#149: Galloping Through History: Charleston’s Racing Roots + Carolina Day at Fort Moultrie

For South Carolina history lovers far and wide! Published weekly on Monday mornings. Enjoy weekly SC history articles, upcoming SC historical events, and other South Carolina recommendations.

Dear readers,

It’s beginning to feel more and more like summer and I hope everyone is enjoying the warmer weather and maybe has some plans for the lake or the beach coming up soon. :)

As the days get hotter, I wanted to quickly highlight our wonderful SC History Newsletter sponsor, Oliver Pluff & Co., who can supply you with a cold and refreshing Oliver Pluff Southern Style Iced Tea, among many other delicious libations. Yummm!

I really enjoyed diving into Charleston’s horse racing history for this week’s history topic. The next time I venture to Charleston, I am excited to walk in Hampton Park on the grounds that once were the famed Washington Course, the epicenter of South Carolina’s elite social scene — every February for Race Week.

Sincerely,

Kate

(Writing from Greenville, SC)

Support the SC History Newsletter by considering heritages teas (inspired by South Carolina and American history!) from our fantastic sponsor Oliver Pluff & Co. — click on their beautiful ad below! :)

➳ Housekeeping for new subscribers!

New friends! There are over 100 previous SC History newsletters on topics ranging from the founding of Charleston, sunken Confederate submarines, railroad tunnels filled with blue cheese, and more! See our archive here!

Send me your comments or topic ideas: I love it when subscribers write to me! Have a SC History topic or question you’d like for me to write about? Have additional ideas or feedback? Just reply to this email and let me know!

Join us on social: Keep the conversation going and join over 100 other subscribers by becoming a member of our SC History Newsletter Facebook Community here!

If your email “cuts off”: In your email app or website, if my emails “cut off” for you, please click the title of the email and it will take you to the full post on the Substack. I don’t want you to miss any content!

Love the SC History Newsletter? Please click the button below to share with a friend!

➳ Featured Upcoming SC History Events

🗓️ Saturday, June 28th, 10:00 am - 6:00 pm

📝 Carolina Day at Fort Moultrie

📍Sullivan’s Island, SC

💻 Website

From the event website:

“Mark your calendars for Carolina Day at Fort Moultrie! Step back in time for a FREE full day of hands-on history, family fun, and live reenactments! Expect cannon fire 💥 cricket lessons 🏏 indigo dyeing 💙 musket firings 🎯 art activities 🎨 book signings 📚 and a whole lot more. From colonial encampments and archaeology digs to food trucks and kids’ games — this celebration brings the 1700s to life right on the island we call home.”

➳ 🗓️ Paid subscribers get access to my SC History Events Calendar that organizes all the upcoming SC history events I have discovered. Please let me know if you’d like to add an event to the calendar! Reply to this email to send me your events.

➳ Revisit Spring/Summer Topics From The Archive:

Thought I would re-post these newsletter below as the weather turns warmer - these were fun to write and really interesting history!

#104: History of staying cool in SC, The Battle of Huck’s Defeat, and The Slave Dwelling Project

#105: Coca-Cola in SC, Camden Parlor Talk, and Southern Ladies' Civil War and Antebellum Fashions

➳ Galloping Through History: Charleston’s Racing Roots

Horse culture, and horse racing, have long been a part of South Carolina’s history and heritage. Today, South Carolinians can enjoy many exciting races each year, including the Carolina Club (annually in March in Camden), the Colonial Cup (annually in November in Camden), the Aiken Fall Steeplechase (annually in November in Aiken), and Steeplechase of Charleston (annually in November in Hollywood, SC).

But where did the horse racing tradition begin? Horse racing was a favorite sport in England since the 16th century. When British colonists came to America, the horse racing tradition followed them to the New World.

The earliest record of horse racing in South Carolina can be found in the South-Carolina Gazette in February of 1734.

Over the next 20 years after this first newspaper article, horse racing gained in popularity in the colony and became officially organized when a group of Lowcountry gentleman founded the South Carolina Jockey Club in 1758.

The South Carolina Jockey Club developed “Race Week” which, by the 1770s, became the most important social season of the year for elite South Carolinians.

However, what enormous, earth-shattering event also happened in the 1770s? You guessed it, the Revolutionary War halted the events of the South Carolina Jockey Club and Club operations paused during the war. Though it feels important to acknowledge that while the beautiful horses of this time period may not have been racing on the track, they were racing to stay alive on the battlefield — with their owners.

In December of 1783, one year after the British evacuated Charleston, the South Carolina Jockey Club re-commenced its operations, and its membership surged. However, due to economic hardships in the post-war period, the club had to disband in 1788, but was reestablished in 1791.

At the turn of the 19th century, the South Carolina Jockey Club ushered in what would be called the “Golden Age of Racing” in the state.

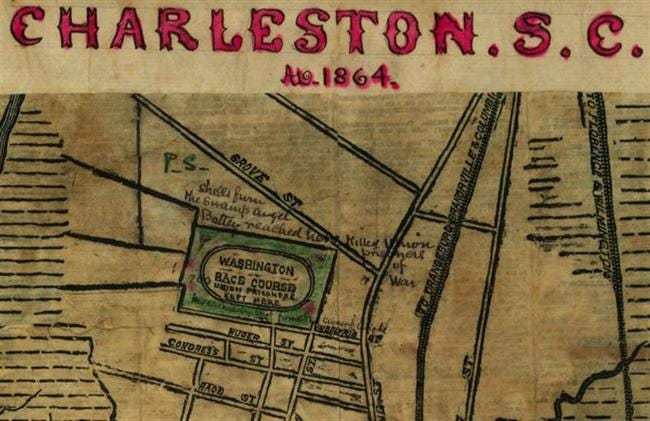

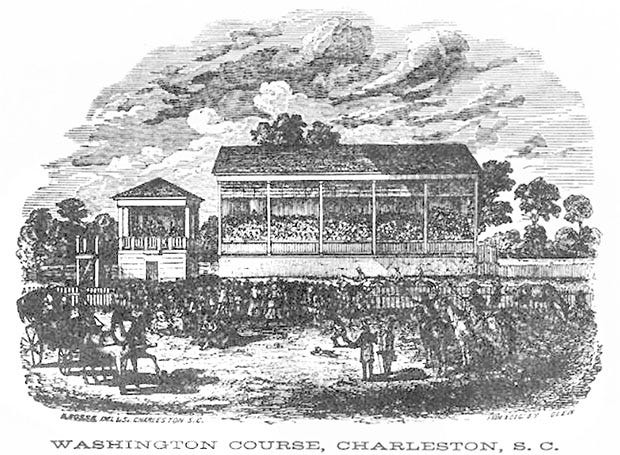

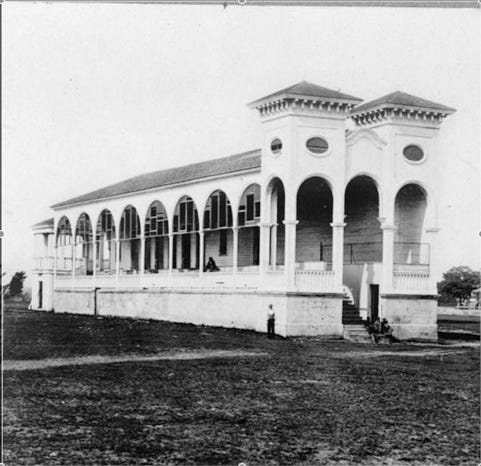

Race Week was held specifically at the famed Washington Course, a 1-mile loop around today’s Hampton Park in Charleston. The track was built on land formerly part of Robert Gibbes’ Orange Grove Plantation.

The Washington Course was a business venture of some of most prominent men in the state, many whose names you will likely recognize from the annals of history: including William Alston, William Washington, Wade Hampton, Charles Coatsworth Pinckney, Robert Gibbs, Henry Middleton Rutledge, Gabriel Manigault, William Moultrie and 11 other breeders of thoroughbred racehorses.

While there were other racecourses in Charleston, from its first race on February 15, 1792, The Washington Course was “home to the crème de la crème of the South’s racing elite.”

The club’s annual races, which took place in February each year, were the highlight of the Charleston social season. These races also served as “a common meeting place for members of the planter class from across the state.”

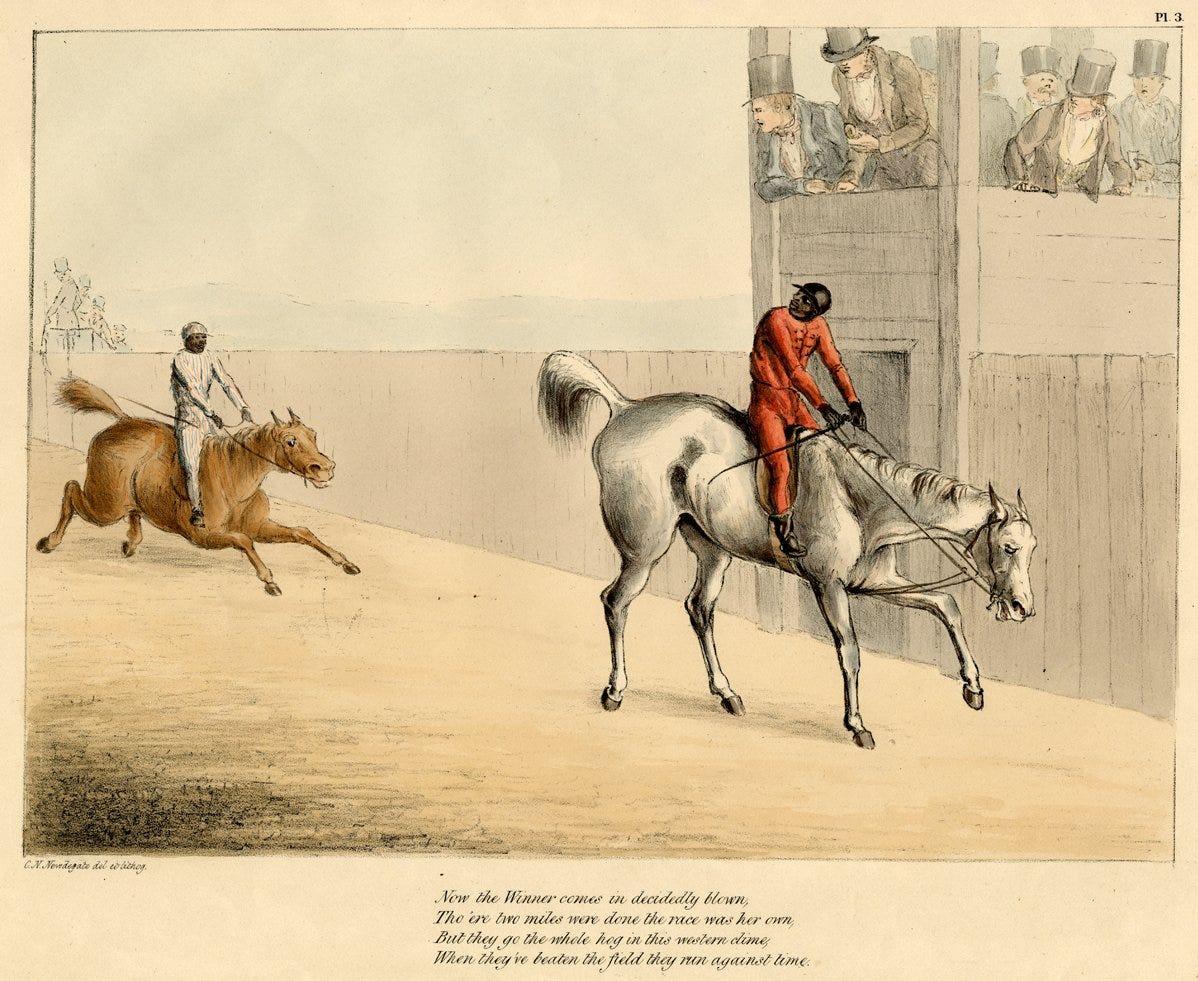

The same dynamics of plantation life also fed into horse racing, where enslaved Africans played their role as servants to families traveling to and from Charleston, and perhaps most visibly — (not all but) most horse racing jockeys were enslaved men.

In a traveling art exhibition from 2019 called A Brief History of Black Horsemen in Racing, the Clarice & Robert H. Smith Educator, Valerie Peacock wrote about the following amazing sketches and what they reveal about Race Week at the Washington Course in Charleston.

Ms. Peacock writes:

“The earliest item that we found is a series of three lithographs dated 1840, depicting a race at the Washington Race Course in Charleston, South Carolina…These were authored by British conservative political Charles Newdigate Newdegate and seem intended to mock the American horse racing community. This item also exemplifies that some of America’s earliest and prolific jockeys were enslaved men.”

I find the sketches above and below fascinating and hauntingly beautiful.

The poem at the bottom of Plate 1 above reads:

“At tap of the drum they jump off from the stand,

Be the track dry or wet as heavy with sand,

At a pace which at once makes fast ones extend,

And e'en the best mounted cry bellows to mend.”

And here is the poem on the bottom of Plate 3 above:

“Now the Winner comes in decidedly blown,

Tho’ ere two miles were done the race was her own,

But they go the whole hog in this western clime

When they’ve beaten the field they run against time.”

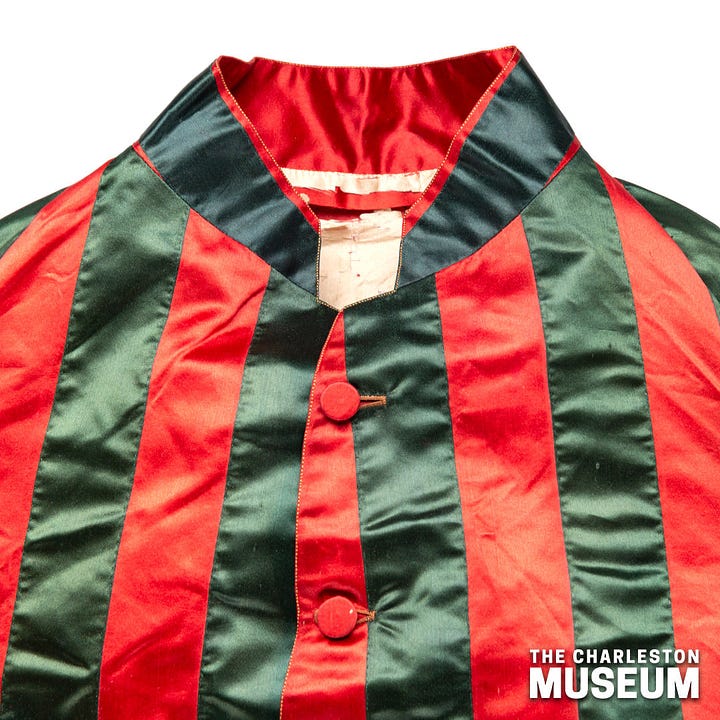

One of the Washington Course’s founders had a grandson named J. Motte Alston (1821-1901) who wrote about what the Alston family slaves would wear during Race Week: “House servants wore dark green broadcloth coats trimmed with silver braid and red facings and green plush trousers.”

While the lithograph below, housed in the Yale University Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, is set in Cuba in the 1840s, not Charleston, I wanted to share it here as it depicts a horse-drawn carriage (a quitrin), chauffeured by a black, enslaved coachman wearing the sort of decorative livery described during Charleston’s Race Week above.

J. Motte Alston also recounted tales of Thomas Turner, the Alston family’s slave and prize jockey:

“Thomas Turner was a great favorite and was indulged and respected. He was my grandfather’s most trusted race-rider – when he owned a number of famous horses… horseracing was confined to gentlemen, and not gamblers, and was a pastime and not a profession. There were Gallatin, Shark, Comet, Black Maria, Symmetry and many others.”

Alston further described how in the summer, horse racers met in Virginia and in the winter at Charleston, Columbia, Camden, etc.

Here is a description from the CharlestonRaconteurs.com of what Race Week was like in Charleston and gives an overview of the social scene:

“After the Washington Course was completed, the club’s annual Race Week, held each February, marked the pinnacle of Charleston’s social season. Here the great Lowcountry planters gathered to show their horses, make bets, attend a few balls, seal a few business deals, drink fine Madeira wine, and introduce their daughters to the right sort of people in the reserved seating section. Race Week was, as Jockey Club historian John Beaufain Irving described it in 1857, the "carnival of the state."

Another Alston family member, Mrs. Emma Pringle Alston, left a record for the Race Week Ball of 1851:

“There is no wine list but were six dozen wineglasses and all the champagne glasses “as could be collected.” Eighteen dozen plates, fourteen dozen knives and twenty-eight dozen spoons were needed for the consumption of four wild turkeys, four hams, sixty partridges, six pair of pheasants, six pair of canvasback ducks, five pair of wild ducks, and ten quarts of oysters. There were also four pyramids (two crystallized fruit, two of coconut) four orange baskets, seven dozen Kiss cakes, seven dozen macaroons, eight Charlotte Russes, four Italian creams, four chocolate cakes, four ‘small black ones’ and ‘an immense quantity of bonbons’. Coffee for those who wished it and ‘three dollars’ worth of celery and lettuce completed the menu.”

William T. Porter, a well-known newspaperman and secretary of the New York Jockey Club in the mid-1840s wrote with admiration about Charleston’s racing society:

“The Charleston races are the most popular, the most fashionable and the best attended of any in the United States. Race week, in that city, has been aptly termed ‘the Carnival’ of South Carolina—the annual jubilee of the State. The reason is perfectly obvious; the course and its appointments are under the control of gentlemen of the highest character, and nothing is permitted to interfere with the legitimate sports of the Turf, which are managed with a degree of spirit, liberality, and scrupulous propriety unknown elsewhere on this side of the Atlantic.”

As these races gained popularity, they attracted spectators and horse breeders from other states as well.

There were grandstands built for VIPs and other spectators, and there was even a women’s-only grandstand.

According to Historic Charleston, the spirit of the week was akin to a modern-day Mardi Gras atmosphere for the elites, while pressures mounted for the slave population, both the domestic workers and jockeys:

“The atmosphere of Race Week amongst the elite was one of jovial recreation; foreign visitors were granted access to the races for free, balls and banquets were held, and the Charleston truly took on an ethos akin to today’s Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans. To get the complete story, however, one must remember that for every added leisure activity belonging to the wealthy, there was added tasking and responsibility, and less rest, for the enslaved of the city. Schools and businesses were closed, which meant that houses were full of people requiring service all day long, and the enslaved were expected to pick up additional duties in order to make the week run smoothly. In addition, the attention that would be turned to grooms, farriers, carriage drivers, and footmen as they cared for horses would increase. Enslaved jockeys would be put under similar scrutiny, and they would experience immense pressure from those who enslaved them to win their races. The pressure to succeed likely grew in proportion to the increasing sizes of trophies and purses as the 19th century wore on.”

The Washington Course had strict rules. No rider “shall presume to cross, jostle, strike, or use any foul play whatever.” If they committed any of these infractions, they were banned from racing again.

Furthermore, jockeys had a strict dress code: “Riding Waistcoat, Leather Breeches, Leather Boots, or half Boots & a Jockey Cap of Silk or Velvet.”

Below, see an extraordinary jockey uniform owned by Colonel William Alston, whose grandson J. Motte Alston above wrote about their enslaved coachman and jockey, Thomas Turner. This uniform was made for Colonel Alston himself, but Thomas Turner, the enslaved jockey would have worn a similar ensemble when riding. The deep green and red stripes were the livery colors of Clifton and Fairfield plantations in Waccamaw, South Carolina — owned by the Alston family.

The Golden Age of Racing was soon to come to an end. The 1861 Race Week heat was won by a horse named Albine, owned by a man named John Cantey. Thereafter, yet another catastrophic war began: The Civil War.

The Washington Course was transformed from a place of parties and privilege to a place of death. The Washington Course would become a location used by the Confederacy to house Union prisoners of war.

Union officers were quartered in the Ladies Club, once the site of Charleston’s most gracious social affairs. Conditions in the open-air camp “were horrendous; 257 Union soldiers’ deaths were recorded. They were buried within and around the racecourse in unmarked graves.”

The Washington Course would play yet another important role. At the end of the Civil War, for those of you who read SC History Newsletter #147, you will recall that what may have been the first-ever recorded Memorial Day, was organized at the Washington Course by emancipated slaves who marched to honor the Union dead — on May 1, 1865. Read more here!

The Golden Age of Racing in Charleston was forever impacted by the violence and economic upheaval of the Civil War.

Per the South Carolina Encyclopedia, “the loss of thoroughbreds during the Civil War and the economic decline that followed led to the demise of horse racing in the state.”

The South Carolina Jockey Club tried to revive itself in the 1870s. In 1875, the club had 100 paying members and though “money was tight,” the club still had a few assets: the track itself and a “large cache of valuable Madeira wine that had miraculously escaped discovery by Union troops. Proceeds from the Madeira’s sale helped refurbish the racecourse.”

Though the fact still remained that horse racing was a “rich man’s sport” and after the Civil War, many had lost their fortunes. Attendance continued to decline. The last race at the Washington Course was in 1882, and thereafter the Jockey Club leased the racecourse, the surrounding pastures, and stables to a local farmer.

With about “2 dozen members left,” the South Carolina Jockey Club disbanded officially on December 28, 1899. Its assets were donated to the Charleston Library Society.”

In 1900, the Library Society rented the land that was formerly the Washington Course to the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition and later sold it to the city of Charleston.

The footprint of the mile-long Washington Course track still exists today! It has been renamed “Mary Murray Drive” and is a favorite pathway of local runners, joggers, and dog walkers in Hampton Park in Charleston.

If you voted just “OK” on the newsletter today, I want to hear from you! Reply to this email and send me your feedback. :)

➳ Sources — Galloping Through History: Charleston’s Racing Roots

"Black Horsemen: From the Library Collection." NSLM Blog, 24 Sept. 2019, https://nslmblog.wordpress.com/2019/09/24/black-horsemen-from-the-library-collection/. Accessed 7 June 2025.

"Charleston’s Washington Race Course." Charleston Raconteurs, https://www.charlestonraconteurs.com/washington-race-course.html. Accessed 8 June 2025.

"Harborside History: Episode 2 – Race Week." Historic Charleston Foundation, https://www.historiccharleston.org/news/harborside-history-episode-2-race-week. Accessed 7 June 2025.

"Off to the Races." Charleston Living Magazine, https://charlestonlivingmag.com/off-to-the-races. Accessed 8 June 2025.

"South Carolina Jockey Club." South Carolina Encyclopedia, https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/south-carolina-jockey-club/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 7 June 2025.

"Washington Race Course." AUSA Coastal South Carolina Chapter Blog, https://www.ausa.org/coastal-south-carolina-chapter/blog/washington-race-course. Accessed 8 June 2025.

"Washington Race Course and Cemetery." The Halsey Map Project, http://www.halseymap.com/flash/window.asp?HMID=29. Accessed 7 June 2025.

“Washington Race Course.” Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/story.php/?story_fbid=10159192178337002&id=16059472001. Accessed 8 June 2025.