#82: Septima Poinsette Clark, Creation of SC State Parks, and a lecture on the History of Dorchester County

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #82 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

sceiron51

edwardgermano7

cre51

john.mojonnier

awwelchel

cmhonnen19

hedens

kert@jhhiers.com

carladwhitlock@yahoo.com

mrspenn13@gmail.com

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Thursday, May 9th from 7:00 - 8:00 pm | “Newly Published book: The History of Dorchester County, South Carolina” | Greater Summerville/Dorchester County Chamber of Commerce | Summerville, SC | FREE event

“Step back in time and immerse yourself in the rich tapestry of Dorchester County's history with the latest release, "The History of Dorchester County, South Carolina."

Delve into the captivating narratives meticulously curated by the Dorchester County Historical Society, chartered in 2004 by a passionate collective driven to preserve the essence of our past.

This compelling book is the culmination of their unwavering dedication to researching and documenting the vivid stories that define our community. Join us and hear firsthand from Phyllis Hughes, the president of the organization, as she shares insights into the fascinating journey behind the creation of this invaluable resource.

Come, discover the heart and soul of Dorchester County through the pages of this newest release.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

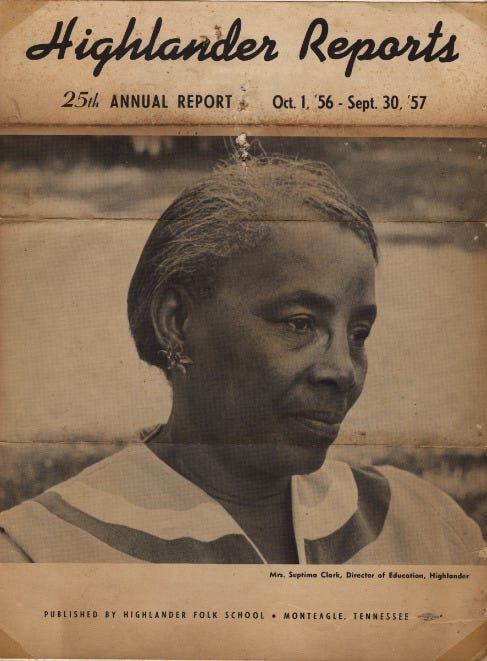

Septima Poinsette Clark

Septima Poinsette Clark was born in Charleston in 1898.

Her mother, Victoria Warren Anderson Poinsette was a launderer and her father Peter Poinsette had been born a slave at the plantation of the famous South Carolinian statesman Joel Roberts Poinsett.

(Note from Kate: while I could not find any direct sources to confirm this, knowing that many slaves took/were given their owner’s last names, I am assuming that Peter Poinsette’s name (with the added “e”) is taken from his former owner. And the name became Septima’s middle name.)

Septima grew up in Charleston in the Reconstruction Era when the city was divided by race and class.

She attended the prestigious Avery Normal Institute for African Americans and graduated in 1916.

When she was 18, Clark started her career as a schoolteacher at a black school on Johns Island, just outside of Charleston.

Due to the color of her skin, Septima was not allowed to teach in the Charleston public school system, and instead she had to accept teaching positions in rural school districts.

Septima and her colleagues worked together and protested to win African Americans the right to teach at Charleston public schools. The campaign was successful and Septima was convinced that social activism had the power to better the lives of African Americans.

Septima was eager to do more to advance the rights of African Americans and she joined the Charleston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1929, Septima moved to Columbia and taught high school there. While in Columbia, she participated in a class action lawsuit filed by the NAACP that led to pay equity for Black and white teachers in South Carolina.

In the 1950s, Septima and the NAACP advocated for the integration of public schools. The Charleston City School Board took notice of her involvement in NAACP initiatives, and she was asked to keep her membership a secret, but she refused. As a result, the school board fired her. No longer employed, Septima devoted all of her time to activism.

Clark regarded her activism as an extension of her Christian faith. As she stated in a 1964 essay, “Where there is obedience to the gospel, there will be concern for the less fortunate. . . The Christian can never be content with token progress by a fortunate few.”

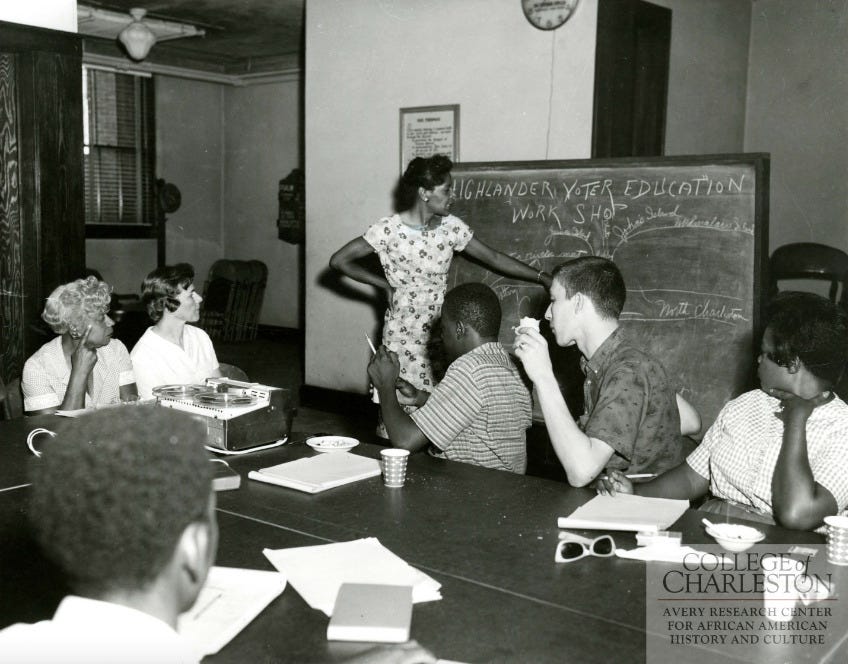

Septima soon focused on the inequality of the voting system in the South. Black men and women had the right to vote, but were often kept from the voting polls by literacy tests. Many adult African Americans could not read because their parents and grandparents were formerly enslaved. Slavery was legal in the United States until 1865, and it was illegal to teach an enslaved person to read and write. As a result, literacy tests prevented many black citizens from voting, even in the 1950s and 1960s.

Septima dedicated herself to designing educational programs to teach African American community members how to read and write, and thus have the right to vote.

She was hired by the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, where she served as the director of workshops and taught literacy courses. These classes were very progressive at the time as they were “integrated” with both white and Black citizens attended the workshops and learning together.

Septima developed the curriculum for “Citizenship Education Workshops” that included both literacy and citizenship rights.

Rosa Parks participated in one of Septima’s workshops just months before she helped launch the Montgomery bus boycott.

The workshops spread across the South. When the Highlander School unfortunately closed in 1961, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) established the Citizenship Education Program (CEP), which was modeled on Clark’s citizenship workshops.

Martin Luther King Jr. was the first SCLC president.

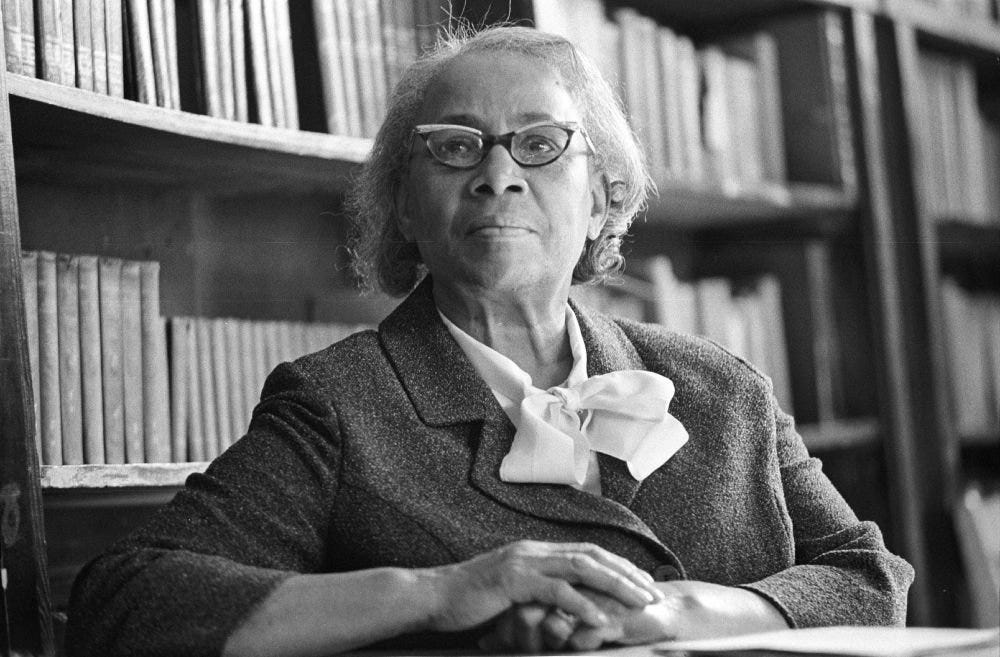

Clark became the SCLC's director of education and teaching — and was the first woman to hold a position on their board.

Her idea for “Citizen Education” and “Citizenship Schools” became the cornerstone of the Civil Right Movement.

Between 1957 and 1970, more than 28,000 southern African Americans passed through these schools. Connecting grassroots education to grassroots activism, the program played a crucial role in galvanizing people to participate in the civil rights movement.

Clark continued to work with Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to win rights for African Americans.

Martin Luther King, Jr., commonly referred to Septima Poinsette Clark, as “The Mother of the Movement.”

Although deeply involved in the cause, Septima would struggle against sexism during her time on the SCLC. She claimed that women being treated unequally was "one of the greatest weaknesses of the civil rights movement.”

Septima Clark continued to serve as an advocate and a leader until her death in 1987.

In 1972, Septima won election to the Charleston County School Board, becoming both its first female and first African American member.

She also served on the local Advisory Council on Aging and worked with city clubwomen to establish a day care center.

In 1976, she received a Race Relations Award from the National Education Association.

Septima also spent decades working in black women’s organizations, such as the YWCA, to mentor black girls and improve the quality of life for black South Carolinians.

In 1978, Clark was awarded an honorary doctorate of humane letters by the College of Charleston.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter awarded Septima Poinsette Clark a Living Legacy Award.

In 1987, her second autobiography, Ready from Within: Septima Clark and the Civil Rights Movement (Wild Trees Press, 1986) won the American Book Award

Patricia Williams Dockery is a playwright who recently wrote a play on Septima Poinsette Clark’s life. She was recently quoted in an article for Channel 2 News in Charleston:

“It cannot be understated because her work, her blueprint really turned the tide and her work is directly responsible for — by the time the Voting Rights Act passed — close to a million southern Blacks who had never voted before were not only registered, but voting, and so we owe that to her.”

The director of Patricia Williams Dockery’s play, Sharon Graci, was also recently quoted in the same article:

“Septima Clark’s impact is felt today. There are so many African-American politicians, especially through the eighties and the nineties, who really had their roots tied into the citizenship schools where we really see huge social movements and so much progress based on what Septima Clark did. I’m hoping that there’s just a much greater appreciation for who she was and that we are really proudly and broadly claiming her not only as a Charlestonian but just a great American woman who deserves to be broadly known.”

Septima Poinsette Clark was inducted into the Soth Carolina Hall of Fame in 2014. Here is a short video about her life from ETV:

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Creation of SC State Parks

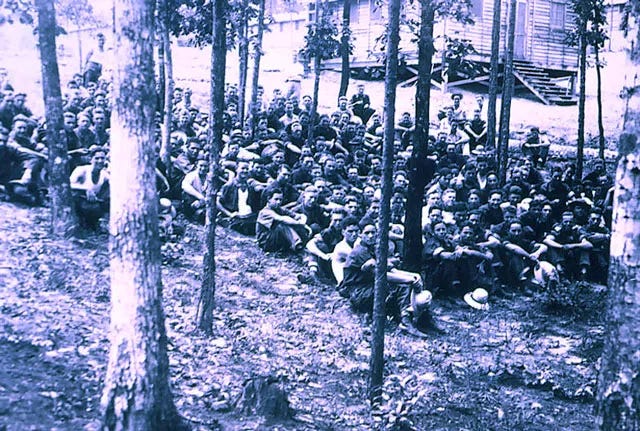

During the darkest days of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) with a mission to put young men to work saving America’s natural heritage.

South Carolina embraced the program early, mostly for its economic benefits, and a number of CCC camps were set up around the state.

Initial mobilization and management of the CCC fell to the military, but soon leadership and planning roles came to professionals in the National Park Service with “training in resource management, landscape architecture, forestry, and recreation planning.”

Many conservationists, such as Ben S. Meeks of Florence, also assumed leadership roles and instilled a conservation philosophy to the movement.

Between 1933 and 1942 South Carolina’s CCC camps employed more than 49,000 workers, many between the ages of 18-25.

In countless hours of backbreaking and often tedious work, CCC workers “fought soil erosion and wildfires, created a state parks system, built roads and trails, erected fire towers, and carried out extensive reforestation projects. Wages sent home by CCC workers helped many families weather the Great Depression.”

In South Carolina, initially the CCC created 16 state parks that preserve some of the state’s most beautiful places. This work provided access to thousands of acres of public land to all South Carolinians. It also gave jobs to the unemployed and helped many families survive hard times.

A combination of local initiative and federal involvement led to many of our first state parks.

Park sites were often donated by local entities, added to, and developed as recreation demonstration units under the guidance of the National Park Service.

Cheraw was the first of these, in 1934, where the community purchased 706 acres for a state park, the first property in the system. That same year, the legislature charged the Commission of Forestry (the only agency with a mandate to conserve natural resources) with the responsibility of developing and administering a state park system.

Using local building materials, such as stone and rough-cut timbers, the men of the CCC and other federal projects built lasting structures that we still enjoy today at Oconee, Paris Mountain, Table Rock, Kings Mountain, and several other parks.

The Civilian Conservation Corps developed the following state parks in South Carolina: Aiken, Barnwell, Cheraw, Chester, Colleton, Edisto Beach, Givhans Ferry, Hunting Island, Lake Greenwood, Lee, Myrtle Beach, Oconee, Paris Mountain (Listed on the National Register of Historic Places), Poinsett, Sesquicentennial, Table Rock (listed on the National Register of Historic Places).

One of the CCC’s most notable accomplishments was its rustic-style architectural legacy. As a national style, rustic architecture developed in resort and park settings during the early twentieth century. It combined naturalistic “landscape design and elements of the Shingle, Adirondack Great Camp, Prairie, and Craftsman architectural styles.” By relying heavily on local materials such as stone and hand-hewn logs, rustic-style buildings appeared as though they had “been constructed by frontier craftsmen using only primitive hand tools in harmony with natural surroundings and local building traditions.”

CCC rustic landscaping emphasized “use of native plant species, curvilinear roads and paths, and the creation of romantic settings that encouraged outdoor recreation and exploration of nature.”

Perhaps the CCC’s most important legacy was the role it played in the transformation of South Carolina’s rural landscape. By the 1930s intensive cotton farming and logging had left much of the state’s land devastated “by deforestation, fires, gullies, and sheet erosion.” The CCC began the process of land restoration by building hundreds of miles of terraces and “planting more than 56 million tree seedlings.” The state’s extensive forests of today can be traced back to the pioneering conservation efforts and the visionary planning of the CCC.

The state parks faced another challenge in 1989 when South Carolina received a direct hit from Hurricane Hugo, which closed 16 state parks for varying periods of time. The hurricane hit the South Carolina coast from Folly Beach to Myrtle Beach and continued inland up the Cooper, Santee, Wateree, and Catawba basin. Hugo caused approximately $4.5 million in damage at state parks, primarily to replace or repair equipment and facilities and to clean up debris.

Today there are 47 SC state parks. There is also a fun program where if you visit all of SC’s state parks, you can become an “Ultimate Insider.” Are you an Ultimate Insider?

The State Park Service continues to adapt to meet “recreational trends and economic realities,” as well as to enhance its ability to act as “steward and interpreter of the considerable cultural, historic and natural resources in the 80,000 acres under its management.”

Programs such as Discover Carolina bring more than 25,000 school children a year to SC’s parks.

The State Park System also is actively helping to grow public understanding and appreciation of South Carolina’s major role in the Revolutionary War. One of the parks system’s most recent additions is Musgrove Mill State Historic Site, commemorating and interpreting a pivotal 1780 battle. The park opened in 2003.

From the SC Encyclopedia:

“Though the work of the CCC occurred more than 80 years ago, an important legacy remains. The park planners of the 1930s wanted to create opportunities for all people, rich or poor, to get closer to nature. They believed that outdoor recreation could help cure many of society’s ills, and that nature could inspire, educate and even give meaning to life. Countless South Carolinians have benefited from the CCC’s idealistic vision.”

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“I welcome the opportunity to extend, through the medium of the columns of Happy Days, a greeting to the men who constitute the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Congratulations are due those responsible for the successful accomplishment of the gigantic task of creating the camps, arranging for the enlistments and launching the greatest peacetime movement this country has ever seen.

It is my belief that what is being accomplished will conserve our natural resources, create future national wealth and prove of moral and spiritual value not only to those of you who are taking part, but to the rest of the country as well.

You young men who are enrolled in this work are to be congratulated as well. It is my honest conviction that what you are doing in the way of constructive service will bring to you, personally and individually, returns the value of which it is difficult to estimate. Physically fit, as demonstrated by the examinations you took before entering the camps, the clean life and hard work in which you are engaged cannot fail to help your physical condition and you should emerge from this experience strong and rugged and ready for a reentrance into the ranks of industry, better equipped than before. Opportunities for employment in work for which individually you are best suited are increasing daily and you should emerge from this experience splendidly equipped for the competitive fields of endeavor which always mark the industrial life of America.

I want to congratulate you on the opportunity you have and to express to you my appreciation for the hearty cooperation which you have given this movement which is so vital a step in the Nation's fight against the depression and to wish you all a pleasant, wholesome and constructively helpful stay in the woods.”

—Greeting to the Civilian Conservation Corps by Franklin D. Roosevelt — July 08, 1933

Septima Poinsette Clark article sources:

“Leadership : Septima Clark’s Faith Helps Change the Lowcountry, 1954-1964 | Discovering Our Past: College of Charleston Histories.” Discovering Our Past: College of Charleston Histories, https://discovering.cofc.edu/items/show/63. Accessed 1 May 2024.

“Local and National Leader: Septima P. Clark.” Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/septima_clark/local-and-national-leader. Accessed 1 May 2024.

Lobo, Kristina. “The Mother of the Movement: Septima Clark.” WCBD News 2, WCBD News 2, 25 Feb. 2024, https://www.counton2.com/black-history-month/the-mother-of-the-movement-septima-clark/. Accessed 1 May 2024.

“Septima Clark | SC Hall of Fame.” South Carolina ETV, https://www.scetv.org/stories/2020/septima-clark-sc-hall-fame#:~:text=Septima%20Poinsette%20Clark%20was%20known,greatly%20influenced%20by%20%E2%80%9Creconstruction%E2%80%9D. Accessed 1 May 2024.

“Septima Poinsette Clark.” U.S. National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/septimapoinsetteclark.htm. Accessed 1 May 2024.

CCC Parks article source:

“Civilian Conservation Corps History.” South Carolina Parks | South Carolina Parks Official Site, https://southcarolinaparks.com/education-and-history/ccc-history. Accessed 1 May 2024.

Hester, Al. “Civilian Conservation Corps” South Carolina Encyclopedia, 15 April 2016, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/civilian-conservation-corps/. Accessed 1 May 2024.

“History of State Parks in South Carolina | SCPRT.” South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation & Tourism | SCPRT, https://www.scprt.com/parks/park-service-history#:~:text=Sixteen%20state%20parks%20were%20acquired,for%20completing%20the%20park%20projects. Accessed 1 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!

Wow! I've always heard Septima's name but never knew what a HUGE roll she played! This was very interesting!