#116: SC's role at the Constitutional Convention, Greer Graveyard tours, and Civil Rights

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, interviews w/ experts, book recommendations, and upcoming SC historical events.

Dear reader,

Welcome to SC History Newsletter #116!

I hope everyone has continued to stay safe in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene.

Many here in Greenville are still without power, but we hope it will be restored soon. And we keep our neighbors in Western North Carolina in our thoughts every day.

While it is hard to talk about anything other than Hurrican Helene, I did want to share some other personal news that I recently joined the Nathanael Greene chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) here in Greenville, SC. My great grandmother was a DAR life member, and with my love of American History and my desire to be of service, I decided to follow in her footsteps. Turns out I am related to a handful of Revolutionary War Patriots, but the easiest one for them to trace to me was a Virginian soldier named: Sackfield McLynn Bracy. What a name!

Every year, DAR celebrates “Constitution Week” from September 17 - September 23, to honor when the final draft of the Constitution was signed by 39 delegates in Philadelphia on September 17th, 1787. I was inspired to learn more about how our South Carolina Founding Fathers contributed to our U.S. Constitution and that is the subject of our main history article today.

As always, I’d like to welcome the following new subscribers to our community. Thank you for your interest in South Carolina history!

oakwoodnc

cosminonlinecanspam

marsha01

billray01

wtkbakj

theusc

armproductionfr

f2gorman

New friends! If you are new to the newsletter, please note that there are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and so much more! I encourage you to take a look at our archive here.

Send me your topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you. :)

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Events

Please note our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered.

Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

Event Recommendation of the Week:

Dates throughout October | “Greer Ghost Tours: Graveyard Tour” | Greer City Cemetery | Greer, SC | Tickets & information

“The Graveyard Tour, Murder & Mayhem, includes “new” stories that haven’t been told in a hundred years. Learn something new about Greer’s history! These are fun, family-friendly walking tours which begin on Jason Street beside the Greer City Cemetery and end at the Greer Heritage Museum. Each tour will take about an hour. Note that this walking tour does go on unfinished surfaces (grass, gravel) and have curbs and steps. In case of rain, meet at the Greer Heritage Museum. We recommend parking at the Jason Street Garage.”

➳ SC History Book, Article, & Movie Recommendations

“In Darkest South Carolina” by Brian Hicks

(Note from Kate: This book is written by our former guest on the podcast, Brian Hicks!)

Publisher’s description:

"Four years before the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, a federal judge in Charleston hatched his secret plan to end segregation in America. Julius Waties Waring was perhaps the most unlikely civil rights hero in history. An eighth-generation Charlestonian, the son of a Confederate veteran and scion of a family of slave owners, Waring was appointed to the federal bench in the early days of World War II. Faced with a growing demand for equal rights from black South Carolinians, and a determined and savvy NAACP attorney named Thurgood Marshall, Waring did what he thought was He followed the law, and the United States Constitution. This is the story of Judge J. Waties Waring, his incredible life and the country he changed"

Have you read “In Darkest South Carolina”? Tell us your review! Leave a comment below!

➳ SC History Topic of the Week:

South Carolina’s role in the creation of the U.S. Constitution

The United States Constitution was drafted during the long, hot summer of 1787 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Before the Constitution, the colonies were governed by The Articles of Confederation, which were ratified in 1781, during the Revolutionary War (1775-1783). During this time, “the nation was a loose confederation of states, each operating like independent countries. The national government was comprised of a single legislature, the Congress of the Confederation; there was no president or judicial branch.”

After America won the Revolutionary War in 1783, it became clear to our Founding Fathers that the Articles of Confederation and the colonies’ early system of government were no longer meeting the needs of the new nation.

In 1786, Alexander Hamilton, a lawyer and politician from New York (whose life has been immortalized in the Broadway show Hamilton), called for a Constitutional Convention to discuss, debate, and hopefully improve our fledgling nation’s system of government.

In May of 1787, 55 delegates arrived at the Constitutional Convention at Independence Hall in Philadelpha — the very same place where the Declaration of Independence had been adopted 11 years prior in 1776.

These delegates came from 12 of the 13 states. Rhode Island did not send any delegates to the convention because the state feared that a more powerful central government “would interfere in its economic business.”

A chief aim of the Constitution as drafted by the Convention was to “create a government with enough power to act on a national level, but without so much power that fundamental rights would be at risk.”

The number of delegates sent to the Constitutional Convention was determined by the population of the state and the state's political significance.

Here is the breakdown of the number of delegates from each state:

Pennsylvania: 8 delegates

Virginia: 7 delegates

Delaware: 5 delegates

Maryland: 5 delegates

Massachusetts: 4 delegates

New Jersey: 5 delegates

North Carolina: 5 delegates

South Carolina: 4 delegates

Georgia: 4 delegates

Connecticut: 3 delegates

New Hampshire: 2 delegates

New York: 3 delegates

Rhode Island: 0 delegates (Did not attend)

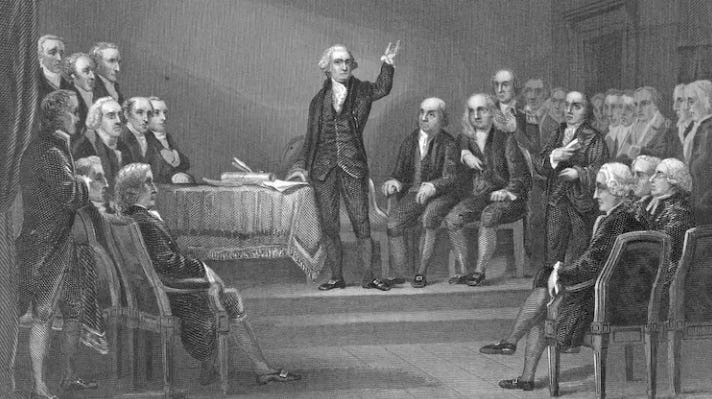

The Constitution was drafted in Independence Hall from May 25th to September 17, 1787. George Washington was “unanimously elected” as the president of the convention, though he had originally been reluctant to attend.

After the Revolutionary War, George Washington retired to Mount Vernon with a goal to live out his days as a “country squire.” His retirement wouldn’t last long. He couldn’t escape politics, as he received many political visitors at Mount Vernon who kept him abreast of the latest news. Washington also had many worries during this time: worries about affairs on the American frontier, worries about a “quasi-royal central government” that seemed to be forming, and worries that if he should involve himself in the Constitutional Convention, he would look power-hungry — and he did not want that perception to besmirch his military accomplishments. Eventually, James Madison and General Henry Knox convinced George Washington to attend. Everyone believed Washington would play a central role in their new government.

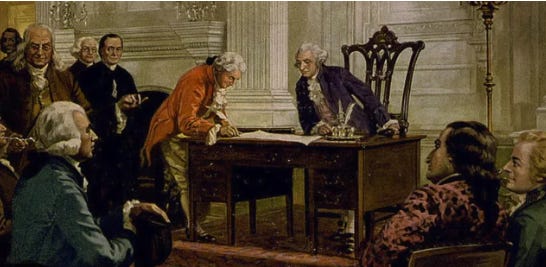

As the discussions began, all the delegates — who would also be called the “framers” of the Constitution — were sworn to secrecy. Even in the midst of a brutally hot summer, the windows of Independence Hall were closed to keep any and all discussions private. Without modern air conditioning, one can clearly imagine our Founding Fathers sweaty and irritable as they debated and argued over what would become the bedrock of our American Democracy.

Here is the scene described by William P. Kladky from the Mount Vernon website:

“The Convention met in Independence Hall through a typically hot and steamy Philadelphia summer. The delegates' sweltering was heightened by their decision to meet in secret and to seal the windows shut. As the delegates argued Washington observed, while sitting on a tall wooden chair on an elevated platform in front. Wearing his old military uniform, Washington participated little in the debates, seeing his function as nonpartisan, to maintain or restore order when debate became too boisterous. The role perfectly fit Washington's dignified, discreet nature. Washington intervened infrequently, and mostly to vote for or against the various proposed articles. When not in session, Washington toured the city accompanied by his enslaved workers. To avoid the crowds' emotions and staring, he often ventured out early in the morning.”

Here are some other interesting writings and excerpts about the process of writing the Constitution from various Founding Fathers:

James Madison writing on the challenges of consensus:

“The real wonder is that so many difficulties should have been surmounted, and surmounted with a unanimity almost as unprecedented as it must have been unexpected. It is impossible for any man of candor to reflect on this circumstance without partaking of the astonishment.” — James Madison, Federalist No. 37

Benjamin Franklin writing on compromise:

“I confess that I do not entirely approve of this Constitution at present; but, Sir, I am not sure I shall never approve it: For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. [...] Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best.” — Benjamin Franklin, September 17, 1787

Note that Benjamin Franklin was the oldest delegate and was known to add humor and levity to the room if/when discussions became too heated.

Elbridge Gerry, delegate from Massachusetts, reflecting on the urgency of compromise during the Convention:

“If we do not come to some agreement among ourselves, some foreign sword will probably do the work for us.” — Elbridge Gerry

Alexander Hamilton remarked on what might happen if the Constitution failed:

“A torrent of angry and malignant passions will be let loose. To judge from the history of mankind, we shall be driven into anarchy.” — Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 1

As we “zoom out” on the Constitutional Convention, it is also important to note that about 30% of the delegates were slaveowners.

According to Brittanica.com:

“The Constitutional Rights Foundation asserts that 17 of the 55 delegates were enslavers and together held about 1,400 enslaved people. In addition to identifying James Madison as an enslaver, Signers of the Constitution, published in 1976 by the National Park Service, notes that 11 other signers “owned or managed slave-operated plantations or large farms,” and then it names them: Richard Bassett, John Blair, William Blount, Pierce Butler, Daniel Carroll, Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer, Charles Pinckney, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, John Rutledge, Richard Dobbs Spaight, and George Washington. It is also known that Benjamin Franklin enslaved people.”

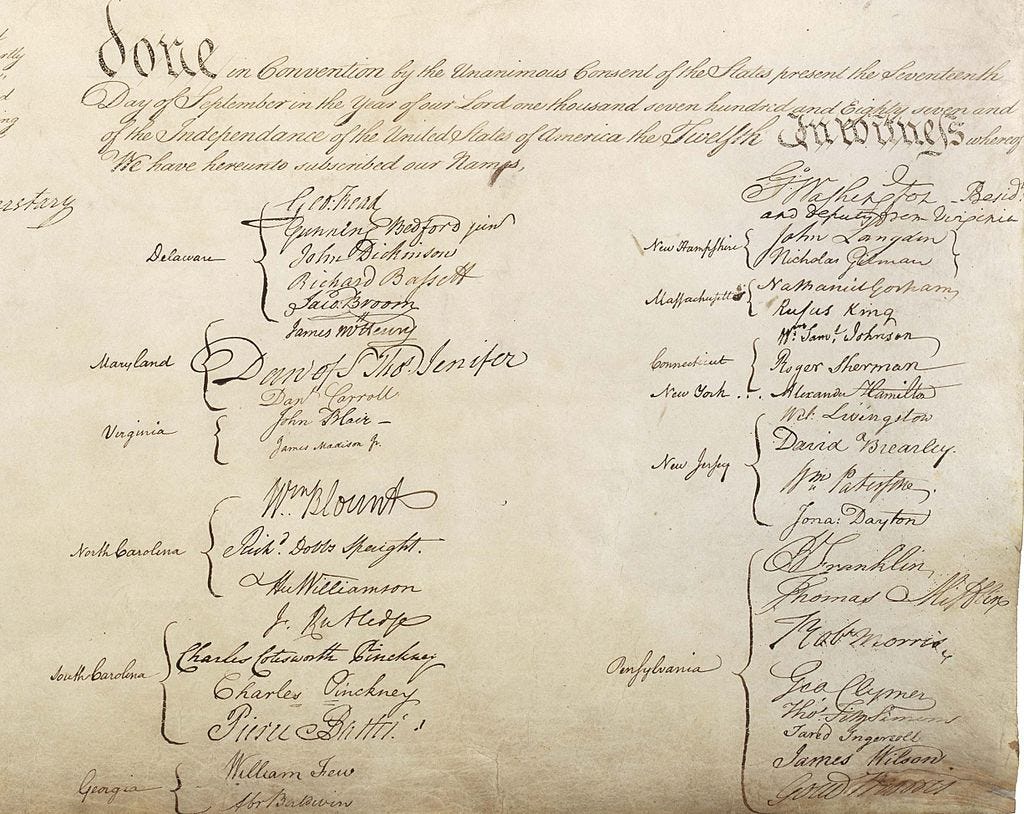

South Carolina sent 4 delegates to the Constitutional Convention: John Rutledge, Charles Pinckney, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, and Pierce Butler. As you may recognize from the bullet above, all of South Carolina’s delegates were slaveowners, and this fact would greatly influence many of their contributions to the Constitutional Convention.

Let’s learn more about each of South Carolina’s delegates at the Constitutional Convention:

John Rutledge: Born in Charleston, John Rutledge was a lawyer and a politician who has served as a delegate for South Carolina at First and Second Continental Congresses, served as the first governor of South Carolina, and later on would serve as one of the original associate justices of the Supreme Court, and would become the 2nd Chief Justice of the United States.

John Rutledge (Image Source: Supreme Court History) Charles Cotesworth Pinckney: An influential statesman and Revolutionary War hero and diplomat, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney was a strong advocate for a robust federal government and later ran for president in 1804 and 1808, representing the Federalist Party.

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (Image Source: Wikipedia Images) Charles Pinckney: A cousin of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Charles Pinckney was a prominent political figure, planter, and would later serve as a governor of South Carolina, as well as a senator and a member of the House of Representatives.

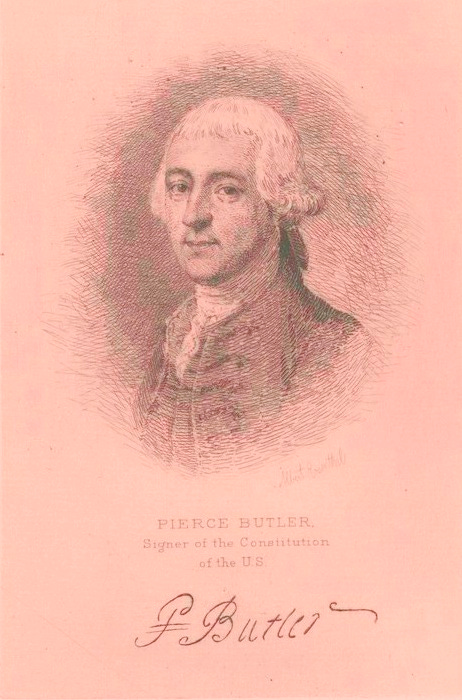

Charles Pinckney (Image Source: Wikipedia) Pierce Butler: Born in Ireland in 1744, Pierce Butler originally served in the British Army before he resigned and immigrated to South Carolina in 1773. Due to Butler’s experience as a British soldier, he was recruited by fellow Founding Father Governor John Rutledge to lead the American opposition to Britain’s Southern Campaign in the Revolutionary War. After the war, Butler served as a state legislator and would later serve on the US Senate. He was also one of the largest slave holders in the United States.

Let’s learn about how each South Carolina delegate contributed to the Constitutional Convention:

John Rutledge: A deeply respected lawyer, Rutledge played a key role at the convention as the Chairman of the Committee of Detail, which helped put the discussions of the delegates into words and draft the Constitution itself. Rutledge also had “a major role in the enumeration of congressional powers, the provision forbidding taxation of exports, and the ban on national prohibition of slave imports until 1808.”

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney: Pinckney staunchly defended the rights of Southern slaveholding planters and argued for the continuation of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Pinckney argued that "while there remained one acre of swampland uncleared of South Carolina, I would raise my voice against restricting the importation of negroes....the nature of our climate and the flat, swampy situation of our country, obliges us to cultivate our lands with negroes, and that without them South Carolina would soon be a desert waste...” Pinckney also commented on the irony and duality of American freedom and American slavery when he said, "Bills of Rights generally begin with declaring that all men are by nature born free. Now, we should make that declaration with a very bad grace, when a large part of our property consists in men who are actually born slaves."

Charles Pinckney: Cousin of fellow delegate Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Charles Pinckney came the Constitutional Convention with his own draft of a constitution, which he called the “Pinckney Plan.” Scholars today “attribute 28 clauses of the Constitution to Pinckney.” He was such a strong voice at the convention, he was even given the nickname “Constitution Charlie.” His major contributions included:

The elimination of religious testing as a qualification to office.

The division of the Legislature into House and Senate.

The power of impeachment being granted only to the House.

The establishment of a single chief executive, who will be called President.

He suggested the idea of presidential term limits, originally proposed to be seven years.

The power of raising an army and navy being granted to Congress.

The prohibition of states to enter into a treaty or to establish interfering duties.

The regulation of interstate and foreign commerce being controlled by the national government.

Pinckney also vehemently defended the institution of slavery. He stated South Carolina would reject the Constitution if the document prohibited the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Pierce Butler: As one of the largest slaveholders in the United States, Butler frequently defended American slavery for both political and personal motives, even though he had “private misgivings about the institution and particularly about the Atlantic slave trade.” He introduced the Fugitive Slave Clause into a draft of the Constitution, which “gave a federal guarantee to the property rights of slaveholders.” Butler also supported counting the entire slave population in state totals for Congressional apportionment. The Constitution's “Three-fifths Compromise” counted only three-fifths of the enslaved population in state totals but still led to white voters in Southern United States having disproportionate power in the United States Congress.

To go a bit deeper into the “Three-fifths Compromise”: this was a compromise agreement between Northern and Southern delegates on how the states would determine their population size, and thus their taxation and representation in the House of Representatives, as well as in the Electoral College.

The issue of population centered around the issue of slavery. There were many heated discussions about slavery at the Constitutional Convention, and our South Carolina delegates were strong voices in these debates.

From the African American Intellectual History Society:

“Each section’s interest demanded that it argue against its own principles. Northern delegates were loath to inflate southern power, and so argued that the Constitution should not count slaves at all, since they were property and no other forms of property were to be considered. Asked Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, why should “blacks, who were property in the South,” he declared, count toward representation “any more than the Cattle & horses of the North”? Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania wondered “upon what principle is it that the slaves shall be computed in the representation? Are they men? Then make them Citizens and let them vote. Are they property? Why then is no other property included?” William Patterson of New Jersey “could regard negro slaves in no light but as property. They are no free agents, have no personal liberty, no faculty of acquiring property, but on the contrary are themselves property, & like other property entirely at the will of the Master.”

Southern delegates, fearful of a free North overwhelming them in the future, argued that since representation was to be based on population, the slaves should be thought of as people; each should thus be considered as a full person, despite being denied basic rights. Pierce Butler of South Carolina responded that the matter at issue was the relative wealth of the states. Because “the labour of a slave in S. Carola. was as productive & valuable as that of a freeman in Massts.,” he believed that “an equal representation ought to be allowed for them in a Government which was instituted principally for the protection of property.”

The issue of determining population was a crucial issue. Many Founding Fathers were against slavery, believing that it violated the ideals of liberty so central to the American Revolution, but in the end, the framers of the Constitution “continued to privilege the maintenance of unity of the new United States over the eradication of slavery.” The institution of slavery was too entrenched in the economies and way of life of the Southern States — it could not be eradicated (yet).

Ultimately, the framers reached a compromise, deciding that representation in the House of Representatives would be based on a state's free population plus three-fifths of its enslaved population. This agreement became known as the Three-Fifths Compromise. Excerpt from the Constitution:

“Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three-fifths of all other Persons.”

The discussions and debates continued at the Constitutional Convention for 116 days from May 25th to September 17th, 1787 — when 39 of the 55 delegates actually signed the drafted Constitution. Certain delegates could not attend or chose not to attend that day (out of protest) to sign their names.

Jonathan Dayton of New Jersey, aged 26, was the youngest to sign the Constitution, while Benjamin Franklin, aged 81, was the oldest.

The Constitution was written in 1781, ratified in 1788, and in operation in 1789.

Let us end this section of the newsletter today with the beautiful Preamble of the Constitution:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

➳ Sources — SC’s Role in the US Constitution

"10 Facts about Charles Cotesworth Pinckney." Friends of Charles Pinckney National Historic Site, https://friendscnp.org/10-facts-charles-cotesworth-pinckney/. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Avalon Project: Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787." Yale Law School, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/debates_705.asp. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Charles Pinckney." National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/chpi/learn/historyculture/charles-pinckney.htm. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Charles Cotesworth Pinckney." National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/charles-cotesworth-pinckney.htm. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Constitutional Convention." Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/constitutional-convention/#:~:text=With%20Madison's%20skillful%20personal%20courting,to%20seal%20the%20windows%20shut. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Constitution of the United States." National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/founding-fathers. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Constitutional Convention." The White House, https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/our-government/the-constitution/#:~:text=the%20United%20States.-,The%20Constitutional%20Convention. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History." Library of Congress, https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/text-1-10. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Guest Editorial - On Constitution Day, Madison's Greatest Triumph." The Daily Progress, 15 Sept. 2017, https://dailyprogress.com/news/community/greenenews/opinion/guest-editorial----on-constitution-day-madisons-greatest-triumph/article_3628a9aa-9899-11e7-ae5b-4b0e4140675e.html. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"How Many of the Signers of the US Constitution Were Enslavers?" Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/story/how-many-of-the-signers-of-the-us-constitution-were-enslavers. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"John Rutledge." National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/john-rutledge.htm. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

Painter, Nell Irvin. “A Compact for the Good of America: Slavery and the Three-Fifths Compromise.” African American Intellectual History Society (AAIHS), 1 Aug. 2017, https://www.aaihs.org/a-compact-for-the-good-of-america-slavery-and-the-three-fifths-compromise/. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Records of the Federal Convention of 1787." University of Chicago Press, https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/a7s3.html. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"The Constitution of the United States." History, https://www.history.com/topics/united-states-constitution/constitution. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"The Senate and the United States Constitution." United States Senate, https://www.senate.gov/about/origins-foundations/senate-and-constitution/constitution.htm. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"The Senate and the United States Constitution." United States Senate, https://www.senate.gov/about/origins-foundations/senate-and-constitution.htm#:~:text=On%20August%206%2C%201787%2C%20the,did%20not%20elicit%20any%20debate. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Signers of the Constitution." USConstitution.net, https://www.usconstitution.net/constnotes-html/#Sigs. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

"Signers of the Constitution." National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/founding-fathers#:~:text=In%20all%2C%2055%20delegates%20attended,39%20actually%20signed%20the%20Constitution. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!