#147: The First Memorial Day, List of SC Memorial Monuments, and Farm-to-Table Colonial Meal at Historic Camden

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, upcoming SC historical events, and other South Carolina recommendations.

Dear readers,

Happy Memorial Day!

Today, we salute all those who died in the line of service — in defense of the freedoms we hold dear.

I am excited to re-issue my SC History Newsletter #57 below which shares the history of what historians believe was the FIRST Memorial Day celebration in America — and it happened right here in South Carolina.

Sincerely,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Support the SC History Newsletter by considering heritages teas (inspired by South Carolina and American history!) from our fantastic sponsor Oliver Pluff & Co. — click on their beautiful ad below! :)

➳ Housekeeping for new subscribers!

New friends! There are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and more! See our archive here!

Send me your comments or topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Have additional ideas or feedback? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Keep the conversation going and join over 100 other subscribers by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here!

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

Love the SC History Newsletter? Please click the button below to share with a friend!

➳ Featured Upcoming SC History Events

🗓️Saturday, May 31st at 7:00 pm

📝 Farm-to-Table Colonial Meal at Historic Camden

📍Historic Camden | Camden, SC

🎟️$75 per person

💻 Website

From the event website:

Meet & speak with Chef Justin Cherry as he creates this simple farm to table colonial meal which showcases South Carolina’s traditional fare. The dinner will be completely prepared using 18th century methods, baked, & roasted in Historic Camden’s own wood-fired oven and open-hearth spit.

Live music and selection of complimentary wine served with dinner!

➳ 🗓️ Paid subscribers get access to my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

➳ The First Memorial Day

Note: this is a re-issuing of SC History Newsletter #57 from April 2024:

The Civil War produced unimaginable tragedy. 600,000 to 800,000 Union and Confederate soldiers died in the “single bloodiest military conflict in American history.”

The United States had to find a way to honor those who had died in the war. The first national commemoration of Memorial Day was held in “Arlington National Cemetery on May 30, 1868, where both Union and Confederate soldiers are buried.”

One of the first iterations of Memorial Day was called “Decoration Day” because it was a time when family members would decorate the graves of their relatives who died in the war. Several towns and cities across the US claim to have started the tradition.

But then 1996, a remarkable discovery occurred in a dusty Harvard University archive.

David Blight, a professor of American History at Yale University, was researching a book on the Civil War when “he had one of those once-in-a-career eureka moments.” A curator at Harvard’s Houghton Library asked if he wanted to look through two boxes of unsorted material from Union veterans. “There was a file labeled ‘First Decoration Day,’” remembers Blight, still amazed at his good fortune. “And inside on a piece of cardboard was a narrative handwritten by an old veteran, plus a date referencing an article in The New York Tribune. That narrative told the essence of the story that I ended up telling in my book.”

Professor Blight had discovered the earliest recorded Memorial Day commemoration “organized by a group of Black people freed from enslavement less than a month after the Confederacy surrendered in 1865.”

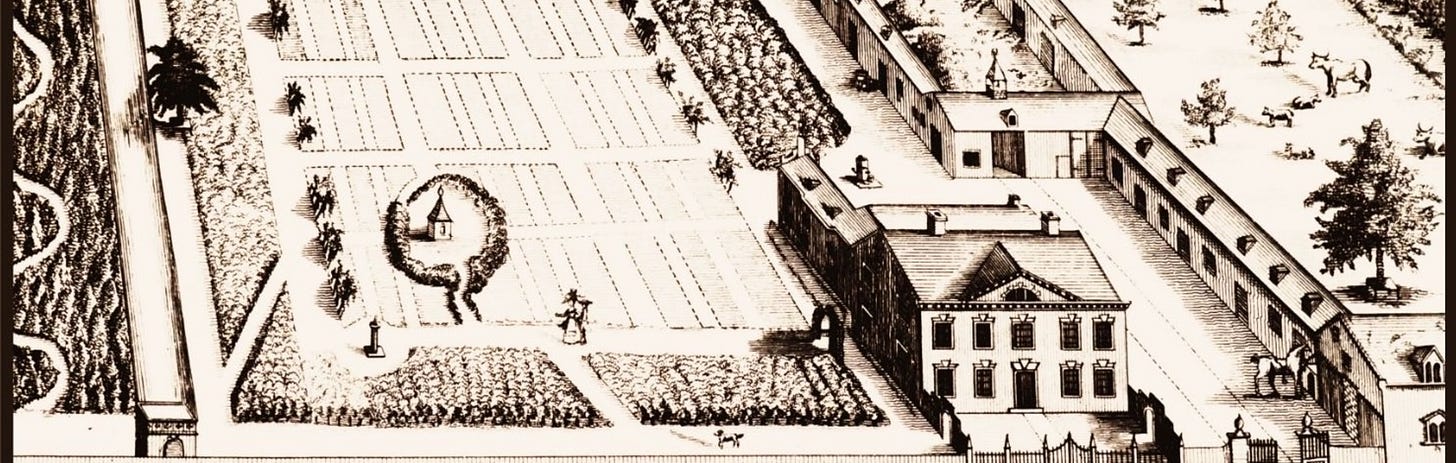

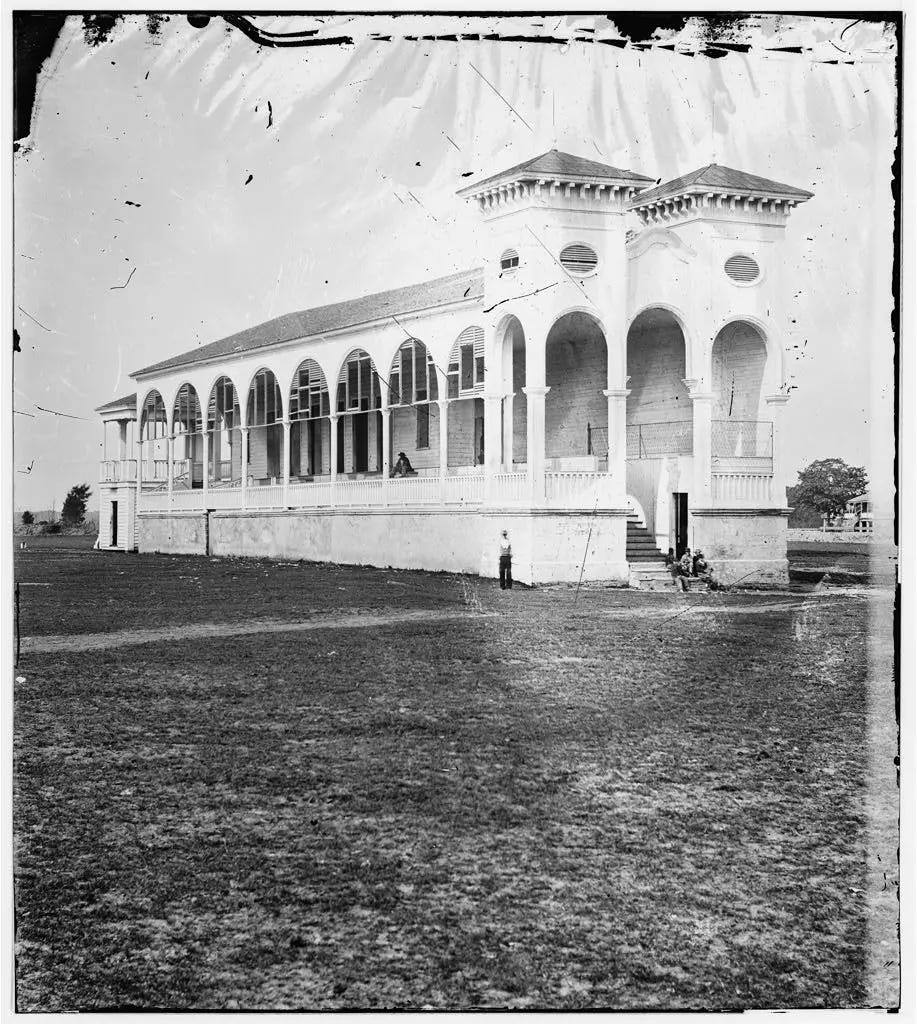

This 1865 commemoration occurred at Charleston’s Washington Race Course and Jockey Club. In the late stages of the Civil War, the Confederate army “transformed the formerly posh country club into a makeshift prison for Union captives.” More than 260 Union soldiers died from disease and exposure while being held in the race track’s open-air infield. Their bodies were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstands.

When Charleston fell to the Union Army and Confederate troops evacuated the badly damaged city, “those freed from enslavement remained.”

The emancipated men and women gave the fallen Union prisoners a proper burial. They “exhumed the mass grave and reinterred the bodies in a new cemetery with a tall whitewashed fence inscribed with the words: ‘Martyrs of the Race Course.’”

Then on May 1, 1865, something even more extraordinary happened. According to two reports that Professor Blight found in The New York Tribune and The Charleston Courier, “a crowd of 10,000 people, mostly freed slaves with some white missionaries, staged a parade around the race track. 3,000 Black schoolchildren carried bouquets of flowers and sang ‘John Brown’s Body.’”

I looked up the “John Brown’s Body” song and immediately recognized it, and I’m sure you will too. To help bring this amazing history alive, here is audio of the song:

Members of the “famed 54th Massachusetts and other Black Union regiments were in attendance and performed double-time marches. Black ministers recited verses from the Bible.”

If the news reports are accurate, the 1865 gathering at the Washington Race Track in Charleston would be the earliest Memorial Day commemoration on record.

After making this discovery, Blight excitedly called the Avery Institute of Afro-American History and Culture at the College of Charleston, looking for more information on the historic event. They were not aware of this historical event and did not have any further information for him.

“This was a story that had really been suppressed both in the local memory and certainly the national memory,” says Blight. “But nobody who had witnessed it could ever have forgotten it.”

Writes Dave Roos: “Once the war was over and Charleston was rebuilt in the 1880s, the city’s white residents likely had little interest in remembering an event held by former enslaved people to celebrate the Union dead. ‘That didn’t fit their version of what the war was all about,’ says Blight.”

Over time, the Washington horse track and country club were torn down, and thanks to a “gift from a wealthy Northern patron,” the Union soldiers' graves were moved from the humble white-fenced graveyard in Charleston to the Beaufort National Cemetery.

The history of this momentous day had been all but forgotten until…

Professor Blight wrote a book Race and Reunion and in 2001, he gave a talk about the history of Memorial Day at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. After the talk was finished, an older Black woman approached him. “You mean that story is true?” the woman asked Blight. “I grew up in Charleston, and my granddaddy used to tell us this story of a parade at the old race track, and we never knew whether to believe him or not. You mean that’s true?”

Writes Roos: “For Blight, it’s less important whether the 1865 commemoration of the ‘Martyrs of the Race Course’ is officially recognized as the first Memorial Day. ‘It’s the fact that this occurred in Charleston at a cemetery site for the Union dead in a city where the Civil war had begun,” says Blight, “and that it was organized and done by African American former slaves is what gives it such poignancy.’”

I’m also adding additional context from an article from the College of Charleston:

Adam Domby, assistant professor of history at the College of Charleston, did additional research in conjunction with Professor Blight’s on the Washington Race Course event. Not surprisingly, “many white southerners who had supported the Confederacy, including a large swath of white Charlestonians, did not feel compelled to spend a day decorating the graves of their former enemies.” Domby is convinced that it was often “African American southerners who perpetuated the holiday in the years immediately following the Civil War.”

Domby writes, “African Americans across the South clearly helped shape the [Memorial Day] ceremony in its early years…Without African Americans the ceremonies would have had far fewer in attendance in many areas, making the holiday less significant.”

After the Civil War, we learned above how Union soldiers’ graves were moved from the “Martyrs of the Race Course” cemetery at the Washington Race Course in Charleston to the Beaufort National Cemetary. Let’s discuss more about the Beaufort National Cemetary below!

Beaufort National Cemetery is a United States National Cemetery located in Beaufort, South Carolina. It is managed by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs and encompasses 44.1 acres, and as of 2024, had over 28,725 interments.

The original interments in the cemetery were men “who died in nearby Union hospitals during the occupation of the area early in the Civil War, mainly in 1861, following the Battle of Port Royal.”

Battlefield casualties from around the area were also reinterred in the cemetery, including over 100 Confederate soldiers.

It became a National Cemetery with the National Cemetery Act by Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

Of the Civil War soldiers buried here, there are: “9,000 Union soldiers (3,607 unknown) 2,800 POWs from the camp at Millen and 1,700 African-American Union soldiers.” There are also 102 confederate soldiers. The remains of 27 Union prisoners of war were reinterred from Blackshear Prison following the war.

Beaufort National Cemetery now has interments from every major American conflict since the Civil War, including the Spanish–American War, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Gulf War.

In 1987, the remains of 19 Union soldiers of the all-black Massachusetts 55th Volunteer Infantry were discovered on Folly Island, South Carolina. The Folly North Archaeological Project (1990) did further excavations in the area after Hurricane Hugo, which revealed artifacts such as “leather shoes, rubberized canvas, wood staves and animal bone.”

The Union Army’s Massachusetts 55th had been stationed on Folly Island from late 1863 to early 1864 and was a sister unit to the better-known Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry, featured in the film Glory (1989), which starred Matthew Broderick, Morgan Freeman, and Denzel Washington.

On May 29, 1989, the 54th soldiers were reinterred in the Beaufort National Cemetery with full military honors. Cast members from the film served as the honor guard at the ceremony. Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis presented the Massachusetts regimental flag to “the color guard as 144 black and white Civil War re-enactors recreated a military burial service in accordance with 1863 Army regulations…The Memorial Day salute for the soldiers was fired by a black Civil War re-enactment group from Boston as a Confederate unit from Georgia stood by.” Governor Dukakis said in his remarks:

Unlike the men and boys who fought and died for a way of life they believed in, and others who did so with equal bravery to establish the sovereignty of the national government, these black soldiers ... fought for their own liberty, to grasp their own freedom and ensure both for others of their own race. Liberty once gained and then neglected is liberty in peril. Oppression once defeated and then forgotten is likely to return. So we do well to gather here today, so close to that place where these brave men, black and white, fought to gain that liberty and suppress that oppression, and died in the effort, as fitting testament to their cherished memory.

Beaufort National Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997.

List of War Memorial Monuments in South Carolina (by Region)

Here is a list of 20 notable veteran and war-related monuments and memorials across South Carolina, organized by region. Each entry includes the name, year erected (when available), and address.

Upstate

Daniel Morgan Monument (1881) – Main & Church Streets, Spartanburg, SC

Confederate Monument (Greenville) (1892) – Confederate Plaza near Springwood Cemetery, Greenville, SC

Anderson County Confederate Monument (1902) – Courthouse Square, Anderson, SC

Cowpens National Battlefield (1929) – 4001 Chesnee Hwy, Gaffney, SC

Kings Mountain National Military Park (1931) – 2625 Park Rd, Blacksburg, SC

Midlands

South Carolina Armed Forces Monument (2005) – 1200 Gervais Street, Columbia, SC

South Carolina Monument to the Confederate Dead (1879) – South Carolina State House Grounds, Columbia, SC

Revolutionary War Generals Monument (1913) – South Carolina State House Grounds, Columbia, SC

Spanish-American War Veterans Monument (1941) – South Carolina State House Grounds, Columbia, SC

African-American History Monument (2001) – South Carolina State House Grounds, Columbia, SC

Lowcountry

The Defenders of Fort Moultrie (Jasper Monument) (1877) – White Point Garden, Charleston, SC

Confederate Defenders of Charleston Monument (1932) – White Point Garden, Charleston, SC

USS Amberjack Memorial (1950s) – White Point Garden, Charleston, SC

H.L. Hunley Monument (1899) – White Point Garden, Charleston, SC

Veterans Memorial at Waterfront Park – Concord Street, Charleston, SC

Pee Dee

Veterans Memorial and Veterans Walk – 100 E Carolina Avenue, Hartsville, SC

Florence Veterans Park (2008) – 601 Woody Jones Blvd, Florence, SC

Darlington Veterans Memorial – Public Square, Darlington, SC

Marlboro County War Memorial – Courthouse Square, Bennettsville, SC

Sumter Veterans Memorial Park – Broad Street & Liberty Street, Sumter, SC

We salute all those who died in the line of service — in defense of the freedoms we hold dear. A Happy Memorial Day to all!

If you voted just “OK” on the newsletter today, I want to hear from you! Reply to this email and send me your feedback. :)

➳ Sources — South Carolina Memorial Day History

"After 126 Years, 19 Black Union Soldiers Receive Military Burial." UPI Archives, 29 May 1989, https://www.upi.com/Archives/1989/05/29/After-126-years-19-black-Union-soldiers-receive-military-burial/7519612417600/. Accessed April 2024.

“Beaufort National Cemetery.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaufort_National_Cemetery. Accessed April 2024.

“100 Years Later, Great War’s Impact on Greenville Still Evident.” Greenville Journal, https://greenvillejournal.com/community/100-years-later-great-wars-impact-greenville-still-evident/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed April 2024.

“Memorial Day Events Across Upstate SC.” Greenville News, 21 May 2025, https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news/local/2025/05/21/memorial-day-event-parades-ceremonies-gatherings-holiday-anderson-greenville-spartanburg-clemson/83671071007/. Accessed April 2024.

“Memorial Day History.” College of Charleston Today, 29 May 2017, https://today.cofc.edu/2017/05/29/memorial-day-history/. Accessed April 2024.

“Memorial Day History.” College of Charleston Today, 29 May 2017, https://today.cofc.edu/2017/05/29/memorial-day-history/. Accessed April 2024.

Roos, Dave. “The Overlooked Black History of Memorial Day.” History.com, 22 May 2023, https://www.history.com/news/memorial-day-civil-war-slavery-charleston. Accessed April 2024.

“On Hallowed Ground: The Beaufort National Cemetery.” Explore Beaufort SC, https://explorebeaufortsc.com/on-hallowed-ground-the-beaufort-national-cemetery/. Accessed April 2024.