#78: The Great Wagon Road, The Jenkins Orphanage Band, and the Rice Kings

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #78 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

tnpruitt56

dmanninginfay

johnsettle

byumom

nanapameast

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, May 4th at 1:00 pm | “Lecture by David Henry Lucas: The Rice Kings” | Horry County Museum, McCown Auditorium | Conway, SC | FREE Admission

“The Horry County Museum presents a lecture and book signing by David Henry Lucas on his series The Rice Kings on Saturday, May 4, at 1:00 PM. The series chronicles the history of the Lucas family over 300 years, starting with Jonathan Lucas in 1754. Books will also be available to purchase after the program.

…Having written a book chronicling the history of his US Supreme Court fight to protect private property rights in the 90’s, Mr. Lucas decided to embark on a new profession. In 2012, he began work on a memoir relating the story of his time as a student athlete at the University of South Carolina.

As a follow-up project, he has taken on the challenge of romanticizing the history of his forbears, starting in the year 1754. The first novel is entitled “The Rice Kings, Book One, The Beginning” which chronicles the early life and training of Jonathan Lucas, a fourth great grandfather. “The Rice Kings, Book Two. Charleston,” brings the story to America where Jonathan invented the rice mill. This invention allowed the South Carolina Lowcountry to become incredibly wealthy and produced a golden era for the region. These two books are the first in a series of historical novels that are intended to relate the saga of the rise and fall of the Old South. Time permitting; the series will describe the aftermath of the War Between the States through the eyes of the people who experienced it. Finally, the story of the slow economic recovery of the South, beginning with the life of his grandfather, H. S. Lucas, born in 1888, and expanding the history of the Lucas Family throughout the 20th Century.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

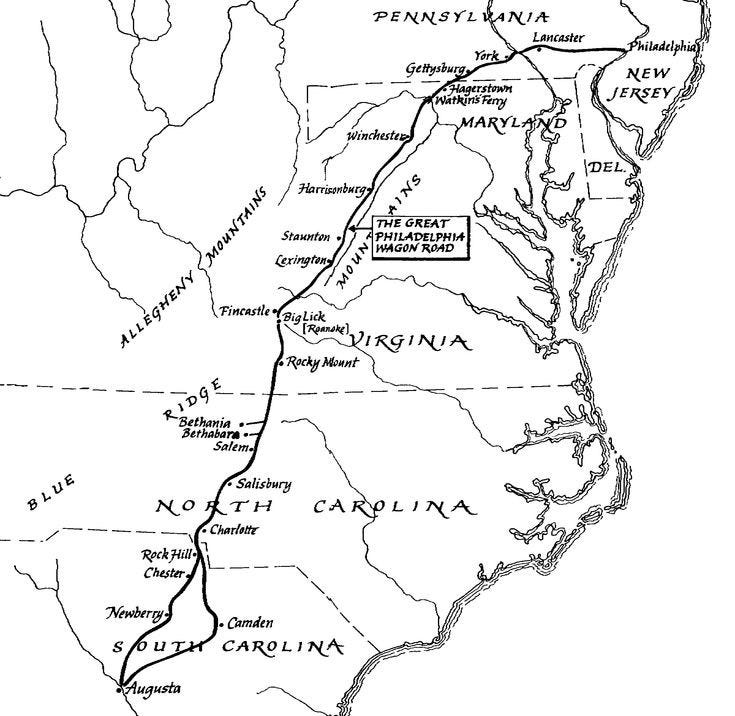

Did you know that the Great Wagon Road that connected Philadelphia to Georgia (and went through SC) was one of the most highly trafficked roads in early America?

The Great Wagon Road — also known as the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road — was an 800-mile route developed from a series of Native American trails. It became a migration route for German, Scots-Irish, Welsh, English, and Swiss settlers to migrate to the southern states “seeking cheap land” on which to settle.

The route took people through the Great Appalachian Valley from Pennsylvania to North Carolina, then through South Carolina to Georgia.

Immigrants came by foot, horse, or wagon.

In good weather, a horseman could go about 20 miles a day. A wagon averaged half that distance.

The wagons used were the iconic Conestoga wagons, which originated in Pennsylvania during the first half of the 1700s and were built to carry 2-3 tons. The wagons were meant to be pulled by a team of 4-6 horses or oxen. The average dimensions of the Conestoga were 22 feet (length), 5 feet (width), and 12 feet (height).

The Conestoga wagon was so versatile that it was also used in the American westward expansion of the mid-late 19th century. (Shout out to those of us who played the Oregon Trail computer game!)

The trail was initially so narrow that it was only passable by travelers on horseback. Traffic on the road increased after 1744, then “reduced to a trickle” during the French & Indian War from 1756-1763, but after the way, it was said “to be the most heavily travelled main road in America.”

Settlers worked to widen the road and make it more passage by cutting trees, finding suitable fords across rivers, and working around other obstacles.

By 1765, the trail had been widened and improved enough to allow the passage of horse-drawn vehicles like the Conestoga Wagon.

An independent group called Piedmont Trails has identified some of the modern-day roads that are the remnants of the Great Wagon Road in South Carolina:

“The road follows South Carolina Highway 23 for 21 miles to the Edgefield County line. A man named Francis Higgins operated a ferry on the Saluda River and was well-known to many travelers along the road. At this point, the road follows South Carolina Highway 121 for approximate 30 miles until the Savannah River. The travelers would navigate the river to reach Augusta, Georgia.”

The South Carolina Encyclopedia sums up the significance of the Great Wagon Road in South Carolina history:

“This southern movement of thousands of settlers rapidly populated the Carolina backcountry and gave it a unique Scots-Irish and German flavor. In the closing decades of the colonial era, the Great Wagon Road was among the most heavily traveled in British North America, making it one of the most important frontier movement trails in United States history.”

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you know that the famous Charleston dance had its origins in African / Gullah Geechee culture and was made popular by an orphan band?

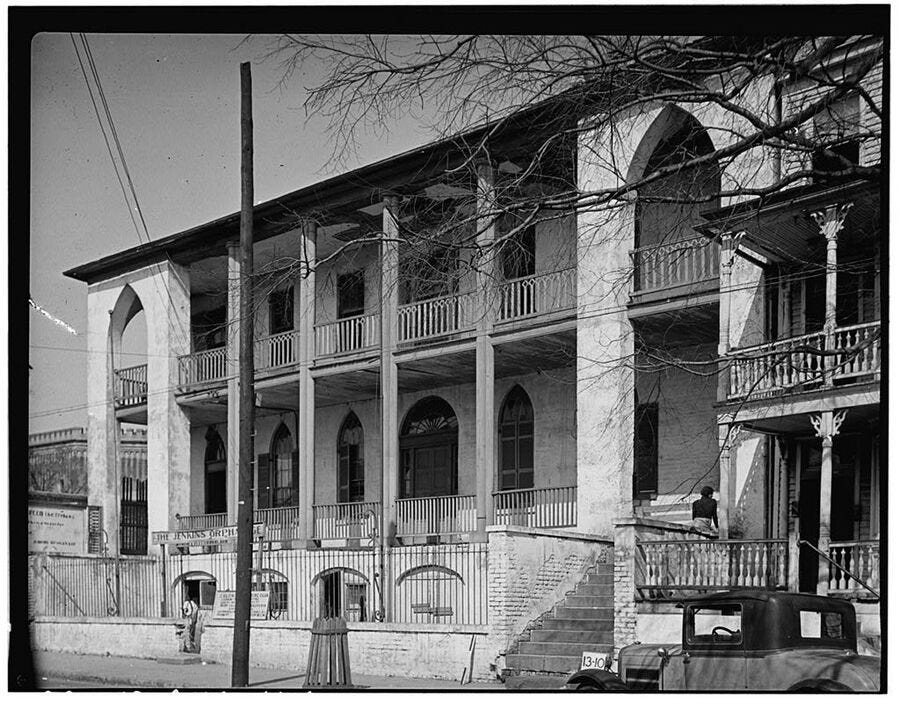

Founded by the Reverend Daniel Jenkins, a former orphan himself, the Jenkins Orphanage opened in 1891 in Charleston “next to the old jail.”

The original site of the orphanage was on 660 King Street. In 1893, the orphanage moved to the Old Marine Hospital at 20 Franklin Street. This National Historic Landmark was designed by “America’s first architect,” Robert Mills, and served as the home of the orphanage until 1937.

The orphanage began receiving “scores of neglected children” almost as soon as it opened its doors.

While South Carolina had 9 orphanages for white children at the time, Jenkins was the sole refuge for African-American orphaned children in the state.

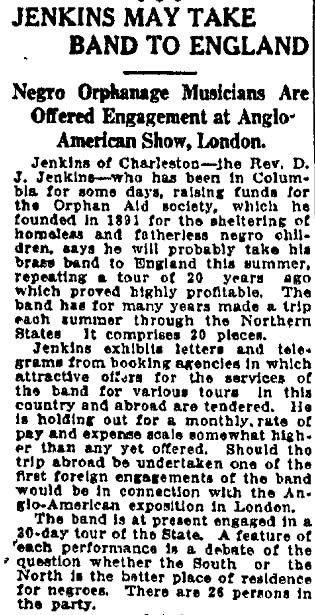

While Jenkins was not a musician himself, he conceived of a brilliant idea to organize his young orphans into a band that would not only give the students a creative outlet, but would also provide a means of raising badly needed funds for the orphanage’s operations.

As Time Magazine explained in 1935, "Having on his hands a number of undernourished, rickety and tuberculous youngsters, Jenkins optimistically decided 'My children's lungs would get strong by blowing wind instruments.'"

Jenkins put out a request to Charlestonians for old instruments, wrangled some cast-off uniforms from the Citadel, and found a pair of local musicians — P.M. "Hatsie" Logan and Francis Eugene Mikell — to teach the children to play.

The children learned quickly and trained several hours a day in addition to their other tasks and chores.

At first, they played mainly on street corners, literally "passing the hat." However, as their reputation grew, so did their opportunities.

In just 2 short years, the Jenkins Orphanage Band began touring the US and abroad.

In 1905, the Jenkins Orphanage Band was invited to play for President Roosevelt's inauguration, and in 1909 they repeated this honor for President Taft.

The band occupied their own stage at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904, and in 1914, they were given free passage to London (plus new uniforms!) to play at the Anglo-American Exposition.

Over the years, the band travelled to Austria, England, France, Germany, and Italy.

The band even performed on Broadway for the entire original run of DuBose Heyward's Porgy and Bess. Heyward “insisted on importing the music [of Charleston] itself. From 1927 until the show closed to tour in 1928, the number one Jenkins Orphanage Band played every night in the stage performance of the play. Many of the players remember the New York episode as one of the most exciting times in the band’s history.”

To further increase revenues, Jenkins had up to 5 bands tour each summer and 2 each winter.

By the 1920s, the orphanage had become a “go to place” for up-and-coming Charleston musicians “to meet and jam.” Many non-orphans auditioned for the band, and the better ones were allowed to join.

As musician and artist Merton Simpson recalled:

"A lot of good musicians came out of that group, people like Cat Anderson ... [and] ... Freddie Green Basie [sic], these are all alumni of Jenkins. Like I said, it was a home for sort of delinquent boys but everybody wanted to go there just because it was such a good place to get involved with music. Charleston was at that time a kind of musical center for jazz."

It was the various Jenkins bands that spread this "Charleston Sound" up and down the Eastern Seaboard. In those early years, “when musical innovations were still conveyed through live performances rather than records and airwaves, Charleston's young troubadours weren't just earning their keep – they were contributing directly to the budding American jazz scene.”

Not only were they spreading the “Charleson Sound,” but the young orphans also helped make popular the famous “Charleston Dance” which has its origins in African culture brought to America through the slave trade.

Enslaved Africans brought the “Juba dance” from the Kongo to Charleston, and the dance evolved into what would be known as the “Geechie dance” and eventually as “the Charleston.”

Even in the 18th century the Juba dance was so popular that “a premium was placed on black domestics who would be good Juba dancers to teach the lady of the house some steps.”

When the Jenkins Orphanage Band performed, children from the band would perform a “Geechie dance” (referencing the Gullah Geechie culture) in front of the band.

Jazz pianist Willie Smith in the book Steppin On The Blues recalls:

“Some folks say that is how the Charleston got its name. I am a tough man for facts and I say the Geechie dance had been in New York for many years before Brown showed up. The kids from the Jenkins Orphanage Band in Charleston used to do Geechie steps when they were in New York on their yearly tour.”

Around the same time, African American pianist and composer John P. Johnson had watched some Gullah dancers from Charleston do their distinctive Charleston dance at The Jungles Casino in New York City in 1913. Johnson was inspired by the dancers to compose his famous song “The Charleston.”

Author Alphonso Brown in his book A Gullah Guide to Charleston, tells a story that on one of the Jenkins Orphanage Band’s tours to New York, John P. Johnson taught the orphan boys his “Charleston” song, which had been a hit in his African-American Broadway revue show “Runnin’ Wild.” The song became one of the most popular songs of the “Roaring 20s” and was meant to be played while people danced the Charleston.

Here is the “Charleston” song by James P. Johnson:

And here is a video of the Jenkins Orphan Band playing their tunes while a young boy at the front does the Charleston!

In the 1920s, the Charleson dance turned into a “popular American craze” that became a feature of the Jazz Age, flappers, and the era of Prohibition.

In 1925, famous African American performer Josephine Baker introduced the Charleston dance in Europe during her Parisian tour “Le revue negre”. The Charleston dance then became international craze.

Here is a video of Josephine Baker performing the Charleston:

Though the Jenkins Orphanage Band’s popularity remained high for many years, by the 1930s, band revenues began to fade, and “a bank collapse seriously damaged the orphanage's finances even further.”

Nearing the end of his life, Reverend Jenkins reflected on the impact of the orphanage. He told Time Magazine in 1935 that of the thousands of children who had passed through the orphanage since 1891, “fewer than 10 had ever ended up in prison — a fairly remarkable statistic given the dire circumstances into which most of his charges were born.”

Reverend Jenkins died in 1937 and he left behind a lasting legacy. From the South Carolina Encyclopedia:

“Five thousand children had passed through his orphanage or lived on the farm facilities. In 1985 a portrait of Jenkins was hung in the Charleston City Council chambers, the first such honor bestowed on an African American.”

Today, the Jenkins Orphanage is now the Jenkins Institute and is located in North Charleston. It cares for “about 20 children, all girls between the ages of 11 and 21.”

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“The chronicle of the Wagon Road is the chronicle of infant America, from 1607 until the age of the railway. It’s the story of achievement against great odds. Breaking with the European traditions that they brought with them to America, the diverse settlers along the Wagon Road began to create the new American society, which changed the 19th-century history of the world.”

—Excerpt from author Parke Rouse Jr. in his 1973 book, The Great Wagon Road

The Great Wagon Road article sources:

“The Great Wagon Road of the East.” Legends of America – Traveling through American History, https://www.legendsofamerica.com/great-wagon-road/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

“The Great Wagon Road.” Carolana, https://www.carolana.com/SC/Royal_Colony/

the_great_wagon_road.html. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.“Mapping the Great Wagon Road.” NCpedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/

mapping-great-wagon-road. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.“The Great Wagon Road Enters Into South Carolina – Piedmont Trails.” Piedmont Trails, 28 Jan. 2019, https://piedmonttrails.com/2019/01/27/the-great-wagon-road-enters-into-south-carolina-2/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

Smith, W. Calvin. “Great Wagon Road.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/great-wagon-road/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

Charleston Dance article sources:

Hutchisson, James. “Our History.” https://www.jenkinsinstitute.org/index.php/our-history. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

“Jenkins Orphanage Band.” SCIWAY, https://www.sciway.net/south-carolina/jenkins-orphanage.html. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

“The History Of The Charleston Dance.” Ksenia’s Secrets of Solo, 23 Aug. 2020, https://secretsofsolo.com/2020/08/the-history-of-the-charleston-dance/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

“Jenkins Orphanage and Jenkins Orphanage Band” Discovering Our Past: College of Charleston Histories, https://discovering.cofc.edu/items/show/25#:~:text=The%20Jenkins%20Orphanage%20Band%2C%20wearing,toured%20simultaneously%20during%20the%201920s. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

“Tracing the Roots of the ‘Charleston’ Dance.” Charleston County Public Library, 17 July 2020, https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/tracing-roots-charleston-dance. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

“The Jenkins Orphanage Band.” TempoSenzaTempo, https://temposenzatempo.blogspot.com/2014/08/the-jenkins-orphanage-band.html. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

West, Donald. “Jenkins, Daniel Joseph.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/jenkins-daniel-joseph/. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!