#83: The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon, the burning of Middleton Place, and Mapping Charleston's Black Burial Grounds

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #83 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

Snesbitt1977

rockcarson

boydfua

emeryclark

emoore55OLMC

nathanheyde1

tannerjadon99

jslovensky7

dakotalw726

jwrdr1

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Tuesday, June 11th from 5:30-7:30 pm | “Mapping Charleston’s Black Burial Grounds” | Ila Hall | Charleston, SC | FREE event

“The Preservation Society of Charleston and Anson Street African Burial Ground Project invite you to join us on Tuesday, June 11, 5:30 – 7:30 PM at ILA Hall (1142 Morrison Dr.) for a Mapping Charleston’s Black Burial Grounds Project Preview.

Following a year-long engagement period, this will be the community’s first look at the draft map created in response to resident input that will be used to better protect burial grounds citywide. We are seeking resident input to make this resource the best it can be and hope you can join us.

All are welcome! Please share the invitation with family, friends, and neighbors and let us know if you plan to join us by registering online.

Through 2024, the project team will work with the community to identify, research, and define the locations and boundaries of burial sites to inform a data layer, which will be integrated into the City’s databases as a planning and preservation tool.

Black history has been severely under-collected and underrepresented and often exists more so in personal memories, oral tradition, photographs, and family papers than in formal archives. With this in mind, outreach efforts are underway to provide a platform for community members to shape this project by sharing their knowledge of Black burial sites significant to their neighborhood and family histories. The PSC is honored to be partnering with members of the Anson Street African Burial Ground Project (ASABG) research team, La’Sheia Oubre and Joanna Gilmore, to facilitate this dialogue.

In summer 2023, the PSC and ASABG hosted a series of listening sessions throughout the City of Charleston to provide community members the opportunity to learn more about the project and share information about burial grounds important to them. If you were not able to attend in person, you can tune into a virtual listening session on YouTube.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Did you know that on August 5, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was read to South Carolinians for the first time from the steps of The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon in Charleston?

Finished in 1771, The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon is one of the oldest buildings in Charleston and has played an important role throughout Charleston’s history — in particular, during the Revolutionary War.

The Old Exchange was built to serve as the customs house for Charleston and was at the center of much of the city’s business dealings.

Inside the building was a basement, a main floor where business occurred, and a Great Hall on the second floor for special events.

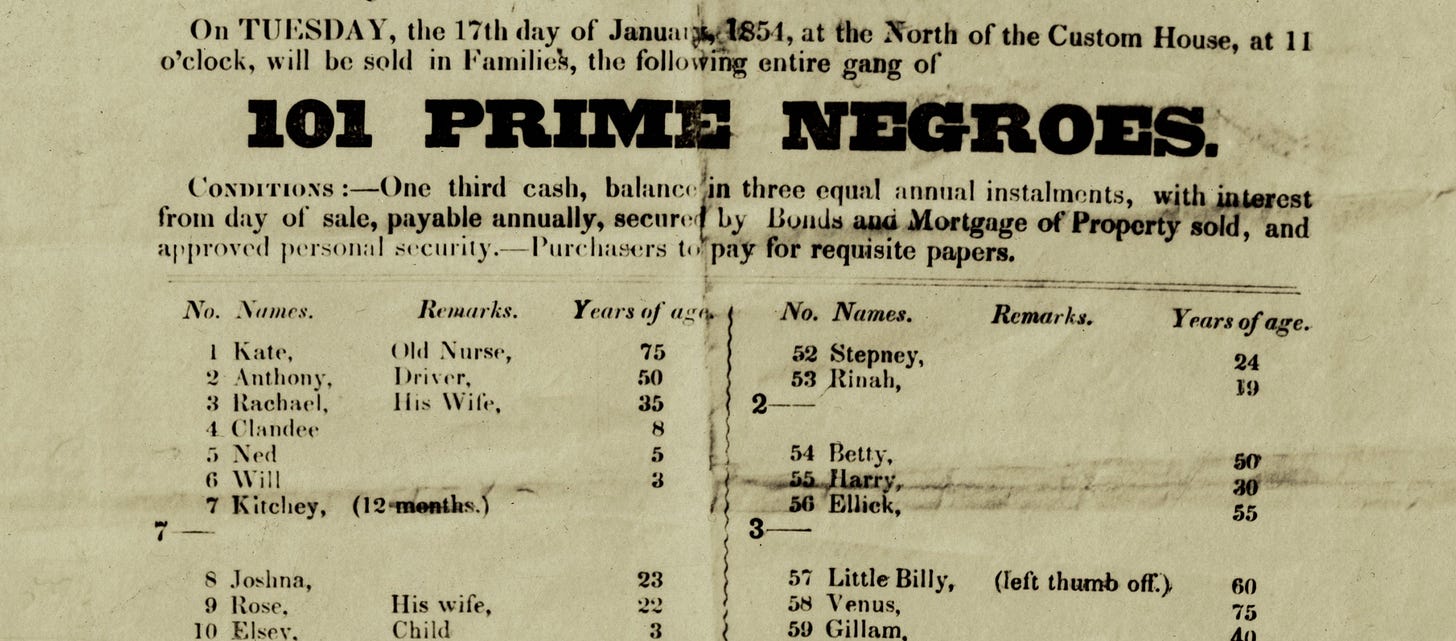

Charleston was a major port city in the slave trade, and auctions of slaves “frequently occurred in the Exchange and just outside on the north side of the building.”

In 1773, the Old Exchange was the scene of protests against British taxation on tea (one of Charleston’s own “tea parties”) and hundreds of chests of contraband tea were stored in the basement and later sold to “help fund the Patriot cause.”

In 1774, South Carolina representatives elected delegates to attend the First Continental Congress in the Exchange Building.

The Old Exchange was also a location for reading important proclamations, such as on August 5, 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was read to a crowd from the steps of the Old Exchange Building.

There is an annual reading of the Declaration of Independence at the front of the Old Exchange Building each July 4th in Charleston.

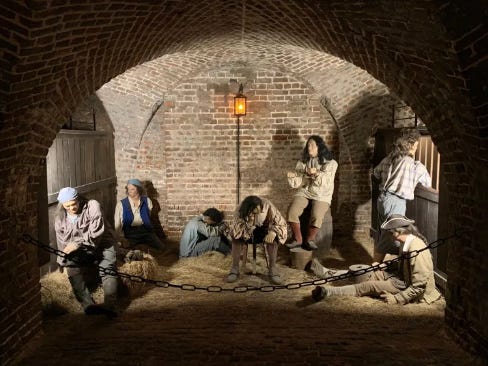

During the siege of Charleston in 1780, General William Moultrie moved thousands of pounds of gunpowder stored in the city’s Powder Magazine (a building where gunpowder is stored) to the basement of the Old Exchange and “bricked it up to keep it safe.” Following Moultrie’s death, the British army occupied the building. The basement was turned into a prison (or Provost Dungeon) for American Patriots, criminals, and British soldiers.

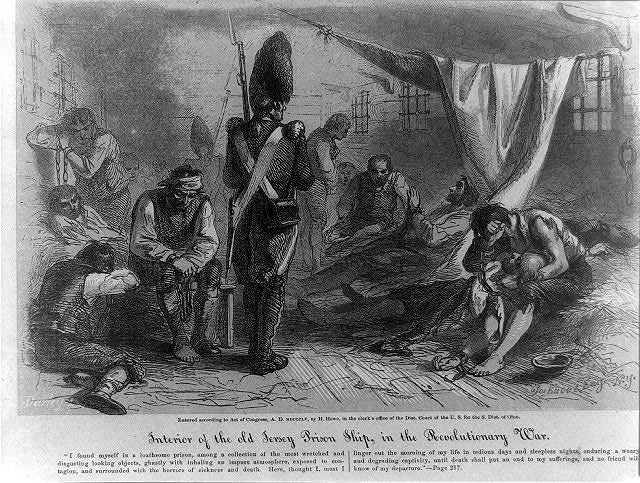

While some American Patriots were held as prisoners in the Old Exchange Building, the vast majority ended up on British prison ships in Charleston harbor. Approximately 800 Continental prisoners of war died of disease on the prison ships during the war.

After the Americans liberated Charleston in 1782, General William Moultrie’s gunpowder was found behind the brick wall — the British never realized that the supplies were hidden beneath their feet throughout the occupation.

After the Revolutionary War, the Old Exchange was the site of South Carolina’s ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788.

In 1791 President George Washington made his first and only visit to Charleston. He was welcomed into the city at the Old Exchange and was lavishly entertained on multiple occasions at the Great Hall.

In SC History Newsletter #22 we explored Washington’s trip to Charleston, and here were some descriptions of the festivities at the Old Exchange:

On May 3rd, 1791 a gathering was held at the Old Exchange Building where many toasts were raised and “an artillery piece would be fired for every toast to General Washington” to signal to those not personally at the event to toast the General from their homes.

On May 4th, once again at the Old Exchange building, Washington attended a ball in his honor, where he noted in his diary, “There were 256 elegantly dressed & handsome ladies.” Many women wore ribbons and sashes that read “Long Live the President” or “GW.”

On May 5th, Washington attended a concert (also at the Old Exchange Building) where he noted in his diary, “…at least 400 ladies—the Number & appearances of which. Exceeded any thing of the kind I had ever seen.”

Throughout most of the 19th century, the Old Exchange served as a United States Post Office “after a new Customs House was built further up on East Bay Street.” It was in this capacity when it was taken over by South Carolina authorities during the American Civil War.

The Old Exchange was damaged by Union cannon fire during the Civil War but survived.

In 1913 the Old Exchange was transferred to the South Carolina Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). The Daughters of the American Revolution continue to own the building and lease the museum's operation to the city of Charleston. Today, the museum highlights the city’s rich Revolutionary War history — check out its website here!

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Have you to the Old Exchange & Provost Dungeon? Please tell us about your visit in the comments below!

II.

Let’s discuss the burning of Middleton Place in 1965 and the chaotic aftermath for the newly emancipated workers on the property

Middleton Place is a historic plantation located on the Ashley River just outside Charleston.

It was established on land originally granted in 1675 but probably not settled until it passed to John Williams in the early eighteenth century. Henry Middleton (1717–1784) acquired the property through his marriage to Williams’s daughter Mary in 1741.

Middleton added to the original acreage and built the elegant gardens that have made Middleton Place internationally famous. As the birthplace of Henry Middleton’s son Arthur (1742–1787), a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Middleton Place was listed in the National Register of Historic Places and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1971.

The gardens, thought to be “the oldest surviving formal landscaped gardens in the United States,” are renowned for their collection of Camellia japonicas, introduced about 1786 by the French Royal botanist André Michaux.

In 1990 the United Nations International Committee on Monuments and Sites named Middleton Place one of six United States gardens having international importance.

The Middleton Place Foundation has identified 2,800 enslaved individuals owned by the Middleton family from 1738 to 1865.

During the Civil War, on February 23, 1865, the original Middleton Place plantation house — described as “three stories tall, built of brick in Jacobean-style — was burned to the ground by the Union Army.

Middleton Place has been the home of Williams Middleton. Middleton had long since evacuated the plantation with his family.

As the crumbling ruins of Middleton Place burned, a “whole community of people was thrust into chaos, uncertainty, and maybe even hope for the future.”

The 56th New York Regiment of Volunteers “had come through and presented the Union’s message in no uncertain terms, and in the following days they moved on, leaving the formerly enslaved community at Middleton Place with the experience of a sudden and violent emancipation.”

A Union Army surgeon from Massachusetts named Dr. Dr. Henry Orlando Marcy witnessed the range of emotions that accompanied the emancipation of previously enslaved people. Marcy was in attendance both before and after the destruction. He first describes the tumultuous scene of emancipation:

“Continued on to [Middleton Place] which I found splendidly located in the midst of extensive pleasure grounds on a slight eminence. All here was confusion. [The slaves] had heard the news from their friends and they were making ready to leave. [Williams Middleton] had left about a week previous . . . [His] overseer had soon followed and for some days the Col[ored] people had been alone. Everything was in confusion. The house was strewed with articles and all about the grounds things were scattered…Met the driver and learned much of interest. The Colored people flocked around me and gave numerous demonstrations of joy. All wanted to ‘shake hands.’ Guess this is a custom of theirs. The Driver a very intelligent man, said he was placed in charge of a [party and teams] to go up country but he had contrived to get away with the whole party and return.”

Upon his return the following day, Dr. Marcy expressed sorrow for the destruction of the built environment — especially the library — of Middleton Place, but he was also concerned about the enslaved workers and what was next for them. According to Dr. Marcy:

“…the col.[ored] people were robbed indiscriminately. My first object was to get the col[ored] people together and advise them what to do — find there is a schooner and several flats here and as they are all determined to leave I advise them to load the boats and proceed to the city. . . Accompanied by the driver I rode down to the [Horse Savannah / Jerry Hill] five miles away. Here found about 150 slaves. Called them together and made them a little talk…The col[ored] people seem happy and are making ready to leave for town.”

Dr Marcy, a likely abolitionist, he was able to offer a life-changing opportunity to one particular formerly enslaved woman from Middleton Place. Priscilla Johnson (or Johnston), was born enslaved to the Middletons in 1846, and had been assigned to work in the gardens at Middleton Place before the Union troops arrived. Dr. Marcy offered her the job as a nurse-companion for his mother back in Cambridge, MA. Priscilla, newly free and able “for perhaps the first time in her life to make a decision about her future,” agreed to go with Dr. Marcy.

After Marcy’s mother passed away, Priscilla chose to remain in the North, marrying a freedman, Madison Robinson of Virginia, in 1872. The couple had 3 daughters of their own, and Priscilla would go on to nursemaid for at least two more families.

While Priscilla did not ever return to Middleton Place, her living descendants have. Priscilla’s family has been in contact with Middleton Place Foundation, visited the National Historic Landmark, and attended the 2011 Reunion of Descendants of Middleton Place.

Middleton Place continued in the Middleton family until 1984, when ownership was vested in the nonprofit Middleton Place Foundation.

Middleton Place includes:

A museum housed in what was originally the south flank of the former three-building main residence

A plantation chapel built in 1850 above the eighteenth-century springhouse

A rice mill built in 1851

An 1870s African American freedman’s house in the reconstructed stable-yards complex

Middleton Place is open to the public every day of the year except Christmas. Please visit the Middleton Place website to learn more!

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Have you visited Middleton Place? Tell us about your experience in the comments below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“In our society, it is accepted that we set aside homes where great men are born, but in this house, South Carolina was born.”

—Hobart G. Cawood, speaking at the Old Exchange rededication (1981)

The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon article sources:

“History – Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon.” Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon, https://www.oldexchange.org/highlights. Accessed 3 May 2024.

“The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon.” American Battlefield Trust, 20 Sept. 2023, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/old-exchange-and-provost-dungeon. Accessed 3 May 2024.

“The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon.” Daughters of the American Revolution, https://www.dar.org/national-society/historic-sites-and-properties/old-exchange-and-provost-dungeon. Accessed 3 May 2024.

The Burning of Middleton Place article source:

“Beyond the Fields, Slavery at Middleton Place.” Middleton Place, https://shop.middletonplace.org/products/beyond-the-fields-slavery-at-middleton-place. Accessed 3 May 2024.

“Middleton Place Beyond The Fields Tour, Guided African American Slave History, Eliza House.” Middleton Place Historic Landmark, Charleston Tour, Plantation, & Gardens, https://www.middletonplace.org/explore/elizas-house/. Accessed 3 May 2024.

“Upheaval and Freedom come to Middleton Place.” Middleton Place, 2 Feb. 2021, https://www.middletonplace.org/news-and-events/february-23-1865-upheaval-and-freedom-come-to-middleton-place/. Accessed 3 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!