#49: Porgy & Bess, early Charleston silversmiths, and a lecture on the Waccamaw Indian People

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #49 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

I’d also like to welcome some new subscribers below!

sbazen2021

kellers

698kelley

will.senn4

zcacooksey

ruthiemaries5

amycstrickland77

haley.d.murray

mcgandy

uelhjones

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, April 6, 2024 | “Waccamaw Indian People” | Horry County Museum | Conway, SC | FREE & Open to the public

“The Horry County Museum presents a lecture by Chief Harold Hatcher on the Waccamaw Indian People on Saturday, April 6, at 1 p.m. This presentation will focus on the history of the Waccamaw Indian People from ancient times to today, including their presence around the time of the Revolutionary War and in the Dimery Settlement.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Did you know that Charlestonian DuBose Heyward started the Poetry Society of South Carolina and wrote the famous opera Porgy and Bess (an adaptation of his own original novel) with George and Ira Gershwin?

Dubose Heyward was born in 1885 in Charleston, South Carolina. His parents were Jane Screven (DuBose) and Edwin Watkins Heyward. He was a descendant of Judge Thomas Heyward, Jr., a South Carolinian signer of the United States Declaration of Independence, and member of the planter elite. Both of Heyward’s parents were “dispossessed aristocrats from the upstate” who had come to Charleston to find new opportunities and better their lives.

Heyward’s family joined the “once powerful families in Charleston that had been reduced to genteel poverty by the Civil War.” Heyward’s father “Ned” Heyward made a meager living working in a rice mill then died in a tragic industrial accident when DuBose was 3 years old. Widowed and without many resources, Dubose’s mother Janie took to sewing, ran a boardinghouse on Sullivan’s Island, and wrote down Gullah folktales she had heard as a little girl and performed them for local arts groups. As a young child, Dubose became immersed in the Gullah world and it wove its way into his imagination.

As much as his dreams flourished in his mind, Heyward’s physical body was frail. He had a series of illnesses, the most serious of which was polio, which he contracted when he was 18. The disease left him “weakened and directionless.” Two years later he contracted typhoid fever, and the following year, fell ill with pleurisy.

Dubose never finished high school. He described himself as "a miserable student" but had a lifelong and serious interest in literature. Without a college education, he took the “only honorable route open to him,” and went into the insurance business with a partner. The agency was successful, and once Heyward solidified his financial base, he gave more time to his first love, writing.

In 1913 Heyward wrote a one-act play, An Artistic Triumph, which was produced in a local theater. Although described as a “derivative work” that reportedly showed little promise, Heyward was encouraged enough to pursue a literary career. In 1917, while convalescing, he began to work seriously at fiction and poetry. In 1918 he published his first short story, "The Brute," in Pagan, a Magazine for Eudaemonists.

The next year, he met Hervey Allen, who was teaching at the nearby Porter Military Academy. They became close friends and in 1920, formed the Poetry Society of South Carolina, which is still in existence today. The Society helped spark a revival of southern literature. Heyward edited the society's yearbooks until 1924 and contributed much of their content. His poetry was well received, earning him a "Contemporary Verse" award in 1921. In 1922 he and Allen jointly published a collection, Carolina Chansons: Legends of the Low Country. They also jointly edited an issue of Poetry magazine featuring Southern writers.

Having met such literary luminaries as Carl Sandburg and Amy Lowell, Heyward gained entry to the New Hampshire artists’ retreat, the MacDowell Colony, where he met his future wife, Dorothy Hartzell Kuhns, a playwright. Shortly after their wedding in New York on September 22, 1923, Dorothy convinced Heyward to set aside his insurance business for full-time writing.

With his wife’s support, and his knowledge of Gullah culture, Heyward “threw caution aside” and wrote Porgy (1925), a novel about African American life in Charleston. The novel tells the story of Porgy, a “crippled street beggar” living in the black tenements of Charleston, South Carolina, in the 1920s. The character was based on a real-life Charlestonian named Samuel Smalls. Known as “Goat Cart Sam,” Smalls’ main mode of transportation was a cart pulled by a goat. By the 1920s, he and his goat cart were familiar figures on Charleston’s downtown streets. There may have been a real life “Bess,” as the real life Porgy was reportedly a ladies’ man. He also enjoyed gambling at places like the Bull Pen, where he’d spend many hours shooting craps, with his goat waiting patiently outside.

Porgy was revolutionary for its time, and “changed literary depictions of blacks in the United States forever” because in this case, a white southerner presented African Americans in an “honest and realistic way,” as opposed to the stereotyped portrayals found in minstrelsy and antebellum narratives. In some of the novel's passages, black characters speak in Gullah, a creole language that developed among enslaved African Americans during the era of slavery on the Sea Islands.

Describing Heyward's achievement in Porgy, the African-American poet and playwright Langston Hughes said Heyward was one who saw "with his white eyes, wonderful, poetic qualities in the inhabitants of Catfish Row that makes them come alive.” Heyward's biographer James M. Hutchisson characterized Porgy as "the first major southern novel to portray Blacks without condescension.”

Heyward was “mildly ostracized from some quarters of Charleston society” for Porgy, but he managed the criticism with grace and self-deprecating humor. By then, Heyward was enthralled with the New York literary world, who celebrated him for his courage in writing Porgy. The artists of the Harlem Renaissance “feted him,” and with his wife Dorothy’s considerable assistance in stagecraft, they worked together to bring a nonmusical version of Porgy to the theater. In the process, they created important dramatic roles for African American actors and raised public awareness of their talents. The play forever ended the “vaudevillian character” of most African American stage works at the time and catapulted Heyward on a trajectory that was to take him up to “the highest literary levels.”

While working on the stage adaptation of Porgy, Heyward was approached by the well-known American composer George Gershwin, who proposed collaborating on an opera of the material. The opera would be called Porgy and Bess. Both Heyward and Ira Gershwin, the composer's brother and regular partner, worked on the lyrics. While composing the opera, George Gershwin researched he play’s subject matter by traveling to Charleston with DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, who took him to various churches and plantations to “get the true flavor and character of the singing” in that part of the South.

Porgy and Bess opened at the Alvin Theatre in New York City on October 10th, 1935, and featured top African-American singers. Large sections of dialogue from the play were set to music for the recitatives in the opera. Here is some footage from opening night.

In the aftermath of its opening on Broadway, Porgy and Bess was, in this first iteration, a critical and financial failure. Audiences were both excited and confused. Was this work by DuBose Heyward and George and Ira Gershwin an opera or a musical, a serious work or a patronizing minstrel show? Deeply divided critics asked similar questions. Porgy and Bess closed after only a few months. From a commercial perspective, this initial production was a flop. Today, however, Porgy and Bess has since had numerous successful revivals, toured Europe, North America, and other continents, and been recognized as an American operatic masterpiece.

As it became clear that Porgy and Bess was not a Broadway success (at first), Heyward made a “hasty retreat away from New York” and back to Charleston. Charleston welcomed him home, “but largely as a prodigal son.” He spent his remaining years fostering local South Carolina playwriting talent as resident dramatist of the Dock Street Theatre, newly restored in 1937. Porgy and Bess, Heyward’s most famous work, was not performed in Charleston until the South Carolina Tricentennial in June 1970.

When the opera came out, Heyward did not get as much credit as he deserved for his lyrical work on Porgy & Bess. In his introduction to the section on DuBose Heyward in Invisible Giants: Fifty Americans Who Shaped the Nation But Missed the History Books (2003), Broadway “giant” and composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim wrote:

DuBose Heyward has gone largely unrecognized as the author of the finest set of lyrics in the history of the American musical theater – namely, those of 'Porgy and Bess'. There are two reasons for this, and they are connected. First, he was primarily a poet and novelist, and his only song lyrics were those that he wrote for Porgy. Second, some of them were written in collaboration with Ira Gershwin, a full-time lyricist, whose reputation in the musical theater was firmly established before the opera was written. But most of the lyrics in Porgy – and all of the distinguished ones – are by Heyward. I admire his theater songs for their deeply felt poetic style and their insight into character. It's a pity he didn't write any others. His work is sung, but he is unsung.

Heyward died on June 16, 1940, in North Carolina and was buried in St. Philip’s Churchyard, Charleston. He was posthumously inducted into the South Carolina Academy of Authors in 1987.

Enjoy this beautiful rendition of “Summertime” from Porgy & Bess:

II.

Did you know that Louis and Heloise Boudo were among Charleston’s best-known and most successful antebellum silversmiths and jewelers?

Louis Boudo arrived in Charleston from Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic about 1809. He established himself as “goldsmith, jeweler and hairworker” (as in hairwork jewelry) in a brief partnership with Nicholas Maurer before opening his own shop on the corner of Church and Queen Streets. At his shop, Boudo marketed himself as a jeweler and watchmaker, and advertised the manufacture of silver spoons and other silver work. In 1811 Louis Boudo married Heloise (Louise) Simonet, the daughter of Eugenie Magniant and Stephen Simonet of Charleston. The couple had 3 children together.

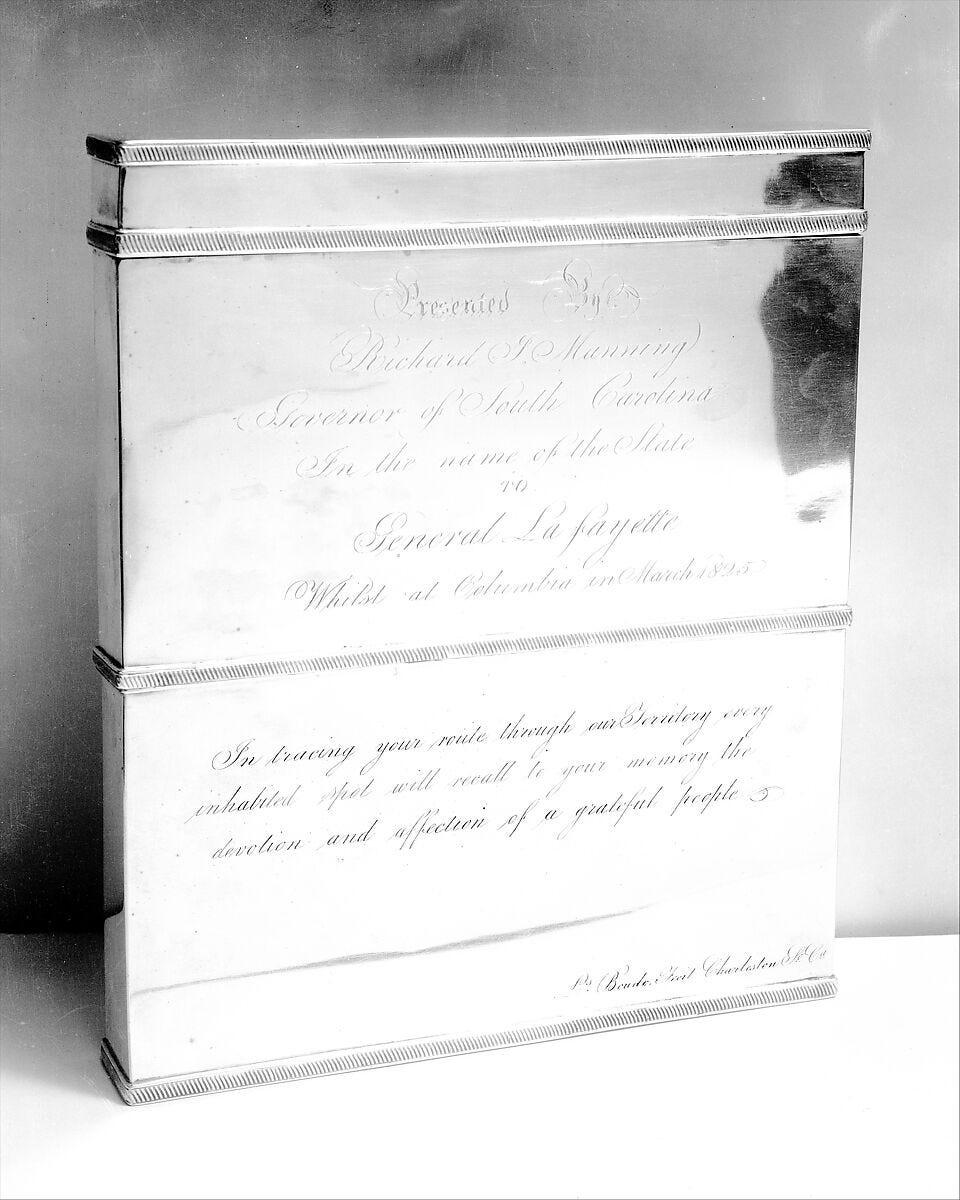

Boudo’s best-known piece is a silver map case made on behalf of the state of South Carolina for General Lafayette during his farewell tour of America in 1825; this case is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The inscription on the map case says:

Presented by Richard I. Manning, Governor of South Carolina, in the name of the State, to General Lafayette whilst at Columbia in March 1825

In tracing your route through our Territory every inhabited spot will recall to your memory the devotion and affection of a grateful people

Other famous silver objects made by Boudo and marked “ls. boudo” or “boudo” in Roman capitals in a scroll or shaped rectangle, include: a decanter label held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art; a pap boat (for feeding infants and “invalids”) owned by the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem, North Carolina; and other pieces in the Charleston Museum and private collections. Boudo died in Charleston on January 11, 1827.

Following Louis’s death, his wife Heloise Boudo administered his estate and continued in the “manufactory of gold and silver work” at various addresses on King Street, paying cash for gold and silver and carrying on the jewelry business “in all its branches.” While Heloise Boudo was not known to have been personally trained in the bench-trade of silversmithing like her late husband, she nevertheless “managed a staff of craftsmen and sold large quantities of silver bearing her mark,” both locally manufactured and imported from the northeast for the Lowcountry market.

Heloise Boudo’s silver work was typically marked with “h. boudo” in a rectangle accompanied by three pseudo hallmarks. She was one of few female silversmiths in nineteenth-century America, and examples of her work are found in the Charleston Museum, Yale University’s Garvan Collection, and private collections.

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

I.

“Summertime,

And the livin' is easy

Fish are jumpin'

And the cotton is high

Your daddy's rich

And your mamma's good lookin'

So hush little baby

Don't you cry

One of these mornings

You're going to rise up singing

Then you'll spread your wings

And you'll take to the sky

But till that morning

There's a'nothing can harm you

With daddy and mamma standing by’”

—Lyrics from the famous aria “Summertime” from the opera Porgy and Bess, written by George Gershwin, Dubose Heyward, and Ira Gershwin

Sources used in today’s newsletter:

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!