#87: Charleston Renaissance, Solomon Guggenheim, and Life and Times of Myrtle Beach Air Force Base

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #87 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

martianhunter.20

bookwormbrowning

catccampbell

terrierkelly

aged100

tjacksoncassidy

dgdooley74

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Saturday, May 11th at 1:00 pm | “Life and Times of Myrtle Beach Air Force Base” | Horry County Museum | McCown Auditorium | Conway, SC | FREE

“The Horry County Museum presents a lecture by Col. Thomas ‘Buddy’ Styers on Saturday, May 11, at 1:00 PM. Col. Styers will speak on the life of the Myrtle Beach Air Force Base from 1954-2024.

Colonel Styers serves as the Executive Director of the Myrtle Beach Air Force Base Redevelopment Authority that was established by the South Carolina General Assembly in 1994 to oversee the redevelopment and reuse of the closed Myrtle Beach Air Force Base. He is responsible for the day-to-day management of the Authority and directs the economic development of the former Myrtle Beach Air Force Base. He developed and executed the Authority’s long and short-range goals and objectives to create diversified employment opportunities and to enhance the local tax base. He also represented the Authority with the general public and the media and maintained close liaison with local, state, and federal governmental agencies.”

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

Let’s explore the Charleston Renaissance and how it shaped the city’s cultural revival in the first part of the 20th century

After the very difficult era of Reconstruction, the Charleston Renaissance was a “multifaceted cultural renewal” for the city that took place in the years between World Wars I and II.

Artists, musicians, writers, historians, and preservationists — individually and in groups — fueled a revival that reshaped the city’s destiny.

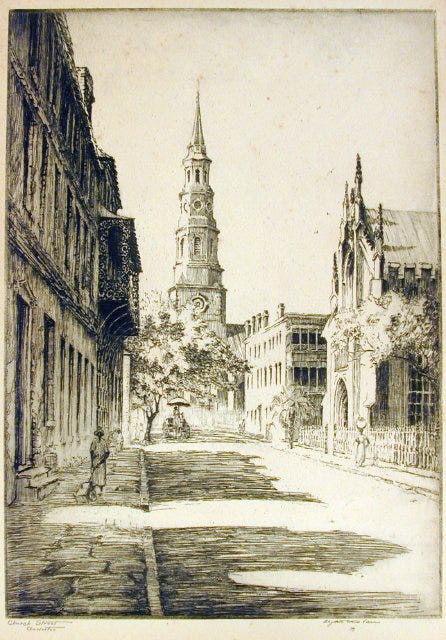

Such organizations as the Charleston Sketch Club and the Charleston Etchers’ Club, the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, the Jenkins Orphanage Band (see SC History Newsletter #78), the Poetry Society of South Carolina, and the Society for the Preservation of Old Dwellings provided opportunities for groups to foster artistic expression deeply rooted in Charleston’s past.

Many individuals, largely natives, were responsible for shepherding these organizations including, “Alice Ravenel Huger Smith and Elizabeth O’Neill Verner; Augustine T. Smythe and Herbert Ravenel Sass; DuBose Heyward, John Bennett, Josephine Pinckney, and Julia Peterkin; Susan Pringle Frost, Alston Deas, and Albert Simons.”

The Charleston Renaissance benefited from a large number of books that were published in this time period that featured entrancing paintings and prints by local artists, as well as documentary photographs, that advertised the beauty of the Lowcountry.

A seminal book was The Dwelling Houses of Charleston, South Carolina, published in 1917 and consisting of house histories by D. E. H. Smith accompanied by picturesque drawings by his daughter, Alice Smith.

Ten years later Albert Simons and his partner Samuel Lapham issued the lavishly illustrated volume The Early Architecture of Charleston.

Both books “instilled a sense of pride in Charleston’s architectural past and stimulated the historic preservation movement.”

Spurred by Susan Pringle Frost (See SC History Newsletter #65), and others active in the preservation society, the municipal government in 1931 passed the nation’s first preservation ordinance and established the Board of Architectural Review to oversee all demolitions and changes to structures in the historic district of Charleston.

That same year in 1931, the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals issued The Carolina Low-Country, a compendium of essays on plantation life, with an emphasis on spirituals. The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals (still in existence) has an amazing website that features recordings of Gullah communities singing heritage spirituals they learned from their enslaved ancestors. I encourage you to visit here.

Here is an excerpt from a Society for the Preservation of Spirituals concert program in 1983:

"The Society evolved in the early 1920's, inspired by the nostalgic sentiments of a group of friends transplanted from their various family plantations to the urban atmosphere of the City of Charleston. Missing acutely the familiar country sights and sounds, they came together informally to sing the haunting songs that were part of their childhood. The Society is proudly amateur in every sense of the word. A book, The Carolina Low Country and recordings over the years — many represented here — are the tangible fruits of their labors. They also provided financial aid each month to several old and indigent country Negroes."

These and the many other books published at this time served to document Charleston’s cultural heritage, and because they were accessible and easily transported, the books served “to disseminate the charms of the Lowcountry to a broad audience.”

The book that probably did the most to turn national attention to Charleston in this time was the novel Porgy, by DuBose Heyward, published in 1925. The story of Porgy began as a novel, then turned into a play on Broadway in 1928, and finally, it was turned into the folk opera Porgy and Bess in 1935. Here is the famous aria “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess, which you may likely recognize:

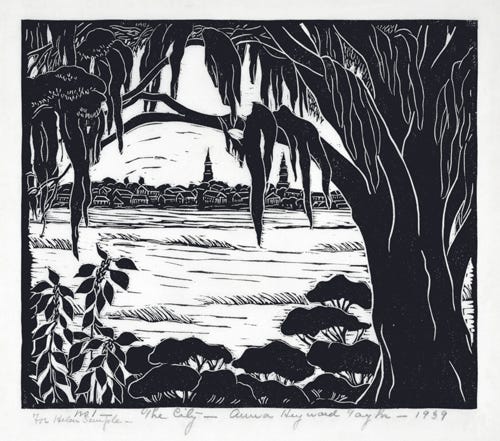

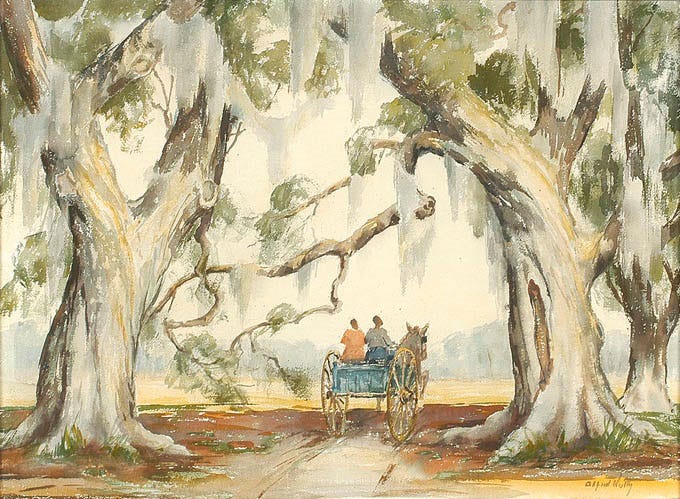

Although there was never an “art colony” per se in Charleston, artists created images that served to attract visitors to the area. Initially, the artwork of Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, Anna Heyward Taylor, and Alfred Hutty (a transplanted northerner) emphasized “picturesque views that veiled the reality of a city that had seen brighter times.”

Black artist Edwin Harleston was largely excluded from the Charleston Renaissance circles of the time, but should be recognized for his artistic contributions as well, which were featured in SC History Newsletter #79 in more detail.

Charleston Renaissance paintings and prints were exhibited in such places as Chicago, Washington, and Philadelphia, broadening the appreciation for the Lowcountry.

Because the watercolors were often small-scale and the prints accessibly priced, many tourists purchased them as souvenirs of their visits.

Ultimately, other artists were enticed to the area, converting Charleston into a “mecca” of sorts for painters and printmakers.

The country gradually became Charleston-conscious, and as a result, tourists began to arrive, especially in the spring, to “America’s Most Historic City.”

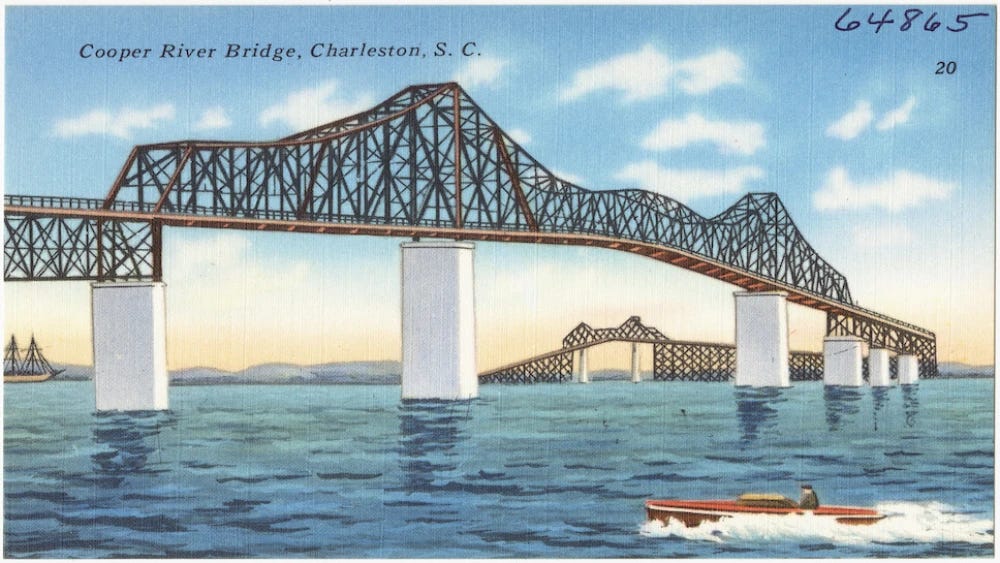

Tourism was enhanced by improved transportation, including the opening of the Cooper River Bridge in 1929, which facilitated automobile traffic with the north and “provided makers of sweet-grass baskets direct access to passing motorists.”

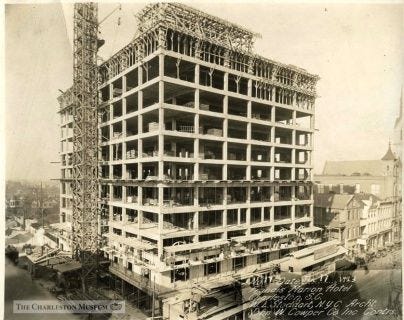

Hotels such as the Francis Marion and the Fort Sumter were built in the early 1920s to accommodate the influx of visitors.

Azalea festivals, musicals, and house and garden tours were offered as entertainment and also served as fund-raisers.

Former plantations, such as Magnolia Gardens and Middleton Place, welcomed tourists to their newly restored gardens.

Most of the new visitors to Charleston were northerners, and many of the wealthier ones purchased derelict area plantations, which they restored.

Among the more notable figures who came to coastal Carolina in the 1930s were Solomon R. Guggenheim, who loaned to the Gibbes Museum of Art his collection of nonobjective painting for its inaugural exhibition (see article below!); Archer M. and Anna Hyatt Huntington, who acquired various Allston family plantations to form Brookgreen Gardens; and Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Kittredge, who transformed the old rice fields at Dean Hall plantation into Cypress Gardens.

Through words, melodies, pictures, and even a dance step named after the city (See SC History Newsletter #78 for a discussion of the origin of the Charleston), the ethos of Charleston was broadcast across the nation.

Although local residents realized that Charleston was undergoing a dramatic revitalization, the phrase “The Charleston Renaissance” did not get widespread usage until the 1980s, although the word “renaissance” occurred occasionally in newspaper accounts.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you know that American businessman and modern art collector Solomon Guggenheim had a passion for the South Carolina Lowcountry?

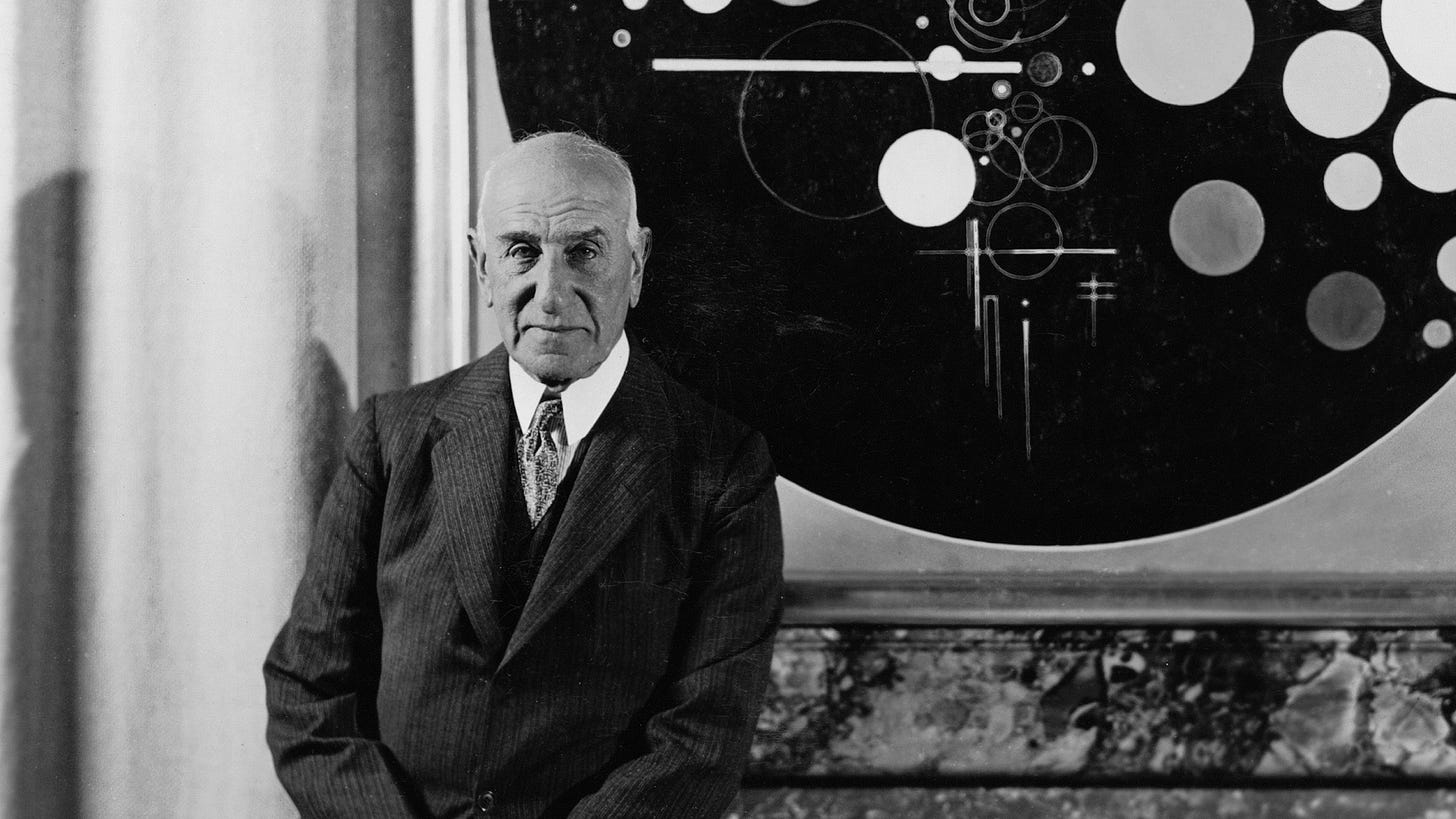

Solomon Guggenheim was an American businessman and art collector, best known for establishing the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

While Guggenheim was passionate about modern art, what many people may not know is that Guggenheim and his wife Irene (of the Rothschild family) were also passionate about Charleston and the Lowcountry.

Solomon and Irene Guggenheim purchased a home on Charleston’s East Battery and also owned a plantation called “Big Survey” located in Yemassee, SC. On the plantation, the Guggenheim’s enjoyed hunting, fishing, riding, “and savoring country life.”

Guggenheim was introduced to the Lowcountry by Bernard Baruch, a family friend and advisor, who owned Hobcaw Barony in Georgetown.

In 1936, Guggenheim connected with the leadership of Charleston’s Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery (now Gibbes Museum) and presented the first formal exhibition of his modern art collection — 21 years before the collection found a permanent home in the renowned museum designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The 1936 exhibition featured works by Marc Chagall, Vasily Kandinsky, and Fernand Leger, among many others. Another exhibition followed in 1938.

Both Guggenheim shows brought international attention to Charleston.

From the exhibition catalogue introduction:

“This exhibition of Mr. Solomon R. Guggenheim's collection is an event of outstanding importance in the history of the Carolina Art Association. Although we are dedicated to the preservation and study of the eighteenth and nineteenth century art of the state, our aim is also to present the art of the present. This exhibition marks our first accomplishment of note toward this objective and we are grateful to Mr. Guggenheim for making it possible.

We are proud of being selected as the first to exhibit this collection and in doing so to present the first comprehensive exhibition of non-objective painting in this country. Charleston was once a leader among communities of cultural achievement and has always been noted for its traditions of culture. It is significant that it now presents an art which looks to the future. There are many cities who might reason that they should have been selected, but the reasons are obvious; there are many collectors who would have been influenced by these reasons and their desire for certain response would have been assured; there are also museums who would have refused the exhibition and been justified by narrow concepts; it is our hope that our future will vindicate an extraordinary collector's vision.

The Baroness Hilla Rebay, who organized the Guggenheim collection, has graciously augmented its exhibition with works from her collection. We are greatly indebted to the Baroness who has given her services as director of the exhibition and compiler of this catalog.

ROBERT N. S. WHITELAW, Director

Carolina Art Association”

Angela Mack, Gibbes Museum executive director, reflected on how the public reacted to the original Guggenheim Non-Objective Art exhibitions in the 1930s, which would have been pretty radical for the time:

“It’s interesting to look at press clippings from that time…There were both very positive and very negative reviews, and it confused some people…America as a whole was becoming more open than ever before.”

After 80 years, in 2016, Guggenheim’s collection returned to the Gibbes in an exhibition called the Realm of the Spirit: Solomon R. Guggenheim Collection and the Gibbes Museum of Art. Some of the original works that Guggenheim exhibited at the Gibbes in 1936 and 1938, returned “in a historic and captivating show.”

Guggenheim’s great-granddaughter wrote in a blog post on the Gibbes website:

“Showing these works in the ’30s in Charleston must have caused quite the chatter around town. It will be interesting to see how it is received in the 21st century, eighty years later. I, for one, am thrilled to have these paintings come home, albeit temporarily, to the Gibbes, where they were given their first exhibition space for the world to see.”

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“The first public exhibition of the Solomon R. Guggenheim collection of non-objective paintings is an outstanding event of lasting importance in the history of art. While thousands of museums and private collections are filled to overflowing with objective works of old masters and new masters, very few shrines of non-objective art can ever exist because non-objective art, being purely creative, is extremely rare, difficult to create, and hard to collect. Although we are living in a period contemporary with its creation those who have realized its importance have difficulty even to-day in finding masterpieces and in choosing wisely. The responsibility for choice is all the more personal and individual because no age-old experience of non-objective art has formed an average standard for selection.

The privilege of discovering a genius while he is alive, of realizing values which will endure and of acknowledging the greatness of a contemporary period is given to very few. These intuitive personalities are so rare that they usually become famous because they advance and help others to advance, proclaiming a new spirit and a new period.

Never before in the history of the world has there been a greater step forward from the materialistic to the spiritual than from objectivity to non-objectivity in painting. Because it is our destiny to be creative and our fate to become spiritual, humanity will come to develop and enjoy greater intuitive power through creations of great art, the glorious masterpieces of non-objectivity."

— Excerpt from Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Director, Hilla Rebay’s introduction for the catalogue for the 1936 Exhibition on the Solomon R. Guggenheim Collection of Non-Objective Paintings on display at the Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery

Charleston Renaissance article sources:

Severens, Martha R. “Charleston Renaissance.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, 15 April 2016, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/charleston-renaissance/#:~:text=The%20Charleston%20Renaissance%20was%20a,that%20reshaped%20the%20city’s%20destiny. Accessed 7 May 2024.

“Spiritual Society Beginnings.” The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, https://gullahspirituals.org/. Accessed 7 May 2024.

Solomon Guggenheim article sources:

Hiester, Becca. “Guggenheim Comes to Charleston, Again - Gibbes Museum of Art.” Gibbes Museum of Art, 14 Oct. 2016, https://www.gibbesmuseum.org/news/guggenheim-comes-charleston/. Accessed 7 May 2024.

“Solomon R. Guggenheim’s Collection Returns to the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston.” The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation, https://www.guggenheim.org/news/gibbes-museum-charleston. Accessed 7 May 2024.

“Solomon R. Guggenheim Collection of Non-Objective Paintings.” Internet Archive, 1936, https://archive.org/details/

solomonrguggenhe00gugg/page/6/mode/2up. Accessed 7 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of today’s newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!