. 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-16754502. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

Chicora College article sources:

Bainbridge, Judith. “Chicora College leaves Greenville.” Greenville News, 18 Nov. 2017, https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news/local/greenville-roots/2017/11/18/chicora-college-greenville-sc/875960001/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

“Chicora College.” Wikipedia, 30 Nov. 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicora_College. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

“Where GVL Women Went to College in 1898.” GVLtoday, GVLtoday, 21 Dec. 2017, https://gvltoday.6amcity.com/gvl-women-went-college-1898. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

Waugh, Barry. “Genetic History of Chicora College.” Presbyterians Of The Past, September 2016, https://presbyteriansofthepast.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Genetic-History-Chicora-College-11x17-PDF-9-29-2016.pdf. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

Waugh, Barry. “Chicora College for Women.” Presbyterians of the Past, 13 Mar. 2020, https://www.presbyteriansofthepast.com/2020/03/13/chicora-college-women/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!