#139: SC250: Loyalists in Revolutionary South Carolina, Indigo Workshop, and "This Fierce People"

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, upcoming SC historical events, and other South Carolina recommendations.

Dear readers,

Welcome to SC History Newsletter #139!

Today we continue to dive into Revolutionary War history by learning about South Carolina Loyalists — who were they and what happened to them after the war?

Today’s newsletter is another nod to the SC250 celebration coming up in a little over a year. Be sure to sign up for SC250 updates on their homepage and check out their awesome events page here.

Now let’s learn from SC History!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Support the SC History Newsletter by considering products from our fantastic sponsor Oliver Pluff & Co. — click on their beautiful ad below! :)

➳ Housekeeping for new subscribers!

New friends! There are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and more! See our archive here!

Send me your comments or topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Have additional ideas or feedback? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Keep the conversation going and join over 100 other subscribers by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here!

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

Love the SC History Newsletter? Please click the button below to share with a friend!

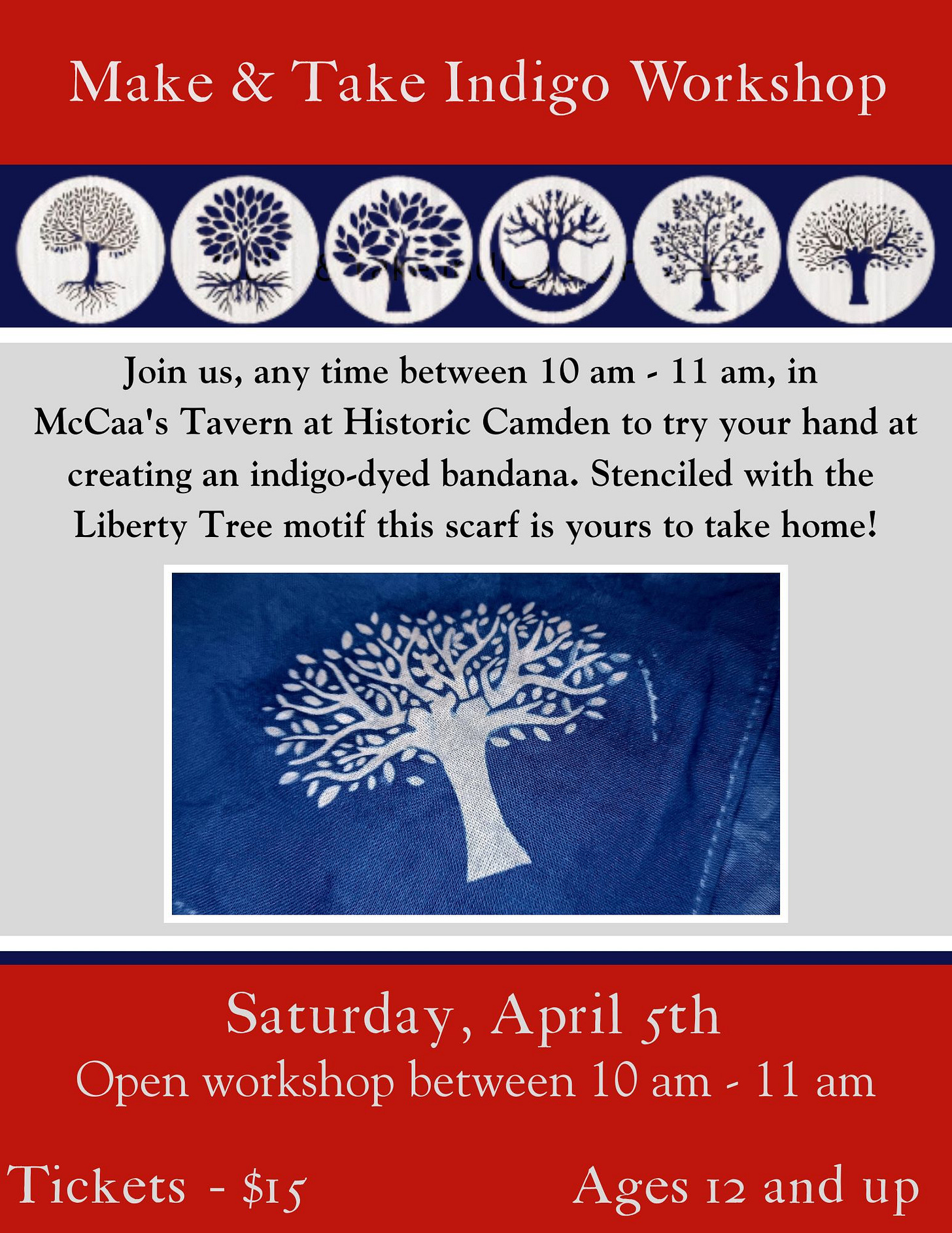

➳ Featured SC History Event of the Week:

Saturday, April 5th at 10:00 am | “Make and Take Workshop: Indigo” | McCaa’s Tavern in Historic Camden | Camden, SC | TICKETS: $15 | Website

As a perk for paid subscribers, click here or the button below to visit my full SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

➳ Other SC History Recommendations

BOOK: This Fierce People by Alan Pell Crawford

From the Publisher:

“A groundbreaking, important recovery of history; the overlooked story—fully explored—of the critical aspect of America’s Revolutionary War that was fought in the South, showing that the British surrender at Yorktown was the direct result of the southern campaign, and that the battles that emerged south of the Mason-Dixon line between loyalists to the Crown and patriots who fought for independence were, in fact, America’s first civil war.

The famous battles that form the backbone of the story put forth of American independence—at Lexington and Concord, Brandywine, Germantown, Saratoga, and Monmouth—while crucial, did not lead to the surrender at Yorktown.

It was in the three-plus years between Monmouth and Yorktown that the war was won.

Alan Pell Crawford’s riveting new book, This Fierce People, tells the story of these missing three years, long ignored by historians, and of the fierce battles fought in the South that made up the central theater of military operations in the latter years of the Revolutionary War, upending the essential American myth that the War of Independence was fought primarily in the North.

Weaving throughout the stories of the heroic men and women, largely unsung patriots— African Americans and whites, militiamen and “irregulars,” patriots and Tories, Americans, Frenchmen, Brits, and Hessians — Crawford reveals the misperceptions and contradictions of our accepted understanding of how our nation came to be, as well as the national narrative that America’s victory over the British lay solely with General George Washington and his troops.”

➳ SC History Topic of the Week:

Loyalists in Revolutionary South Carolina

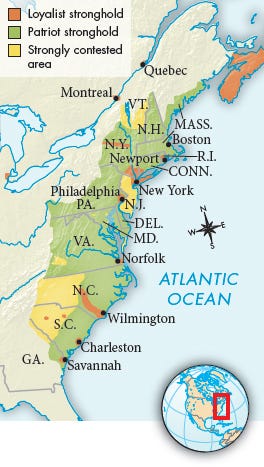

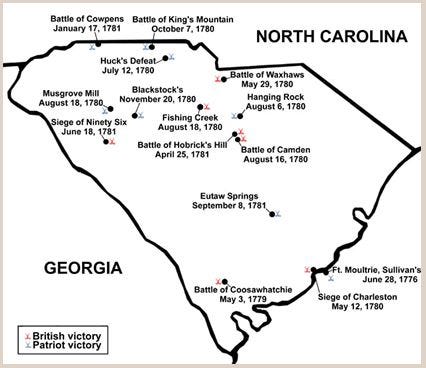

As we have discussed in the newsletter before, South Carolina was the setting for significant Revolutionary War battles and skirmishes that helped deliver victory for the Patriot cause.

It is both fascinating and heartbreaking to understand who exactly was fighting in these battles, as it was often colonists against colonists — Patriots vs. Loyalists — in what would become not only a revolutionary war, but also somewhat of a civil war as well.

Looking back, South Carolina was not a likely place for Revolution to break out.

The colony was one of the richest and most successful in Britain’s empire. The colony’s connections to the England, “the mother country”, were intimately intertwined between the wealthy Lowcountry planters, who worked hand-in-hand with merchants to dispatch their cash crops of rice and indigo from Charleston to England.

The British Royal Navy protected the merchant ships who carried South Carolina crops and products to Great Britain. And Great Britain provided the markets needed to sell South Carolina products.

8 of the 10 wealthiest men in the American colonies resided in South Carolina. The richest was Peter Manigault, who lived in Charleston.

Indeed, those at the top of South Carolina’s political and economic systems “appeared to have almost everything to lose by creating trouble with the mother country."

South Carolinians saw themselves as British citizens, proud of their heritage and connection to Great Britain.

The colonists in South Carolina (like the northern colonies) “had become accustomed to living largely outside the purview of the British Parliament.”

However, the lucrative and symbiotic relationship between Britain and South Carolina began to deteriorate, and quickly — as in other American colonies — due to the commencement of what were considered unfair taxes levied on the colonies.

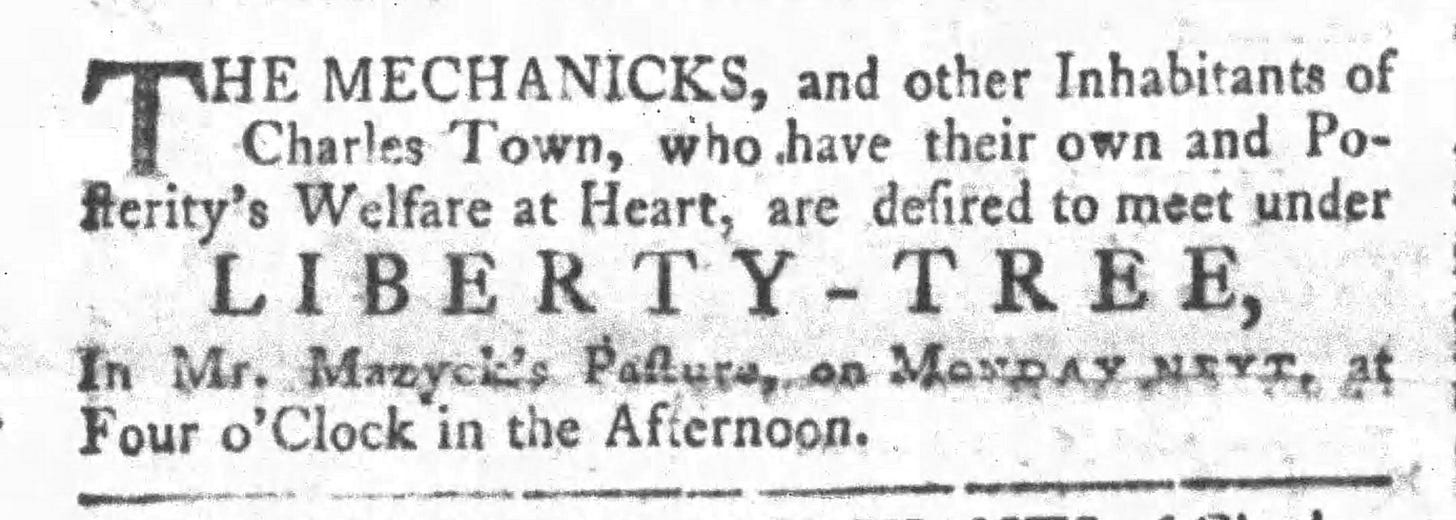

Growing more and more upset about the unfair tax policies, the citizens of Charleston designated a giant oak as their “Liberty Tree” (See SC History Newsletter #131 for more history about the Liberty Tree) and protested the Crown’s unfair taxes. Though at the time, they did not want to separate from the British empire.

When the British Crown cracked down on the colonists in Boston in the aftermath of the Boston Tea Party, the “people of Charleston recoiled in horror.” Seeing a fellow colony have its main port closed by the British showed the enormous power the Crown had to “cripple their way of life.”

Thereafter, “patriotic fervor began to spread” in Charleston.

The citizens of Charleston conducted tea parties of their own where tea delivered from Great Britain to Charleston Harbor was either confiscated or destroyed in protest.

In fact, our amazing newsletter sponsor Oliver Pluff & Co. sells teas that are inspired by these historical events — see their website here! Also see SC History Newsletter #42 to learn about Charleston’s 3 Tea Parties.

As these events unfolded, a provincial government was set up to protect colonists’ interests, and South Carolina sent delegates to the first Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

Tensions in Massachusetts boiled over and the American Revolution began at the Battle of Lexington & Concord in April of 1775.

In South Carolina, “The provincial congress raised regiments of state troops for their defense. The Second Continental Congress established a Continental Army that summer. By September 1775, the Royal Governor of South Carolina was forced to flee from Charleston. Patriot soldiers captured the one main fort in the harbor, Fort Johnson, and raised a new liberty flag over the fort.”

But not every South Carolinian was convinced to join the Patriot war effort.

Those who did not join on the side of the revolutionaries were called Loyalists or Tories, and they allied themselves and/or fought with British forces during the war.

Historians have counted 19 major engagements in South Carolina during the Revolutionary War, and in 16 of those engagements, South Carolina Loyalists made up either 50% or 100% of the British forces!

Carolana.com provides a list of known South Carolina Loyalist Militias and their leaders below.

Many Loyalists were “people who held royal public office…and others were Anglican clergy. Almost a fifth of white South Carolinians stayed loyal to the Crown, but many were African-Americans flocking to the British promise of freedom, or Indians.”

Other Loyalists in South Carolina were people who simply believed in the Rule of Law and saw the British Crown as the legitime source of authority.

Most soldiers in the Upcountry of South Carolina were Loyalists.

Many Upcountry people were not Loyalists in principal but simply wished to “live their lives without interference.” Some Upcountry people were recent immigrants, for example from Germany, who had no allegiance to either the King or to principles of democracy.

So it unfolded that Lowcountry Patriots fought against Upcountry Loyalists during the Revolutionary War.

Here are some stark accounts of the tensions between Loyalists (Tories) and Patriots (Rebels or Whigs) in South Carolina:

“Account of Loyalist plundering: “During this period of several weeks, the Tories [Loyalists] scoured all that region of country daily, plundering the people of their cattle, horses, bed, wearing apparel, bee-gums, and vegetables of all kinds—even wresting the rings from the fingers of the females. Major Dunlap and Lieutenant Taylor, with forty or fifty soldiers, called at a Mrs. Thomson’s, and taking down the family Bible from its shelf, read in it, and expressed great surprise that persons having such a book, teaching them to honor the King and obey magistrates, should rebel against their King and country; but amid these expressions of holy horror, these officers suffered their troops to engage in ransacking and plundering before their very eyes” (found in Lyman C. Draper, Kings Mountain and Its Heroes, 76-77).”

“American General Nathaniel Greene’s account of the situation in the backcountry: “General Greene, a few months later, wrote thus freely of these hand-to-hand strifes: ‘The animosity,’ he said, ‘between the Whigs and Tories, rendered their situation truly deplorable. There is not a day passes but there are more or less who fall a sacrifice to this savage disposition. The Whigs seem determined to extirpate the Tories, and the Tories the Whigs. Some thousands have fallen in this way in this quarter, and the evil rages with more violence than ever. If a stop can not be put to these massacres, the country will be depopulated in a few months more, as neither Whig nor Tory can live’” (quoted in Lyman C. Draper, Kings Mountain and Its Heroes, 139).”

“Account of cycle of vengeance in the backcountry: “Other incidents occurred that fall in the area between Camden and Georgetown. In December, Whigs gained a measure of revenge for the depredations of John Harrison’s provincials by breaking into a house where two of his brothers were recuperating from smallpox and shooting them in their beds. They also engaged in pillaging civilians, one of Rawdon’s patrols finding a house recently visited by a rebel party ‘stripped of everything that could be carried off,’ the woman of the house ‘left standing in her shift,…; her four children stripped stark naked.’ These and similar activities made it difficult for Cornwallis to obtain intelligence because rebel parties ‘have so terrified my people, that I can get nobody to venture far enough out to ascertain anything’” (found in Robert Stansbury Lambert, South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution, 200).”

“Port Royal minister’s description of conditions in the backcountry in 1781: “‘All was desolation…Every field, every plantation, showed marks of ruin and devastation. Not a person was to be met with in the roads. All was Gloomy.’ All society, he continued ‘seems to be at an end. Every person keeps close on his own plantation. Robberies and murders are often committed on the public roads. The people that remain have been peeled, pillaged, and plundered. Poverty, want, and hardship appear in almost every countenance. A dark melancholy gloom appears everywhere, and the morals of the people are almost entirely extirpated’” (quoted in Robert M. Weir, Colonial South Carolina: A History, 336).”

In 1775, a large effort was organized by the Patriots to identify and silence Loyalists in South Carolina.

In July of 1775, the Patriot’s “Council of Safety” sent out Chief Justice William Henry Drayton and Rev. William Tennant to the South Carolina backcountry to persuade those citizens to sign the “Continental Association.” Many refused to sign it.

Drayton and Tennant were escorted through the dangerous backcountry by Col. William Thomson, commander of the SC 3rd Regiment of Rangers. This trip lasted until October of 1775, and it was “instrumental in the Patriots determining who the most vocal Loyalists were in all areas of the province.”

Later that year, many of the high-profile Loyalists identified by this initiative were “rounded up and taken to Charlestown, where they were imprisoned, tried, and mostly found innocent of any real charges. Some escaped this and went directly to the new Royal Governor, who was himself exiled to the man-o-war Tamar in the Charletown Harbor.”

An infamous Loyalist was Richard Pearis, who was a Loyalist Officer and first European settler of Greenville, SC.

Pearis was a frontiersman and trader, who was licensed by the British government and developed deep ties with the Cherokee Nation. He would eventually serve as an interpreter to the Cherokee and would purchase land that would become the heart of Greenville.

Pearis became an instrumental figure in the Upcountry Loyalist forces. He was involved in the first siege of Ninety-Six and arrested during the 1775 Snow Campaign. He was jailed in Charleston for 9 months.

While Pearis was in prison, Cherokee warriors and Loyalists used his property in the upcountry as a meeting place — which further cemented Pearis as an enemy in the eyes of the Patriots. This was enough cause for the Patriots to “burn his home, store and mill and force his family to flee.” By the time he agreed to swear allegiance to the Patriots, Pearis was under so much suspicion that Colonel Andrew Williamson rejected his pledge outright.”

From SC250.org, here is the rest of Pearis’ fascinating story:

“After his imprisonment, Pearis walked from Charleston into the Cherokee Nation and eventually to Pensacola, Florida behind British lines where he joined the South Carolina Royalists, a unit of Loyalists being formed there. He assisted with British-Indian diplomacy in Pensacola and St. Augustine, using his connections from decades working in the Indian trade with the Cherokee and Muskogee Creek. In 1780, Pearis returned to South Carolina with the British army and began rallying support for the Loyalist cause. He reunited with his family in Augusta, GA, where his son was serving in the King’s Carolina Rangers under Thomas Brown. Father and son fought together for the British until the Patriots captured Augusta in June 1781. Fleeing Augusta, Pearis and his family temporarily resettled in St. Augustine until, upon news that Florida would return to the Spanish, they evacuated to the Bahamas. There, Pearis lived out the rest of his life as a planter. The newly formed state of South Carolina confiscated his land in the upcountry — now part of Falls Park on the Reedy — but Pearis is remembered as the namesake of Paris Mountain and Paris Mountain State Park.”

The Patriots had the upper hand throughout the province and state until Charlestown fell to the British army in May of 1780. At that point in time, Loyalist fever surfaced and “many companies and regiments were established, with the assistance of the British army, who wanted more and more to join their ranks.”

At the end of the Revolutionary War in September 1783, the vast majority of Loyalists throughout the United States stayed on to become citizens of the new country. Though many decided to leave to settle in New Brunswick or Nova Scotia. Some would eventually return to the U.S. from Canada where life was “too difficult.”

In South Carolina, many Loyalists voluntarily left South Carolina for the Caribbean or Canada. Others were “fined or run out of town.”

Though South Carolina had seen a “bitter bloody internal civil war in 1780-1782”, the colony adopted a policy of reconciliation that “proved more moderate than any other state.” About 4,500 white Loyalists left when the war ended, but the majority remained.

During the war, pardons were offered to South Carolina Loyalists who switched sides and joined the Patriot forces. Others were required to pay a 10% fine of the value of the property. The legislature named 232 Loyalists liable for the confiscation of their property, but most appealed and were forgiven.

If you voted just “OK” on the newsletter today, I want to hear from you! Reply to this email and send me your feedback. :)

➳ Sources — Loyalists in Revolutionary South Carolina

Brannon, Rebecca. From Revolution to Reunion: The Reintegration of the South Carolina Loyalists. University of South Carolina Press, 2016.

"Charleston in the Revolutionary War." American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/charleston-revolutionary-war. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

"Learn About Loyalists During the Revolution in South Carolina." SC in Vietnam, https://scinvietnam.com/learn-about-loyalists-during-the-revolution-in-south-carolina/. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

"Materials for American Revolution Soldier Trunk." National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/common/uploads/teachers/lessonplans/Materials%20for%20American%20Revolution%20Soldier%20Trunk.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

"Rebellion in the Backcountry: William Henry Drayton and William Tennent Debate Loyalty and Rebellion." America in Class, https://americainclass.org/sources/makingrevolution/rebellion/text4/backcountrydraytontennent.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

"Revolutionary War in South Carolina – Loyalists." Carolana, https://www.carolana.com/SC/Revolution/revolution_sc_loyalists.html. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

"South Carolinians in the Revolution." University of South Carolina Digital Collections, https://digital.library.sc.edu/blogs/academy/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2011/08/South-Carolinians-in-the-Revolution-8-2.22.pdf. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

"The Reintegration of South Carolina Loyalists after the Revolutionary War." The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History, 7 July 2017, https://earlyamericanists.com/2017/07/07/the-reintegration-of-south-carolina-loyalists-after-the-revolutionary-war/. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.

"Upstate Loyalists." South Carolina American Revolution Sestercentennial Commission (SC250), https://southcarolina250.com/story/upstate-loyalists/. Accessed 30 Mar. 2025.