#86: Strom Thurmond, the Willie Earle Lynching Case, and a new book on Confederate General James Longstreet

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #86 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

toddgantt100

brookscpb

williamrivers42866

Simmonpd

leslie.weirmeir

thecapps03

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Tuesday, August 20th from 6:00 - 7:00 pm | “Speaker Series: Elizabeth Varon's Latest Biography “Longstreet” | Charleston Library Society | Charleston, SC | $10 members, $15 non-members

“Elizabeth Varon’s LONGSTREET is a bold new biography of the Confederate general whose support of constitutional rights for Black Americans after the Civil War enraged Southern critics and ignited a campaign to destroy his reputation. General James Longstreet fought tenaciously for the Confederacy. He was alongside Lee at Gettysburg (and counseled him not to order the ill-fated attacks on entrenched Union forces there). He won a major Confederate victory at Chickamauga and was seriously wounded during a later battle.

After the war Longstreet dramatically changed course. He supported Black voting and joined the newly elected, integrated postwar government in Louisiana. When white supremacists took up arms to oust that government, Longstreet, leading the interracial state militia, did battle against former Confederates. His defiance ignited a firestorm of controversy, as white Southerners branded him a race traitor and blamed him retroactively for the South’s defeat in the Civil War.

Although he was one of the highest-ranking Confederate generals, Longstreet has never been commemorated with statues or other memorials in the South because of his postwar actions in rejecting the Lost Cause mythology and urging racial reconciliation.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

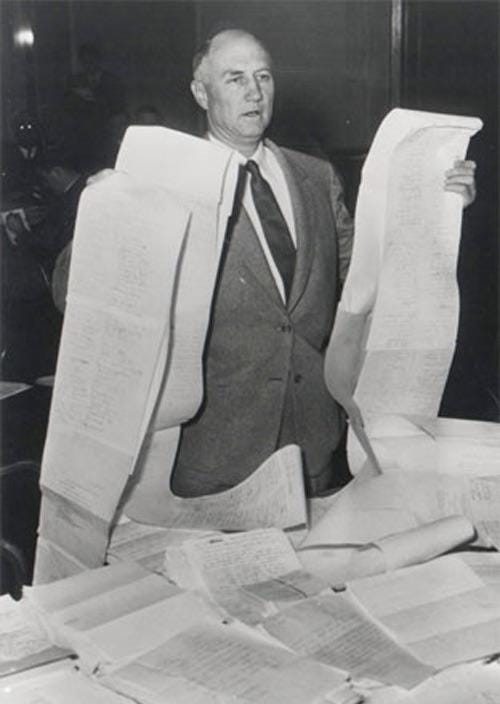

Did you know that SC Senator Strom Thurmond holds the record for the longest ever filibuster at 24 hours and 18 minutes?

Strom Thurmond was born in Edgefield, SC on December 5, 1902, to John William Thurmond and Eleanor Gertrude Strom.

His father was a community leader of some repute and notoriety — in fact, Thurmond’s father “killed a man in a fight in 1897, claiming self-defense.”

James Strom was the second of 6 children. His parents immediately dropped “James,” and thereafter, he was known as “Strom.”

Thurmond got an early taste for politics, as his family home was a gathering place for the political elite. Thurmond listened attentively to the lively discussions over Sunday dinner.

When he was 9 years old, he watched a gubernatorial debate. Entranced “with the energy of the moment, he resolved that one day he would be governor.”

Thurmond earned a bachelor of science degree from Clemson College in 1923. He was a part of the school’s championship cross county and track teams.

Here are a few excerpts about Thurmond from his 1923 TAPS Clemson yearbook:

“There have been few boys at Clemson who have succeeded in making everything a success to the extent that Strom has… Strom’s athletic ability found expression on the cinder path. Although having to work hard, he proved to be a good point winner and a fair representative of the purple and gold.” (Note: Purple and gold were the colors of Clemson at the time).

“Nor did anyone think this handsome young man was to become a ladies’ man of the ‘first water’, and was to create so many extra heart beats among the fairer sex.”

From an obituary for Thurmond published by Clemson in 2003:

“Thurmond’s athletic prowess at Clemson laid the foundation for a long and healthy life. Thurmond was well-known for his fitness and did not smoke or drink alcohol while serving as senator at the nation’s capital. He did pushups daily well into his 90s and for his 65th birthday party he entertained media and assembled guests by performing 100 pushups. He also fathered four children after age 66, and his social reputation was documented by TAPS in 1923”

His first job was teaching at the white school in McCormick.

In 1928 he won his first political office as superintendent of the Edgefield County schools. Shortly after he started his work, he began studying law with his father. He passed the state bar in December 1930.

Early the next year, he was appointed Edgefield’s town attorney and combined those duties with private law practice.

Thurmond won a seat in the state Senate in 1932, where he served until 1938. In his first term, he “championed legislation to improve the public schools, which earned him a commendation from state teachers. His continuing efforts on behalf of education won him a seat on the Winthrop College Board of Trustees. Years later the college named a building after him.”

From the SC Encyclopedia:

“In 1937 Thurmond ran for an open judicial seat against the better-known George B. Timmerman. The state legislature elected judges, and Thurmond brazenly asked House speaker Sol Blatt and Senator Edgar Brown, both pledged to Timmerman, to stay neutral. When the lawmakers met on January 13, 1938, Thurmond had corralled so many votes that Timmerman withdrew his name.”

The Anderson Independent called Thurmond’s victory “a political upset of major proportions, which stunned even those who usually feel that they know what is going to happen.”

Thurmond was reelected to a full judicial term in 1940 without challenge. He volunteered for the army in World War II, although he was old enough to avoid service.

As a member of the 82d Airborne Division, he was wounded during the D-day landing in France when his glider crashed behind German lines.

In the meantime at home, Thurmond had been reelected without opposition, and after he left the army he resumed his judicial duties.

Seven months after returning, on May 15, 1946, Thurmond resigned from the bench to run for governor.

Thurmond campaigned unapologetically against the “Barnwell Ring,” the powerful group of legislators headed by state Representative Solomon Blatt and state Senator Edgar A. Brown, and promised “to bring a new spirit to South Carolina governance.”

Thurmond ran first in the August primary and easily defeated James McLeod in the September runoff.

Inaugurated on January 21, 1947, Thurmond introduced a “progressive agenda championing more money for education, including the impoverished black schools, and encouraging women to serve in government.”

He garnered positive national attention for dispatching a government prosecutor to Greenville, SC to try the brutal Willie Earle lynching case. (Note from Kate: we will explore this case in the next essay below)

On November 7, 1947, Thurmond married Jean Crouch, one of his secretaries and 23 years his junior. He infamously posed for Life magazine standing on his head in front of Jean with the caption “VIRILE GOVERNOR.”

Jean Thurmond died in 1960 of a brain tumor. They had no children.

From the SC Encyclopedia:

“The most significant moment of Thurmond’s governorship occurred outside of South Carolina and was directly related to the growing national ferment over race. Up to this moment Thurmond had stayed clear of any direct racial disputes, but now he was drawn into the debate between southern Democrats and the national party over civil rights. Though relatively inexperienced and less well known than long-serving southern senators, Thurmond emerged as a leader in the states’ rights movement. A central tenet was the belief that the states had complete freedom to regulate social affairs within their borders — “custom and tradition” in Thurmond’s benign euphemism for segregation.”

While delegates from Mississippi and Alabama bolted the July 1948 Democratic convention in Philadelphia, Thurmond held the South Carolina delegates in check. A few days later he went to the states’ rights gathering in Birmingham. Responding to urgent entreaties, he agreed to carry the group’s banner in the presidential election.

In a racially charged speech accepting the nomination as the States’ Rights Democratic Party candidate, Thurmond said, “I want to tell you that there’s not enough troops in the army to force the southern people to break down segregation and admit the Negro race into our theaters, into our swimming pools, into our homes, and into our churches.”

Thurmond and his Presidential running mate, Mississippi governor Fielding Wright (dubbed the “Dixiecrats”), carried only Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina.

In 1950 Thurmond challenged incumbent U.S. senator Olin D. Johnson but was defeated in the Democratic primary. It was the only election Thurmond ever lost.

He returned to his law practice after his gubernatorial term, but “politics beckoned again in 1954.”

After the unexpected death of U.S. Senator Burnet Maybank barely two months before the next election, Democratic Party leaders selected Edgar Brown to be his replacement over objections from those who favored a more open process.

Thurmond was cajoled into running as a write-in candidate and prevailed over Brown in the November election with a stunning 63.1 percent of the votes.

Despite the events of 1948, Thurmond promised that he would participate in the Senate’s Democratic caucus. He had also promised to resign and run for a full term in 1956.

Though friends urged Thurmond to ignore his resignation promise, he refused. He came back to South Carolina and “coasted to reelection in 1956 when no one filed to run against him.”

In the meantime Thurmond “burnished his segregationist credentials.” He was the major force behind the “Southern Manifesto” in 1956, a broadside that counseled resistance to the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision that mandated the desegregation of public schools.

The next year Thurmond set the record for a filibuster (24 hours, 18 minutes) when he spoke against a civil rights bill that eventually passed.

The election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 and Kennedy’s subsequent moves on civil rights created renewed disaffection.

When Lyndon Johnson assumed the White House after Kennedy’s assassination and pressed civil rights legislation with even more vigor, Thurmond, “though not the architect of the southern resistance, was a vocal and consistent opponent of every new bill.”

Unhappy with the Democrats’ political drift and acting against the advice of friends and associates, Thurmond switched parties when Arizona Republican Barry Goldwater secured the 1964 GOP nomination for president. Thurmond claimed, “The Democratic Party has abandoned the people.”

Though he would not be the most important southern Republican in the decades to come, he was at the forefront of the region’s political realignment, and in 1968 he was an important part of Richard Nixon’s vaunted “southern strategy.”

The emerging political realignment in the South was “fueled in large part by the transformation of the electorate from all-white to white and black.” The critical element was the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which Thurmond, like every other Deep South senator, opposed.

But time would demonstrate Thurmond’s ability to adjust to new realities. He hired a black man, Thomas Moss, to his Senate staff. Thurmond also began “to court the growing number of black politicians in the state and paid more attention to black communities seeking federal help.”

In a changed electorate, “he should have been a prime target for defeat, but even as a Republican he won easy reelection in 1966, 1972, and 1978.”

On December 22, 1968, Thurmond married Nancy Moore, a former Miss South Carolina forty-four years his junior. They had 4 children by 1977, and the family proved to be an asset in his successful race in 1978 against an accomplished and much younger opponent, Charles “Pug” Ravenel.

The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 and the return of the Senate to Republican control gave Thurmond his first committee chairmanship, of the Judiciary Committee, and at a dramatic moment. The man with a reputation as the “standard-bearer for segregation” now headed the committee that handled the renewal of the all-important Voting Rights Act. Thurmond “chose not to play obstructionist politics and ended up supporting the renewal bill. The next year he backed a federal holiday honoring Martin Luther King, Jr.”

Democrats regained control of the Senate from 1987 to 1994. When Republicans took over again after the 1994 election, Thurmond became chairman of the Armed Services Committee and president pro tempore of the Senate. But at age ninety-two, he was a figurehead; the day-to-day work was done by others.

Reelected to a seventh term in 1996, he relinquished the chairmanship at the end of 1998, a concession to his advancing age and infirmities. Thurmond focused on his ceremonial role as Senate president, but his frail condition required him to give up those duties early in 2001.

Thurmond became the oldest senator ever. He completed his final Senate term and then retired to a special suite in the Edgefield County Hospital. He died in Edgefield on June 26, 2003, and was buried in Willowbrook Cemetery.

Six months after Thurmond died, Essie Mae Washington-Williams, a 78-year-old woman who lived in Los Angeles, came forward to say that she was the child of Thurmond and Carrie Butler, who in 1925 had been a sixteen-year-old black maid working for the Thurmonds in Edgefield.

Thurmond had long been rumored to have fathered a black child, but he always denied it, as did Williams, saying for years that “she was simply a family friend.”

When she came forward in December 2003, Williams said that Thurmond had maintained a private relationship with her, “helping financially over the years.” Thurmond’s son, J. Strom Jr., said that the family would not contest Williams’s claim.

2005, Williams released a book called Dear Senator that recounted her life story and relationship with her father Strom Thurmond. Here is an excerpt from Williams’ book:

“For all his bluster, for all his racist campaign posturing, I somehow couldn't dislike him the way I wanted to...Even though on the surface he had it all, high office, a perfect wife, health and wealth and power, I--and only I--new how deeply conflicted he had to be. I knew he loved my mother. I believed he loved me, after his fashion. It was an unspeakable love, forbidden by the 'culture and custom' of the South, as he called it. The money was speaking it for him. It wasn't hush money; it wasn't a bribe. It was the governor's own outpouring of love and shame and frustration. He had no other way to demonstrate his affection."

Here is a video about Strom Thurmond from the SC Hall of Fame:

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Let’s discuss the Willie Earle Lynching Case in Greenville — 1947

The murder of Willie Earle is believed to be the last racial lynching in South Carolina.

On February 16, 1947, Earle, a 25-year-old Black man from Greenville, was arrested for the robbery and stabbing of a white Greenville taxi driver, Thomas Watson Brown.

The next day, a mob of 35 men abducted Earle from his cell in the Pickens County Jail and drove him to the outskirts of Greenville, where they lynched him.

Earle’s body, “badly mutilated from stab wounds in the chest and shotgun wounds in the head,” was recovered the same day.

Thomas Brown, the original stabbing victim, died hours after Earle. According to some contemporaries — including Earle’s mother, his neighbors, and the executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Walter White — no evidence existed to link Earle to the murder of Brown.

Officials at the state and federal levels were quick to condemn the lynching and to pursue Earle’s murderers.

South Carolina Governor J. Strom Thurmond immediately “denounced mob violence and promised an investigation by state authorities.”

By the end of February, Federal Bureau of Investigation agents, dispatched to Greenville by U.S. Attorney General Tom C. Clark, had obtained signed statements from 26 men who admitted their participation in the lynching.

A Greenville County grand jury subsequently indicted 31 men — most of whom were taxi drivers — for murder, conspiracy to commit murder, and accessory before and accessory after the fact of murder.

Begun on May 12, 1947, the Greenville lynching trial generated interest within South Carolina and throughout the nation.

The New Yorker published an article by Rebecca West about the trial entitled “Opera in Greenville” on June 6, 1947. Here is an excerpt:

“It was impossible to watch this scene of delirium, which had been conjured up by a mixture of clownishness, ambition, and sullen malice, without feeling a desire for action. Supposing that one lived in a town, decent but tragic, which had been trodden into the dust and had risen again, and that there were men in that town who threatened every force in that town which raised it up and encouraged every force which dragged it back into the dust; then lynching would be a joy.”

The simple fact that the trial took place was “evidence of a changing racial order,” as were the efforts of the presiding judge to make the proceedings “as impartial as possible.”

Still, many white South Carolinians sympathized with the defendants, believing that the lynching was regrettable but probably unavoidable in light of the crime for which Earle was accused.

After a trial of 10 days, in which the defense declined to present any witnesses or evidence, the jury found the defendants not guilty on all counts.

Appalled, the judge “refused to thank the jury for their service.”

The most significant legacy of the Earle case “was to stimulate efforts on behalf of civil rights.” According to leaders in the Progressive Democratic Party of South Carolina, the lynching “strengthened the resolve of Black Carolinians, a development that helped accelerate political activism throughout the state.”

The Earle case also influenced officials at the federal level, including President Harry S. Truman and members of his President’s Committee on Civil Rights.

Exposing the limitations of state efforts to prevent mob violence and to promote racial equality, the Earle lynching and the acquittal of the lynch mob played a key role in convincing the Truman administration to take a stronger stand for federal action to defend civil rights.

Here is a video remembering Willie Earle from the City of Greenville, SC:

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“His [Strom Thurmond’s] favorite question, which he asked whenever he saw me, was "How does it feel to be the daughter of the governor?" My answer was always the same: "It doesn't bother me at all." I was trying to joke with him, but he took it with a stone face. To him, I suppose our deep secret wasn't a joking matter. Still, this was the first time he himself had verbally acknowledged that I was his child. He used the D-word, which he had not done in our previous meetings."

— Excerpt from Essie Mae Williams’ book Dear Senator

Strom Thurmond article sources:

Coleman, Korva. “Essie Mae Washington-Williams Dies, Mixed Race Child Of Strom Thurmond : The Two-Way : NPR.” NPR, 6 Feb. 2013, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2013/02/06/171273089/essie-mae-washington-williams-dies-mixed-race-child-of-strom-thurmond. Accessed 6 May 2024.

Cohodas, Nadine. “Thurmond, James Strom.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/thurmond-james-strom/. Accessed 6 May 2024.

“Dear Senator- Part IV.” Carol Baldwin’s Blog, https://carolbaldwinblog.blogspot.com/2013/06/multi-racial-read-13-dear-senator-part.html. Accessed 6 May 2024.

“Thurmond Left Mark On Clemson Athletics.” Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site, 27 June 2003, https://clemsontigers.com/thurmond-left-mark-on-clemson-athletics/. Accessed 6 May 2024.

Willie Earle Lynch Trial article sources:

Mack, Adam. “Earle, Willie, Lynching of.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, 17 May 2016, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/earle-willie-lynching-of/#:~:text=(February%2017%2C%201947).,taxi%20driver%

2C%20Thomas%20Watson%20Brown. Accessed 6 May 2024.LaFleur, Elizabeth. “Ask LaFleur: Who Was Willie Earle and Who Is behind His Historical Markers?” The Greenville News, 18 Oct. 2018, https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news/local/asklafleur/2018/10/18/ask-lafleur-who-willie-earle-and-who-behind-his-historical-markers/1656659002/. Accessed 6 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!