#81: Joel Poinsett, Songs of the Civil War, and Hero Tales from the American Revolution

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Enjoy weekly SC history and upcoming SC historical events

Welcome to the first 100 days of the South Carolina History Newsletter! My name is Kate Fowler and I live in Greenville, SC. I have a 9-5 job in marketing, and outside of work, have a deep love of history. I started this newsletter as a passion project to learn more about our beautiful state and build a community of fellow SC history lovers along the way! To establish a foundation for the newsletter and to grow my expertise on a wide variety of South Carolina historical topics, this past February I challenged myself to post 100 newsletters in 100 days. After this coming May 20th, the newsletter will become weekly. Thank you for joining the journey!

Dear reader,

Welcome to Newsletter #81 of The South Carolina History Newsletter! I’m so happy you’re here.

As always, I’d like to also extend a special welcome to the following new subscribers — woohoo! Thank you for subscribing.

sckatieowens

chickenmcfuggits@gmail.com

jimmy.tuck@gmail.com

judgeneel@me.com

Mwjames@ftc-i.net

nicole_vb17@yahoo.com

rcleveland1960@gmail.com

roostny@gmail.com

jchmura@aol.com

kdover.email@gmail.com

As of today, we have 535 subscribers and 16 paid subscribers — I’m very grateful!

I hope you enjoy today’s newsletter, and as always, please feel free to reply to this email with your ideas and suggestions on South Carolina history topics you’d like to learn more about. I’m only a click away.

Additionally, please join us & keep the conversation going by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here! I can’t wait to meet you.

And now, let’s learn some South Carolina history!

Yours truly,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

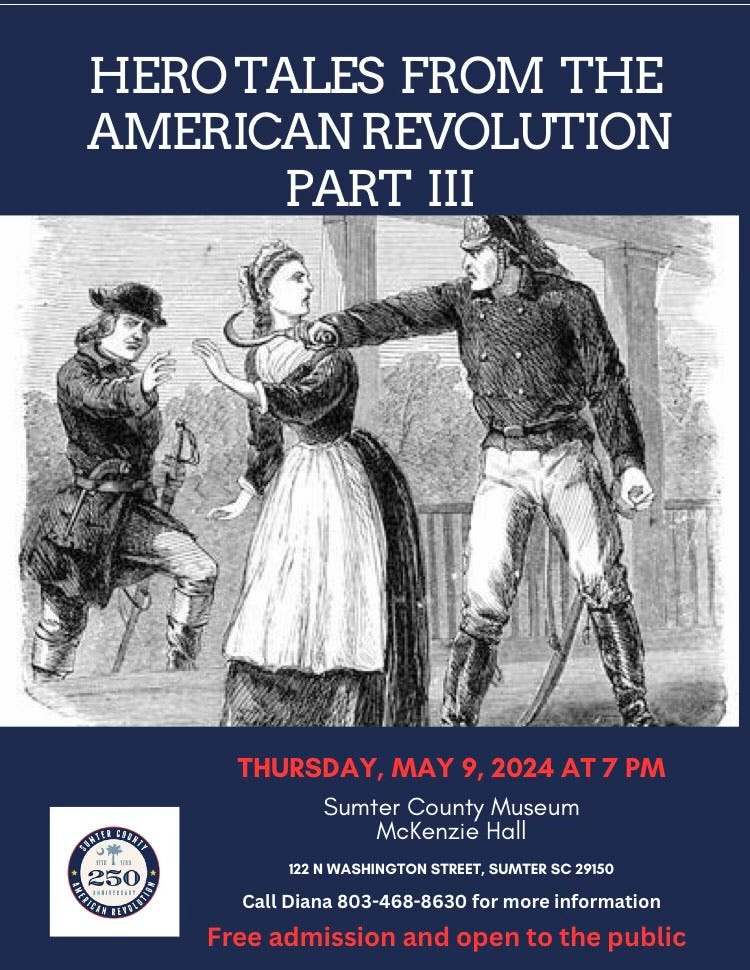

➳ Featured SC History Event

Please enjoy our featured SC History Event below, and click here to visit my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email or send me a note at schistorynewsletter@gmail.com.

Grateful to subscriber Penny Steed for making me aware of the event below!

➳ SC History Fun Facts

I.

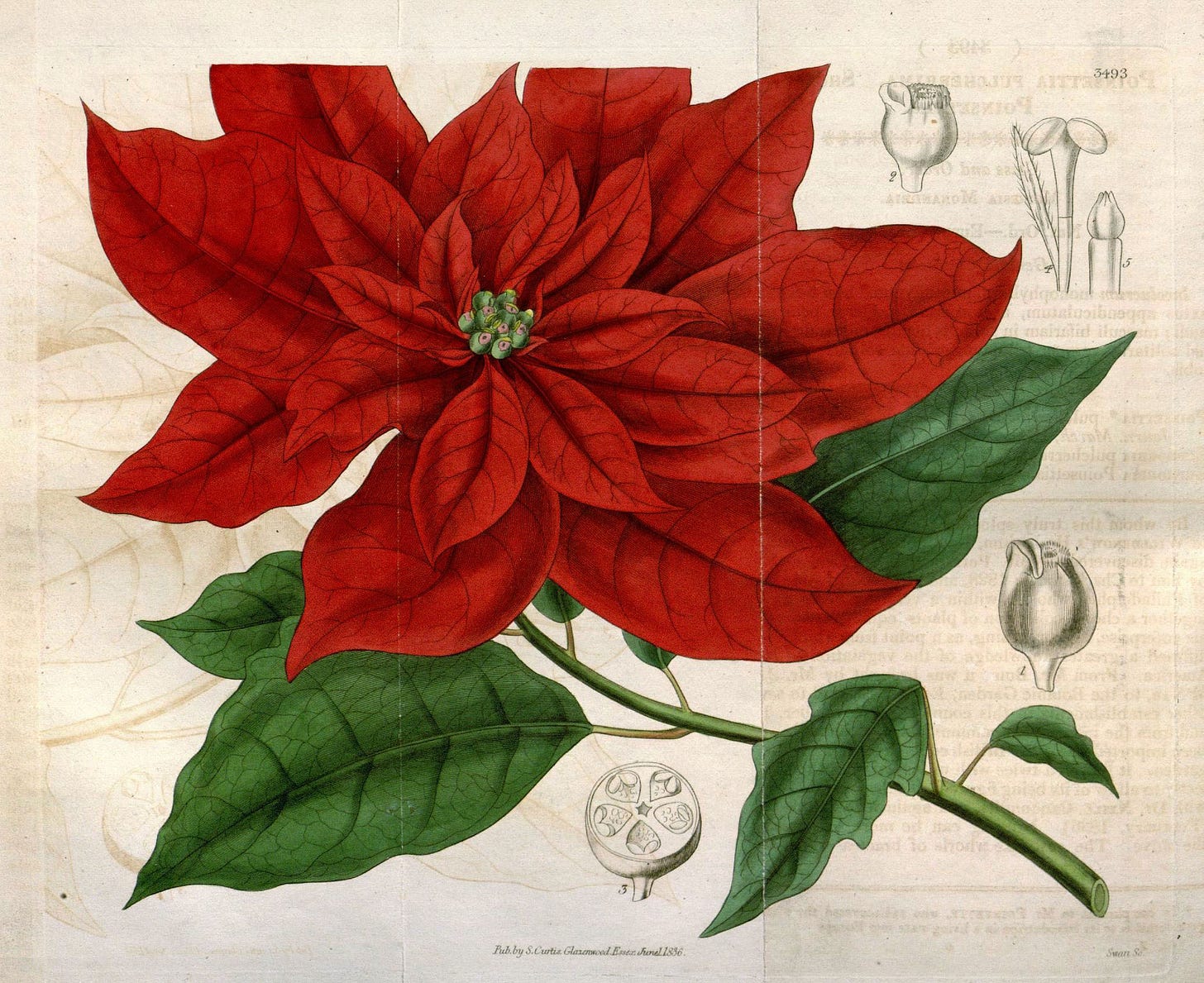

Did you know that famous South Carolinian Joel Poinsett is the namesake for the ubiquitous red plant each holiday season, the poinsettia?

Joel Poinsett was born on March 2, 1779, in Charleston and was the son of the Huguenot physician Elisha Poinsett and his English wife, Ann Roberts.

As a child, Poinsett spent 6 years in England, where his formal education probably began. In 1794 he entered the Greenfield Hill, Connecticut, academy of Dr. Timothy Dwight (who would become the 8th president of Yale University, then called Yale College) but “stayed only two years because of his frail health.”

Returning to England, Poinsett attended private school, where he excelled in languages. In 1797 he began medical school in Edinburgh, Scotland, but remained only one year. Returning to Charleston, Poinsett briefly studied law in 1800, but “his interest quickly waned.”

In 1801 Poinsett set out for Europe, where he would spend most of the next 7 years traveling across the continent. His fluency in foreign languages helped him “form associations with several powerful European leaders, including Napoleon I, the French financier Jacques Necker, and Czar Alexander I of Russia.”

In 1802, Poinsett had many European adventures, including hiking up Mount Etna on the island of Sicily.

In January 1807, Poinsett visited Russia. Levett Harris, consul of the United States at St. Petersburg, and the highest American official in the country, hoped to introduce Poinsett at court to Czar Alexander. Learning that Poinsett was from South Carolina, the Empress asked him if he would inspect the cotton factories under her patronage. Poinsett also dined w/ Czar Alexander. The czar attempted to entice Poinsett into the Russian civil or military service. Poinsett was hesitant, which prompted Alexander to advise him to explore the empire, get to know its people, and then decide. Always interested in travel, Poinsett accepted the invitation and left St. Petersburg in March 1807 on a journey through southern Russia. He was accompanied by his English friend Philip Yorke, Viscount Royston and 8 others. With letters recommending them to the special care of all Russian officials, Poinsett and Royston made their way to Moscow. They were among the last westerners to see Moscow before its burning in October 1812 by Napoleon's forces.

Poinsett returned home in 1808 as war between Britain and the United States loomed. He hoped to secure a military appointment but instead in 1810 was named U.S. trade envoy to South America, where British forces regarded him as a “suspicious character.”

From SC Encyclopedia about Poinsett’s “suspicious” activities in South America:

“An ardent republican who long wanted a military career, Poinsett was soon promoting rebellion among South American countries. Failing to persuade Buenos Aires to break with Spain, in 1811 he crossed the Andes to Chile. Despite Washington’s neutrality, Poinsett urged Chile to rebel and helped organize an army. But by 1814 Royalists had crushed the rebellion, and he was forced to flee.”

Returning to South Carolina, Poinsett was elected in 1816 to the General Assembly, where he became a strong advocate of internal improvements.

In 1819 Poinsett became president of the state Board of Public Works, actively supervising canals and roads built to link Charleston with the undeveloped interior, including a road through the Saluda Gap that brought trade from North Carolina and Tennessee.

The oldest bridge in South Carolina is named for Joel Poinsett and today is a popular tourist attraction. It was built in 1820 as part of a road from Columbia, SC to Saluda Mountain. It is part of a 120-acre Poinsett Bridge Heritage Preserve.

In 1821 Poinsett won a seat in Congress, where he represented the Charleston congressional district until 1825. Although he seldom participated in floor debates, Poinsett “opposed tariff increases, supported expansion of the military, and favored recognition of South American republics.”

In 1825 President James Monroe appointed Poinsett as the first U.S. ambassador to Mexico. Britain’s influence there was strong, and Poinsett urged independence from Europe under America’s Monroe Doctrine.

Poinsett tried unsuccessfully to purchase Texas for the United States, thereby antagonizing Mexico.

He failed to win a commercial treaty but succeeded in promoting trade along America’s southwestern border. His “meddling” in local political affairs made him unpopular in Mexico, especially among British commercial interests and the country’s monarchists. The Mexican government requested his recall, and Poinsett left the country in January 1830.

Poinsett returned to South Carolina at the height of the nullification crisis and eventually became one of the state’s leading Unionists, even serving as “President Andrew Jackson’s confidential local agent in opposing the nullifiers and secretly organizing Unionist militias.”

It is a strange paradox that Poinsett was a Unionist, as he himself owned slaves. (Note from Kate: in fact, Civil Rights leader and South Carolinian Septima Poinsette (yes extra “e”) Clark’s father Peter Poinsette was a slave owned by Joel Poinsett — and tomorrow’s newsletter will discuss this more!)

Poinsett’s efforts were praised in the North, but his influence in South Carolina waned before the states’ rights doctrine put forth by his “political nemesis,” John C. Calhoun.

After the crisis ended, on October 24, 1833, Poinsett married Mary Izard Pringle, the widow of a wealthy rice planter. The couple had no children.

In 1837 President Martin Van Buren named Poinsett secretary of war. He quickly set out to improve and expand the nation’s “paltry army of 8,000 poorly trained soldiers.”

He raised standards and sent officers to Europe for instruction.

His artillery improvements made him “one of America’s foremost 19th-century military reformers.” In 1838 Congress enlarged the army to 12,577 men.

As secretary, Poinsett also “presided over removal of more Indians from east of the Mississippi than any other of his predecessors.” In an 1841 report, Poinsett said that 40,000 Indians had been pushed west of the Mississippi.

He also encouraged exploration, authorizing the western expedition of John C. Fremont and Jean Nicollet as well as the Pacific voyages of Charles Wilkes.

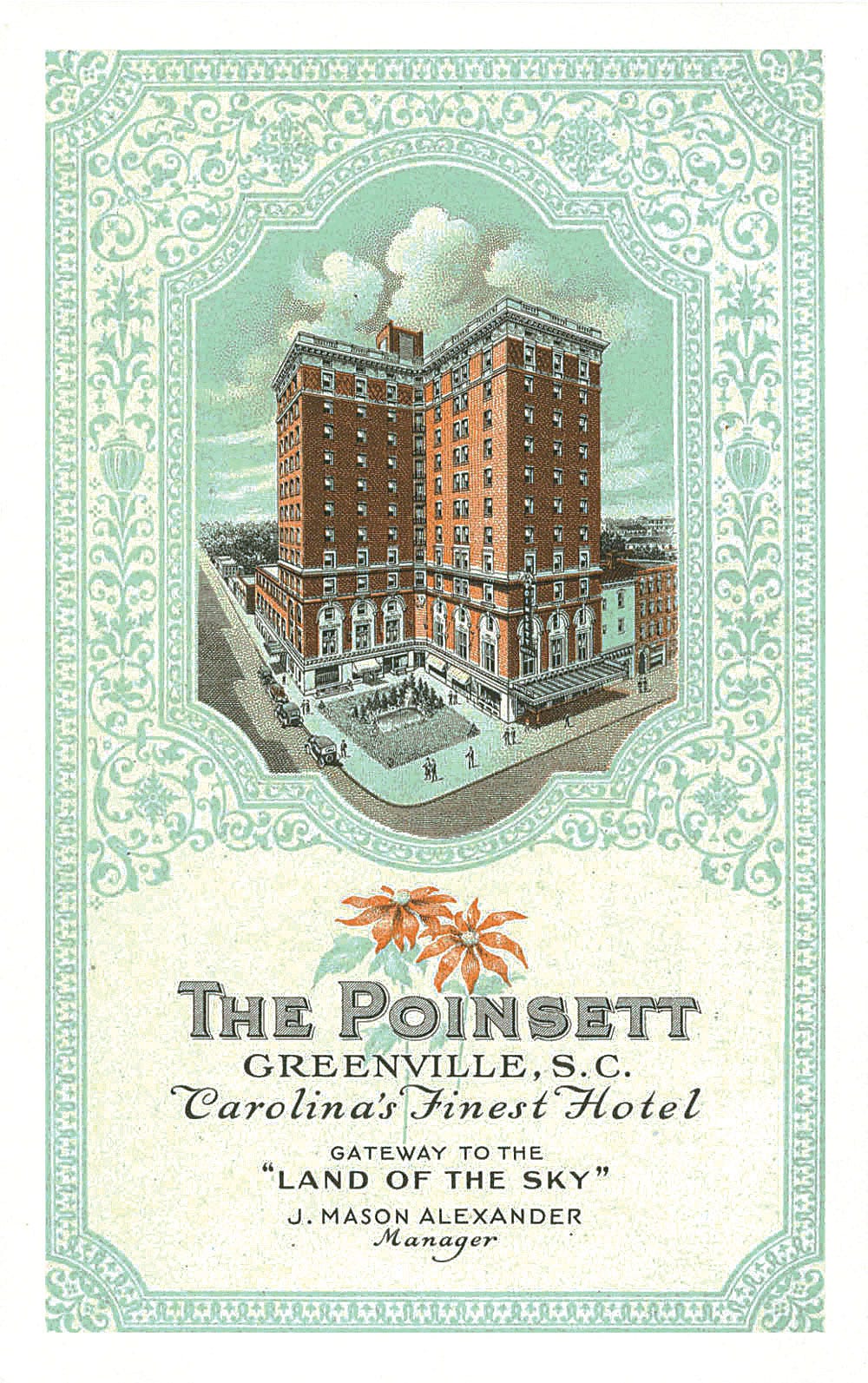

Leaving office in March 1841, Poinsett spent his last decade on his Greenville District farm and his wife’s Santee plantation near Georgetown.

In retirement, he promoted education, economic development, and “weaning of southern life from slavery.”

In 1844 Poinsett was elected president of the National Institute, a forerunner of the Smithsonian Institution. He served on the board of visitors of South Carolina College. He studied animal husbandry, agriculture, and botany.

A red-leafed plant he introduced from Mexico, the poinsettia, was named in his honor.

When secession again threatened the nation in 1850, Poinsett’s friends sought his leadership in opposing the movement, but he declined.

Poinsett died of tuberculosis and pneumonia in Stateburg, SC on December 12, 1851, while traveling from Charleston to his Greenville home. He was buried in the cemetery of the Church of the Holy Cross, Stateburg.

There is a state of Joel Poinsett in the heart of downtown Greenville, SC in front of the hotel named after him as well, the Westin Poinsett Hotel!

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my source for this section

Please leave a comment below!

II.

Did you know the Civil War was a very musical war?

(Note from Kate: I was inspired to learn more about the music of the Civil War after SC History Newsletter #57 where we discussed how the Union army song “John Brown’s Body” that was sung on the first Memorial Day in Charleston on May 1, 1865. I was also intrigued by my research in SC History Newsletter #77 on the Rebel Yell and the Confederate song “Dixie.” Let’s listen to what the Union music and Confederate music sounded like during the Civil War.)

In his book Lincoln and the Music of the Civil War, author Kenneth A. Bernard calls the Civil War “a musical war.”

In the years preceding the conflict, Bernard points out “that singing schools and musical institutes operated in many parts of the country. Band concerts were popular forms of entertainment and pianos graced the parlors of many homes. Sales of sheet music were immensely profitable for music publishing houses on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line.”

Thus, when soldiers North and South marched off to war, they took with them a love of song that “transcended the political and philosophical divide between them.”

Music passed the time; it entertained and comforted; it brought back memories of home and family; it strengthened the bonds between comrades and helped to forge new ones.

And, in the case of the Confederacy, it helped create the “sense of national identity and unity.”

Bernard writes:

"In camp and hospital they sang — sentimental songs and ballads, comic songs and patriotic numbers....The songs were better than rations or medicine...during the first year [of the war] alone, an estimated two thousand compositions were produced, and by the end of the war more music had been created, played, and sung than during all our other wars combined. More of the music of the era has endured than from any other period in our history."

Music was played on the march, in camp, even in battle; armies marched to the heroic rhythms of drums and often of brass bands.

The fear and tedium of sieges was eased by “nightly band concerts, which often featured requests shouted from both sides of the lines.”

Around camp there was usually a fiddler or guitarist or banjo player at work, and voices to sing the favorite songs of the era.

In fact, Confederate General Robert E. Lee once remarked, “I don’t believe we can have an army without music.”

The Union army’s anthem was the "The Battle Hymn of the Republic” which had been adapted by American author and poet, Julia Ward Howe from the song “John Brown’s Body.” Other Union songs included "Battle Cry of Freedom," "May God Save the Union," and “Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!” Let’s take a listen.

Union Anthem: “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”

Union Song: “Battle Cry of Freedom”

Union Song: “May God Save the Union”

The song “Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!” was also one of the most popular songs of the Civil War. George F. Root wrote both the words and music and published it in 1864 “to give hope to the Union prisoners of war.” The song is written from the prisoner's point of view. The chorus tells his fellow prisoners that hope is coming. Let’s listen below.

Union Song: “Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!”

The South’s anthem of the Confederacy was “I Wish I Was in Dixie” or just “Dixie.” Other songs of the Southern army were: "God Save the South," "God Will Defend the Right," and "The Rebel Soldier". Let’s listen below.

Confederate Song: “I Wish I Was in Dixie”

Confederate Song: “God Save The South”

Confederate Song: “God Will Defend the Right”

Confederate Song: "The Rebel Soldier"

“The Bonnie Blue Flag,” another pro-Southern song was so popular in the Confederacy that Union General Benjamin Butler “destroyed all the printed copies he could find, jailed the publisher, and threatened to fine anyone—even a child—caught singing the song or whistling the melody.”

Confederate Song: "The Bonnie Blue Flag"

After Robert E. Lee surrendered, Abraham Lincoln, on one of the last days of his life, asked a Northern band to play “Dixie” saying it had always been one of his favorite tunes. A symbolic moment indeed.

Please scroll to the bottom of this email for my sources for this section

Please leave a comment below!

➳ Quote from an SC historical figure

“I wish I was in the land of cotton,

Old times they are not forgotten;

Look away! Look away! Look away! Dixie Land.

In Dixie Land where I was born,

Early on one frosty mornin,

Look away! Look away! Look away! Dixie Land.

CHORUS:

Then I wish I was in Dixie, hooray! hooray!

In Dixie Land I’ll take my stand to live and die in Dixie,

Away, away, away down South in Dixie,

Away, away, away down South in Dixie.”

—Excerpt from the Confederacy’s anthem “Dixie”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of His terrible swift sword

His truth is marching on

Glory, Glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on”

—Excerpt from the Union’s anthem “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”

Joel Poinsett article sources:

Chandler, Charles Lyon; Smith, R. (1935). "The Life of Joel Roberts Poinsett". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 59 (1): 1–31. JSTOR 20086886.

Hammond, James T. “Poinsett, Joel Roberts.” South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/poinsett-joel-roberts/. Accessed 1 May 2024.

Songs of the Civil War article sources:

“Music of the 1860’s | American Battlefield Trust.” American Battlefield Trust, 15 Dec. 2008, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/music-1860s. Accessed 1 May 2024.

I always want to improve my work. Answer the poll below to give me your review of this newsletter. I also welcome your suggestions for new content! Simply reply to this email with your ideas. Thank you!

Where was Poinsetts Greenville home that is pictured in this article?