#57: The first Memorial Day, Beaufort National Cemetary, and a Park Day volunteer event at Battle of Rivers Bridge State Historic Site

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #57 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

Here’s a little welcome/update audio message:

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new free subscribers — woohoo!

sailer3636

nancydavidson08

tinasroyster

dnv0125

julie.moser

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, April 13th at 11:30 am | “Park Day volunteer event at Battle of Rivers Bridge State Historic Site” | SC State Parks & American Battlefield Trust | Ehrhardt, SC | Info here

“Calling all history buffs, community leaders, and preservationists! On Saturday, April 13th, 2024, mark your calendars for a day of meaningful impact as we participate in Park Day, an annual event by the American Battlefield Trust. Now in its 28th year, Park Day unites thousands of volunteers nationwide to help maintain and restore historic sites.

Schedule of events:

9:30am – 10:30am FREE Battlefield Tour

11:30am – 1:00pm Volunteer event- Stain Battlefield Fence

1:00pm - 1:30pm FREE Lunch

2:00pm - 3:30pm Civil War Camping Program, free to Park Day volunteers.

Volunteers can come to the Park Office early for a free ranger-led tour of the battlefield at 9:30am! We’ll be staining the fence and gate at the battlefield, followed by a free lunch of hotdogs, chips, and water. All volunteers will receive a free Park Day 2024 bag and have the option to participate in our Civil War Camping program from 2:00pm to 3:00pm, regularly $5, FREE of charge. For more information about Park Day at Rivers Bridge State Historic Site, please contact Russell Stock by phone at 803-683-0239 or by e-mail at rstock@scprt.com.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Did you know that the earliest recorded Memorial Day celebration happened in Charleston and was a parade organized by freed slaves who walked along the (formerly beautiful) Washington Race Course, while commemorating those who had died in the war?

Listen to this section in the mini audio voiceover below!

Today I am inspired by an article by Dave Roos that I read on History.com, which discusses the amazing circumstances of how Yale University professor David Blight discovered America’s first Memorial Day — a discovery that gives even more poignant meaning to the holiday. I summarize the article below:

The Civil War produced unimaginable tragedy. 600,000 to 800,000 Union and Confederate soldiers died in the “single bloodiest military conflict in American history.”

The United States had to find a way to honor those who had died in the war. The first national commemoration of Memorial Day was held in “Arlington National Cemetery on May 30, 1868, where both Union and Confederate soldiers are buried.”

One of the first iterations of Memorial Day was called “Decoration Day” because it was a time when family members would decorate the graves of their relatives who died in the war. Several towns and cities across the US claim to have started the tradition.

But then 1996, a remarkable discovery occurred in a dusty Harvard University archive.

David Blight, a professor of American History at Yale University, was researching a book on the Civil War when “he had one of those once-in-a-career eureka moments.” A curator at Harvard’s Houghton Library asked if he wanted to look through two boxes of unsorted material from Union veterans. “There was a file labeled ‘First Decoration Day,’” remembers Blight, still amazed at his good fortune. “And inside on a piece of cardboard was a narrative handwritten by an old veteran, plus a date referencing an article in The New York Tribune. That narrative told the essence of the story that I ended up telling in my book.”

Professor Blight had discovered the earliest recorded Memorial Day commemoration “organized by a group of Black people freed from enslavement less than a month after the Confederacy surrendered in 1865.”

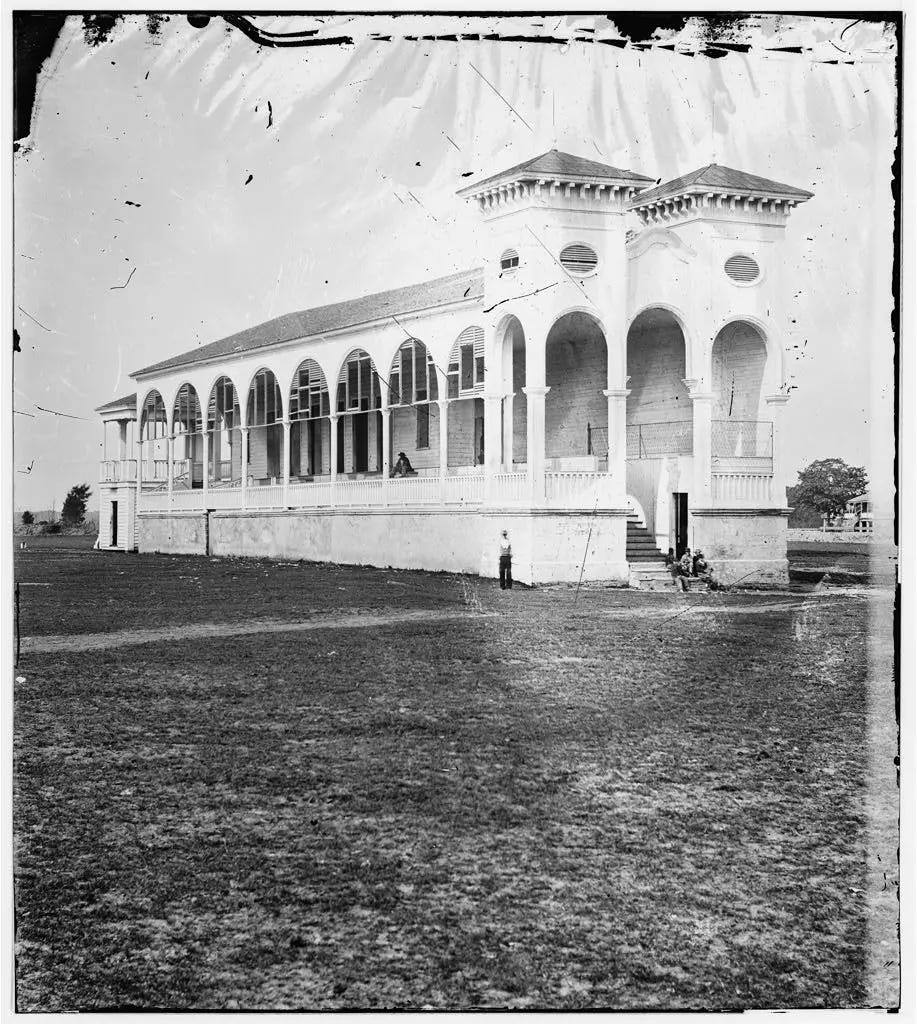

This 1865 commemoration occurred at Charleston’s Washington Race Course and Jockey Club. In the late stages of the Civil War, the Confederate army “transformed the formerly posh country club into a makeshift prison for Union captives.” More than 260 Union soldiers died from disease and exposure while being held in the race track’s open-air infield. Their bodies were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstands.

When Charleston fell to the Union Army and Confederate troops evacuated the badly damaged city, “those freed from enslavement remained.”

The emancipated men and women gave the fallen Union prisoners a proper burial. They “exhumed the mass grave and reinterred the bodies in a new cemetery with a tall whitewashed fence inscribed with the words: ‘Martyrs of the Race Course.’”

Then on May 1, 1865, something even more extraordinary happened. According to two reports that Professor Blight found in The New York Tribune and The Charleston Courier, “a crowd of 10,000 people, mostly freed slaves with some white missionaries, staged a parade around the race track. 3,000 Black schoolchildren carried bouquets of flowers and sang ‘John Brown’s Body.’”

I looked up the “John Brown’s Body” song and immediately recognized it, and I’m sure you will too. To help bring this amazing history alive, here is audio of the song:

Members of the “famed 54th Massachusetts and other Black Union regiments were in attendance and performed double-time marches. Black ministers recited verses from the Bible.”

If the news reports are accurate, the 1865 gathering at the Washington Race Track in Charleston would be the earliest Memorial Day commemoration on record.

After making this discovery, Blight excitedly called the Avery Institute of Afro-American History and Culture at the College of Charleston, looking for more information on the historic event. They were not aware of this historical event and did not have any further information for him.

“This was a story that had really been suppressed both in the local memory and certainly the national memory,” says Blight. “But nobody who had witnessed it could ever have forgotten it.”

Writes Dave Roos: “Once the war was over and Charleston was rebuilt in the 1880s, the city’s white residents likely had little interest in remembering an event held by former enslaved people to celebrate the Union dead. ‘That didn’t fit their version of what the war was all about,’ says Blight.”

Over time, the Washington horse track and country club were torn down, and thanks to a “gift from a wealthy Northern patron,” the Union soldiers' graves were moved from the humble white-fenced graveyard in Charleston to the Beaufort National Cemetery.

The history of this momentous day had been all but forgotten until…

Professor Blight wrote a book Race and Reunion and in 2001, he gave a talk about the history of Memorial Day at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. After the talk was finished, an older Black woman approached him. “You mean that story is true?” the woman asked Blight. “I grew up in Charleston, and my granddaddy used to tell us this story of a parade at the old race track, and we never knew whether to believe him or not. You mean that’s true?”

Writes Roos: “For Blight, it’s less important whether the 1865 commemoration of the ‘Martyrs of the Race Course’ is officially recognized as the first Memorial Day. ‘It’s the fact that this occurred in Charleston at a cemetery site for the Union dead in a city where the Civil war had begun,” says Blight, “and that it was organized and done by African American former slaves is what gives it such poignancy.’”

I’m also adding additional context from an article from the College of Charleston:

Adam Domby, assistant professor of history at the College of Charleston, did additional research in conjunction with Professor Blight’s on the Washington Race Course event. Not surprisingly, “many white southerners who had supported the Confederacy, including a large swath of white Charlestonians, did not feel compelled to spend a day decorating the graves of their former enemies.” Domby is convinced that it was often “African American southerners who perpetuated the holiday in the years immediately following the Civil War.”

Domby writes, “African Americans across the South clearly helped shape the [Memorial Day] ceremony in its early years…Without African Americans the ceremonies would have had far fewer in attendance in many areas, making the holiday less significant.”

How amazing this story is. Have you heard of this early Memorial Day history before? Do you know anyone who has family memories from this event? Leave a comment if so! Or if you just want to further discuss.

II.

After the Civil War, we learned above how Union soldiers’ graves were moved from the “Martyrs of the Race Course” cemetery at the Washington Race Course in Charleston to the Beaufort National Cemetary. Let’s discuss more about the Beaufort National Cemetary below!

Beaufort National Cemetery is a United States National Cemetery located in Beaufort, South Carolina. It is managed by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs and encompasses 44.1 acres, and as of 2024, had over 28,725 interments.

The original interments in the cemetery were men “who died in nearby Union hospitals during the occupation of the area early in the Civil War, mainly in 1861, following the Battle of Port Royal.”

Battlefield casualties from around the area were also reinterred in the cemetery, including over 100 Confederate soldiers.

It became a National Cemetery with the National Cemetery Act by Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

Of the Civil War soldiers buried here, there are: “9,000 Union soldiers (3,607 unknown) 2,800 POWs from the camp at Millen and 1,700 African-American Union soldiers.” There are also 102 confederate soldiers. The remains of 27 Union prisoners of war were reinterred from Blackshear Prison following the war.

Beaufort National Cemetery now has interments from every major American conflict since the Civil War, including the Spanish–American War, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Gulf War.

In 1987, the remains of 19 Union soldiers of the all-black Massachusetts 55th Volunteer Infantry were discovered on Folly Island, South Carolina. The Folly North Archaeological Project (1990) did further excavations in the area after Hurricane Hugo, which revealed artifacts such as “leather shoes, rubberized canvas, wood staves and animal bone.”

The Union Army’s Massachusetts 55th had been stationed on Folly Island from late 1863 to early 1864 and was a sister unit to the better-known Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry, featured in the film Glory (1989), which starred Matthew Broderick, Morgan Freeman, and Denzel Washington.

On May 29, 1989, the 54th soldiers were reinterred in the Beaufort National Cemetery with full military honors. Cast members from the film served as the honor guard at the ceremony. Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis presented the Massachusetts regimental flag to “the color guard as 144 black and white Civil War re-enactors recreated a military burial service in accordance with 1863 Army regulations…The Memorial Day salute for the soldiers was fired by a black Civil War re-enactment group from Boston as a Confederate unit from Georgia stood by.” Governor Dukakis said in his remarks:

Unlike the men and boys who fought and died for a way of life they believed in, and others who did so with equal bravery to establish the sovereignty of the national government, these black soldiers ... fought for their own liberty, to grasp their own freedom and ensure both for others of their own race. Liberty once gained and then neglected is liberty in peril. Oppression once defeated and then forgotten is likely to return. So we do well to gather here today, so close to that place where these brave men, black and white, fought to gain that liberty and suppress that oppression, and died in the effort, as fitting testament to their cherished memory.

Beaufort National Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997.

Here is a trailer for the film Glory, which I have added to my watchlist. I am also inspired to do further research into Black soldiers in the Civil War in South Carolina:

Have you been to the Beaufort National Cemetary? If so, leave a comment below and tell us about your experience!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“Old John Brown’s body lies moldering in the grave,

While weep the sons of bondage whom he ventured all to save;

But tho he lost his life while struggling for the slave,

His soul is marching on.

CHORUS: Glory, glory, hallelujah,

Glory, glory, hallelujah,

Glory, glory, hallelujah,

His soul goes marching on.

— From the song “John Brown’s Body” which was a United States marching song about the abolitionist John Brown. The song was popular in the Union during the American Civil War. The song “arose out of the folk hymn tradition of the American camp meeting movement of the late 18th and early 19th century.” According to an 1889 account, the original John Brown lyrics were a collective effort by a “group of Union soldiers who were referring both to the famous John Brown and also, humorously, to a Sergeant John Brown of their own battalion.”

Sources used in today’s newsletter:

One of the Earliest Memorial Day Ceremonies Was Held by Freed African Americans - History.com

Take an Architectural Tour of SC by Starting with Robert Mills' Designs

Memorial Day Uncovered: Charleston’s ‘Martyrs of the Race Course’

After 126 years, 19 black Union soldiers receive military burial

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!